Manuel's Tavern on N. Highland Ave.

On December 7, Brian Maloof, owner of Manuel’s Tavern, spoke to Atlanta Studies in the North Ave. Room of his own establishment about the future of his “quintessential neighborhood bar,” which will temporarily close on December 27 for renovations, the first of such since Brian’s father, Dekalb County politician Manuel Maloof, bought and transformed Harry’s Delicatessen with a $4,500 down payment back in 1956. His talk was mostly informational: parking (losing some spaces), seating (a few tables will disappear inside, but the tavern’s gaining outside seating), handicap accessibility (at last), building code compliance (again, at last, and somehow they always got a pass), goodbye to any unsentimental commercial décor (wood paneling, memorabilia, and, of course, the century-old wooden bar top from his grandfather Gibran Mansour Maloof’s erstwhile Tip Top Billiard Parlor stay), the rooftop chickens will be on a “romantic getaway” but will return, and—what everyone was dying to know—fingers crossed it will reopen in time for the 2016 elections and the tavern's 60th birthday next year.

As Brian waxed nostalgic about his father and grandfather and their respective businesses, the Tip Top and Manuel’s, my mind traveled back to over a century ago when the Maloof’s and hundreds of other Syrian families came to Atlanta (and America in general). “But I thought the Maloofs were Lebanese?” you might ask. Indeed they are, and were then ethnically Lebanese, but as Lebanon didn’t become an independently recognized country until 1943, during the great wave of late 19th Century and early 20th Century Arab immigration to the U.S, the area from which they hailed, and as countless arrival documents attest, was then referred to as Greater Syria, or the Syrian Arab Republic, and was controlled by the Turkish Ottoman Empire until the French took over from 1920-1943. Lebanon has indeed been on the map since the Tigris met the Euphrates, its history long and tumultuous, and its freedom hard-won. And just as today you might meet a Serbian who’s tempted to say he is still Yugoslavian, even though his hometown of Kosovo no longer exists, or an African refugee who’s strident about being from Eritrea, NOT Ethiopia (the two countries were an uncomfortable federation from 1947-1993, and hostilities continue), it's not surprising that many of yesterday's “Syrians” prefer to identify as Lebanese (or Palestinian, if they were in fact among the hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees that that later poured into Lebanon around 1947-1948, when the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was adopted and the state of Israel was declared).

The excellent and newly timely 2009 book “Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora” by Sarah Gualtieri explains that “Syrian immigrants to the United States were not a unified group but representatives of various regional, local, and religious identities. They could be at once Ottomans, Syrians, Zahalnis (residents of Zahle), Druze, and Maronites; Damascene Sunnis, Greek Orthodox from Beirut, Jews from Aleppo, and many other combinations. They were men, women, and children who could claim they had little in common yet—because they were immigrants—everything. Recognition of solidarity in the face of difference most often began on the journey to the United States, when Syrians, cramped on slippery ship decks, listened for the sounds of their native language.”

The excellent and newly timely 2009 book “Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora” by Sarah Gualtieri explains that “Syrian immigrants to the United States were not a unified group but representatives of various regional, local, and religious identities. They could be at once Ottomans, Syrians, Zahalnis (residents of Zahle), Druze, and Maronites; Damascene Sunnis, Greek Orthodox from Beirut, Jews from Aleppo, and many other combinations. They were men, women, and children who could claim they had little in common yet—because they were immigrants—everything. Recognition of solidarity in the face of difference most often began on the journey to the United States, when Syrians, cramped on slippery ship decks, listened for the sounds of their native language.”

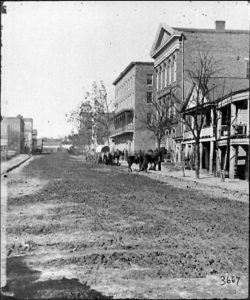

Decatur Street 1864

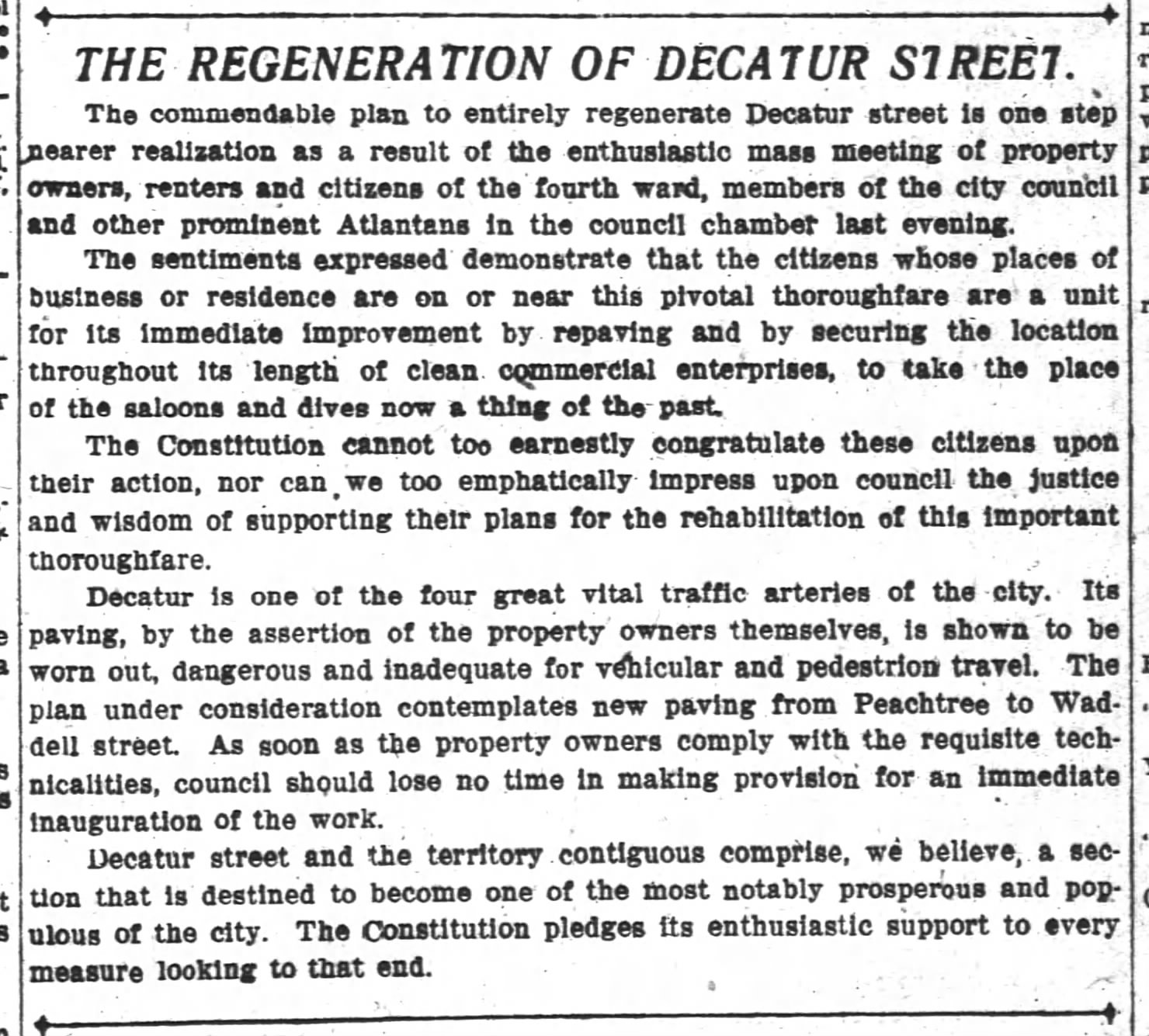

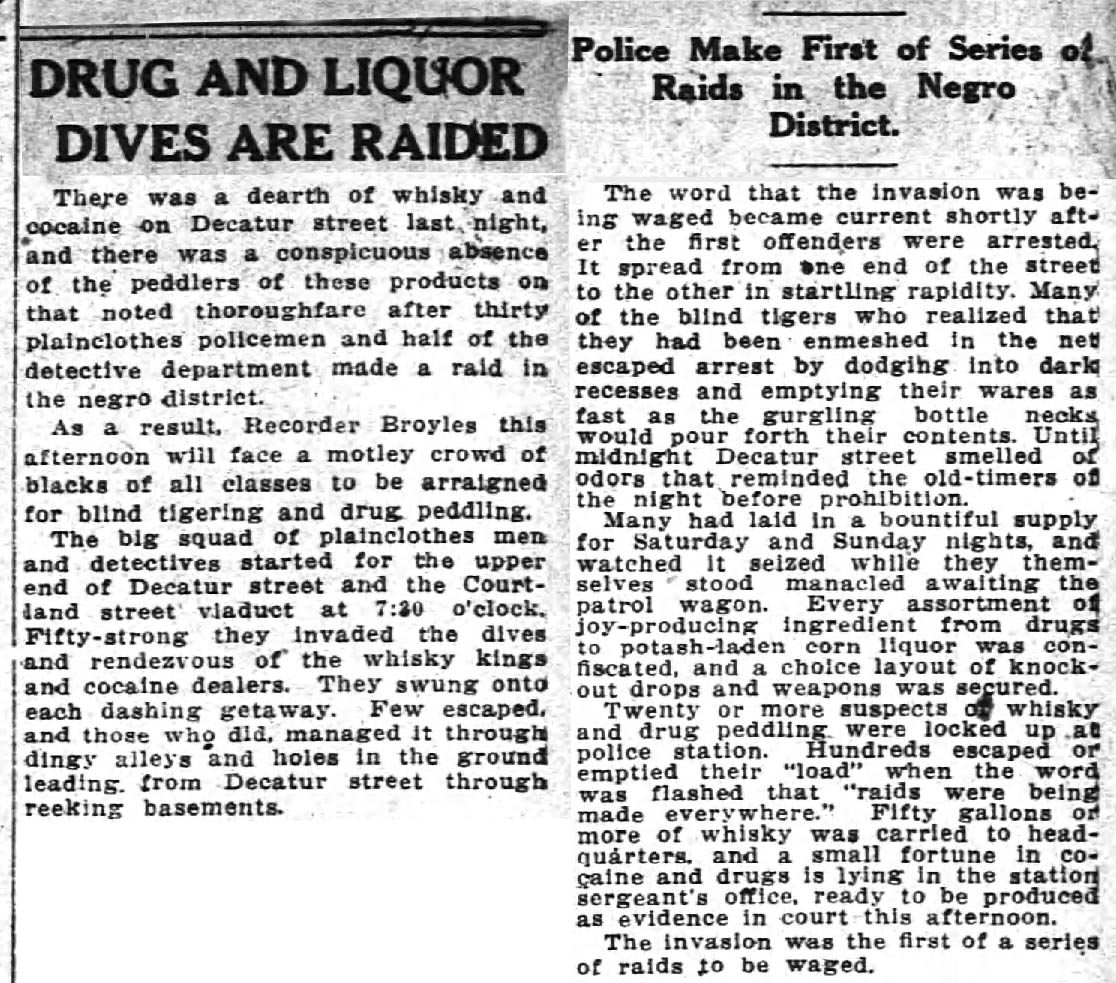

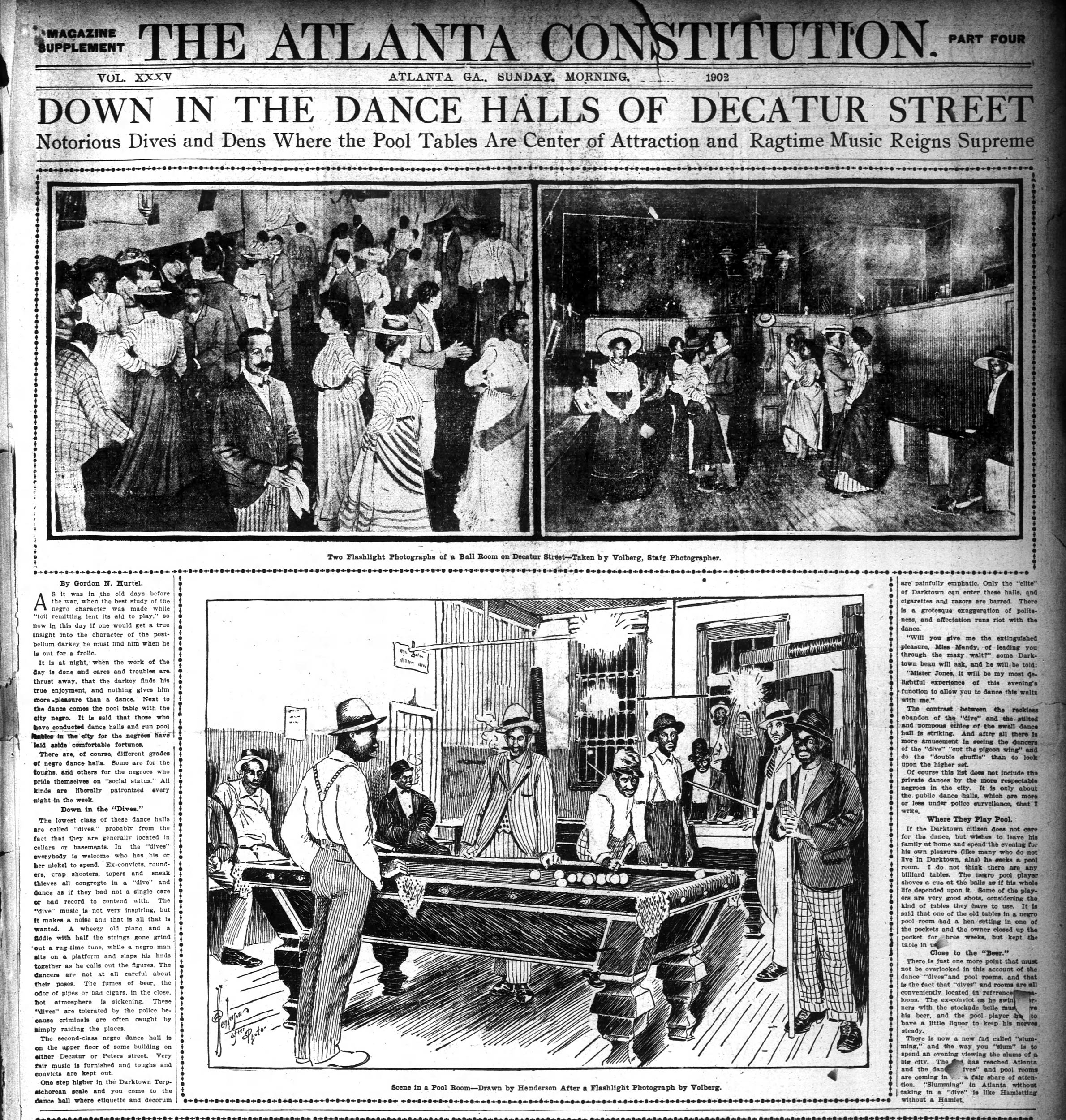

Overstating how Atlanta’s first Syrians, or any group for that matter, shaped the city would smack of a kind of historically inaccurate and idealized “Mayflowerism.” But as the current Syrian refugee crisis continues, it is now necessary and more important than ever to consider any and all enduring contributions of the first and current Syrian communities, as well as to consider the attitudes towards Syrian refugees’ arrival to Atlanta, and cities across America, back then and now. About 100 years ago, one could easily find stories about Atlanta’s “Syrian colony” in the Atlanta Constitution, and dozens of “Little Syrias” existed in other U.S. cities, notably New York, “the mother colony,” Chicago, Boston, Cleveland, Toledo, Detroit, even Worcester, MA, and Ross, ND. Did you know that in Dearborn Michigan, in 1916, 555 Syrians worked at the Ford factory? Or that among the 1,500 who perished in the sinking of the Titanic were Syrian refugees in steerage? Atlanta’s Syrian community is not mentioned in Gualtieri’s book “Between Arab and White,” but these immigrants, which likely first arrived in New York, called home a large swath of Decatur St. in the heart of downtown near the old police barracks. Today Decatur St. cuts across Georgia State University’s campus, but in the first quarter of the 1900s, it was where around 400 Syrians lived and many ran their own businesses. And, according to a 1902 article (see slider of images below), it was also an entertainment strip full of "dive bars" and "depravity" that set part of the backdrop for the 1906 Atlanta Race Riots (the NAACP would arise in 1909). The 1924 Federal Census listed 41 Syrian families in Atlanta, among them many surnames you may recognize, among them the Maloofs, Nours, Azars, Courys, Easseys, Feckourys, the Najours and many more.

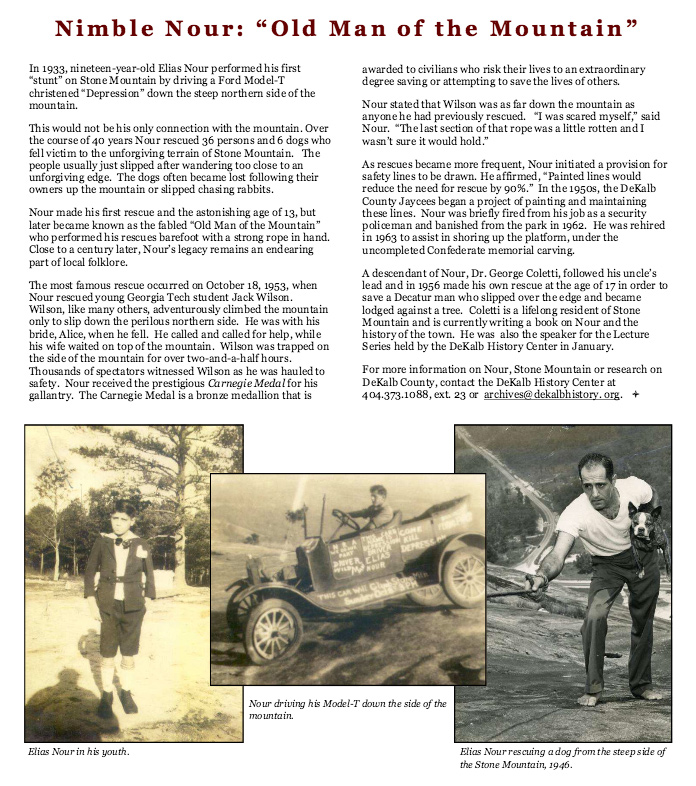

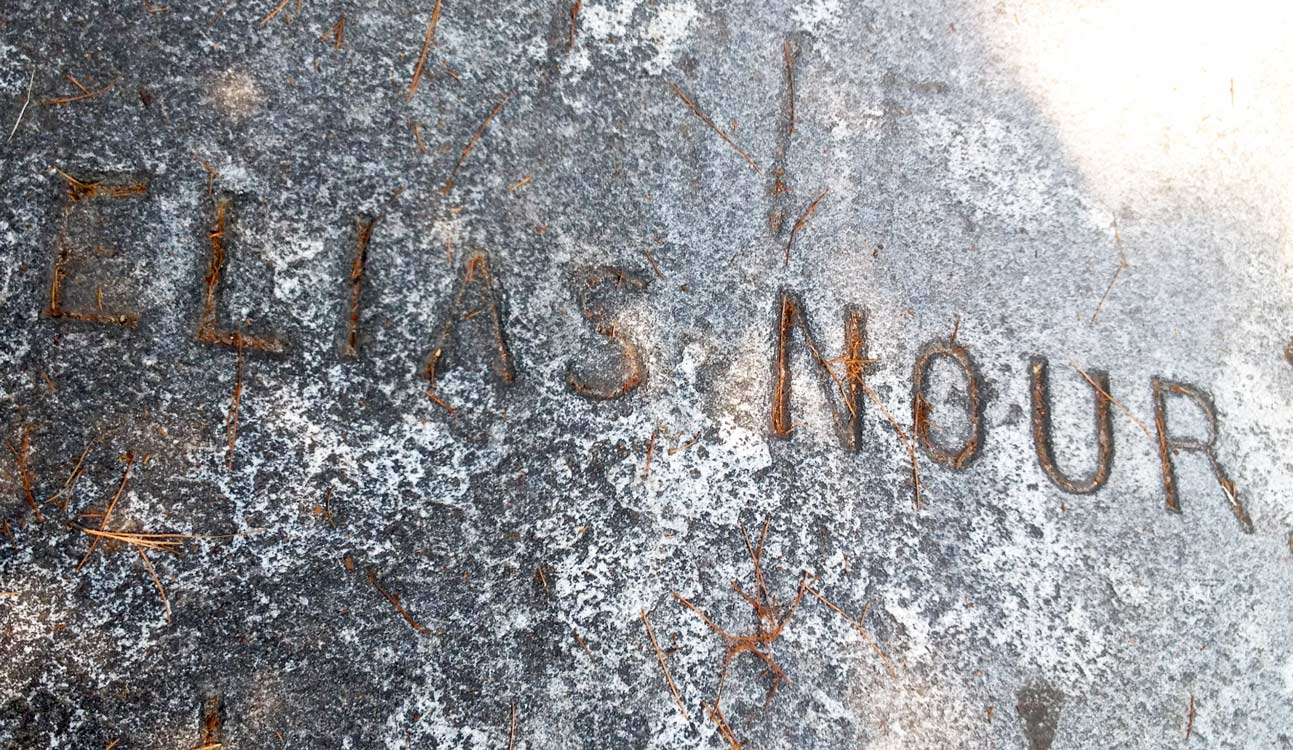

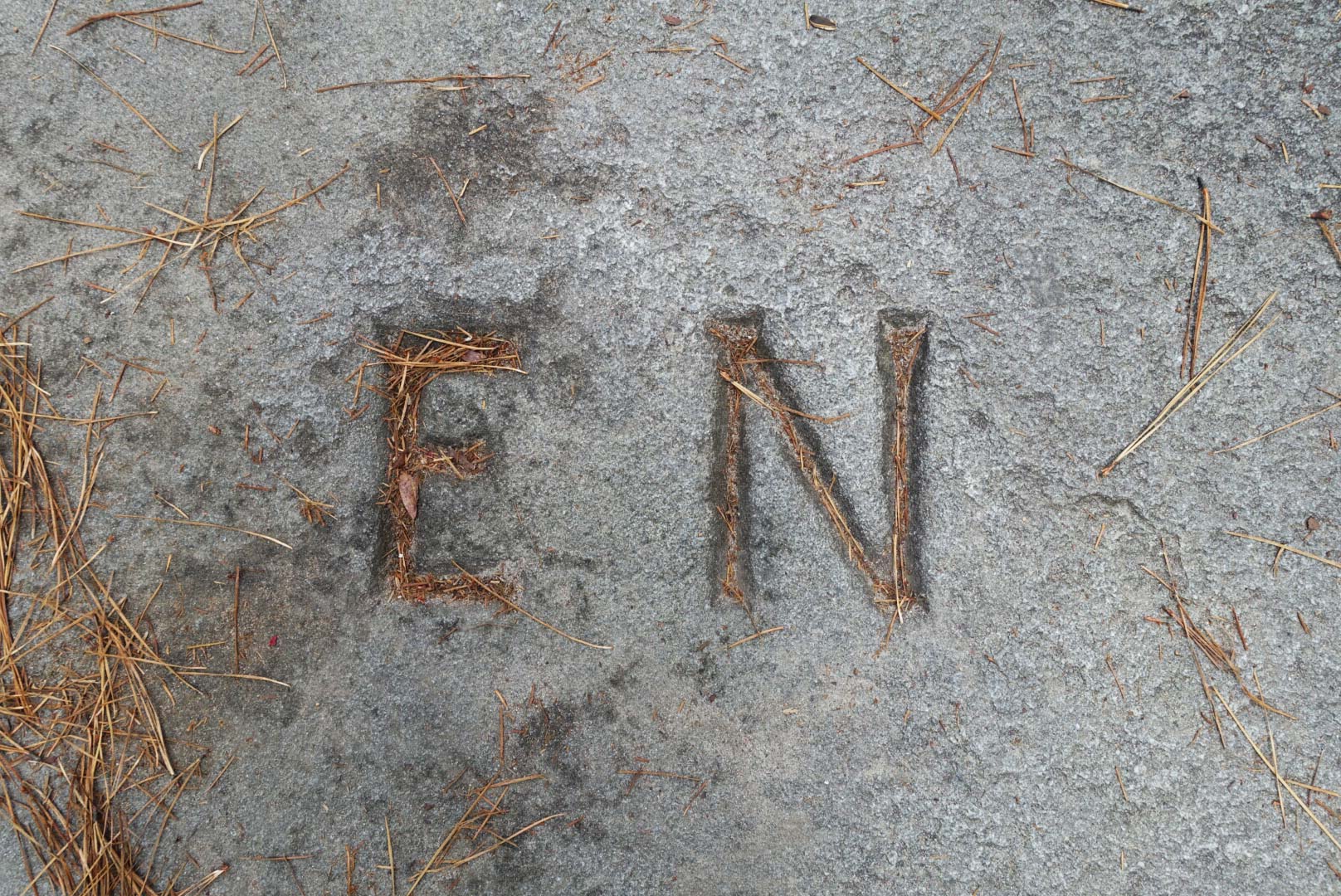

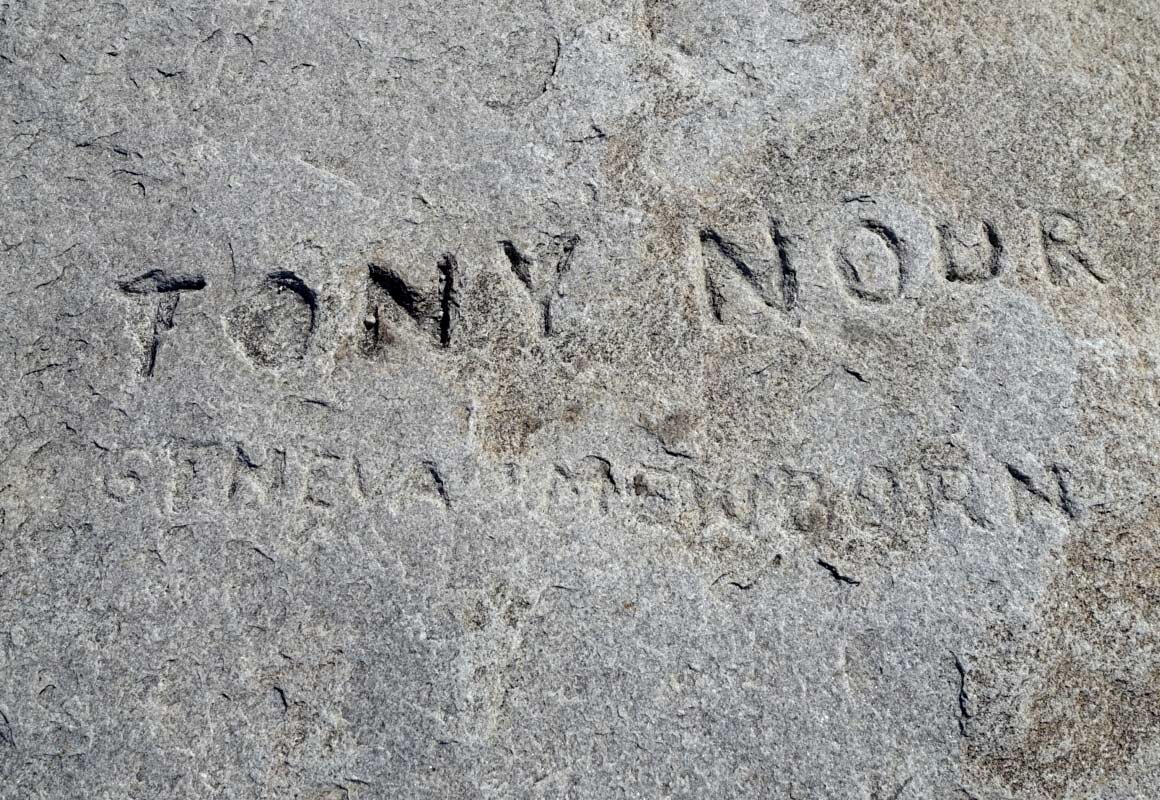

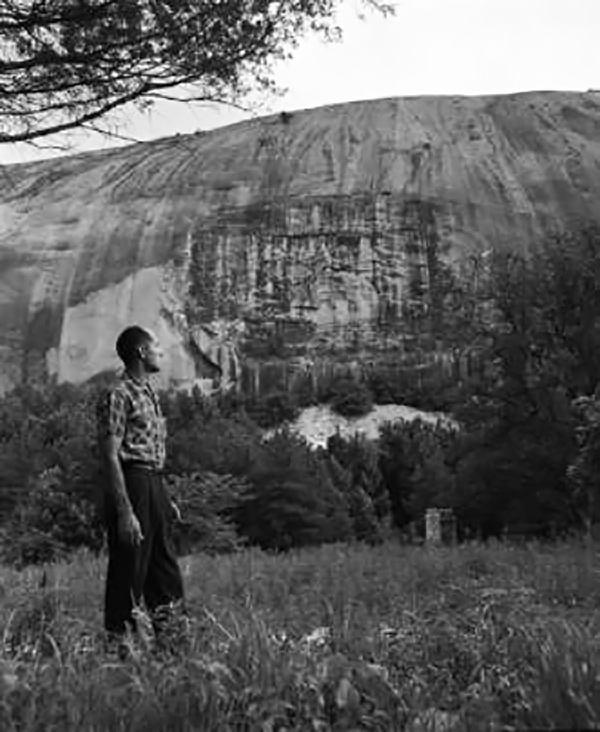

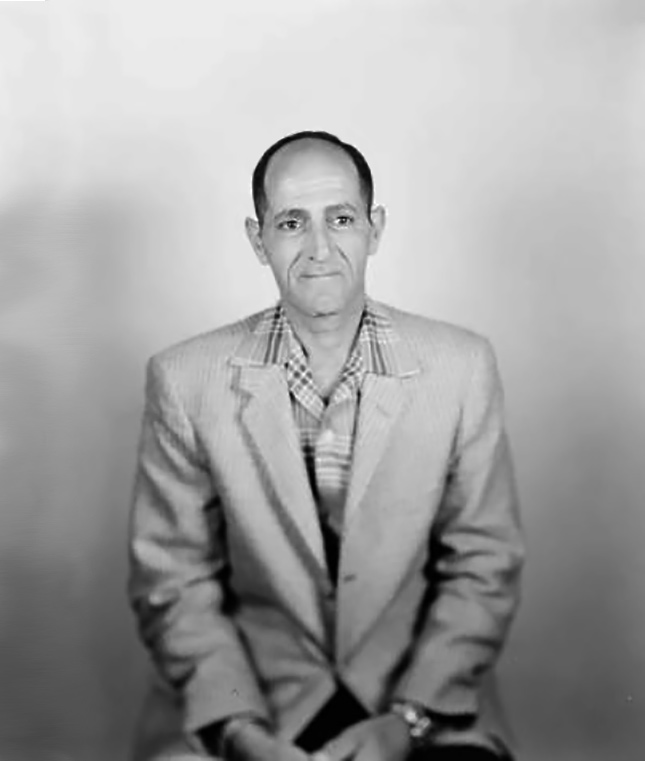

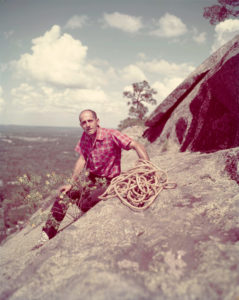

Elias Nour

In some cases, this “claiming whiteness” would appear to have possibly conferred privilege upon several celebrated Syrian-Lebanese families in the area. That Syrian businessman D.E. Nour, for example, owned a Stone Mountain bowling alley and a restaurant at the base of Stone Mountain, inside the old Wayside Inn, during the heyday of the Ku Klux Klan at the mountain says a lot (the Venable brothers also owned the Southern Granite Company, which owned nearby Arabia Mountain). Nour's son Elias later managed the family’s filling station and auto garage and went on to run his own refrigeration business. To this day you will find more than one carving on the mountain bearing his name or initials—“Elias Nour,” “Nour,” “E.N.” or “Tony Nour” (his brother)—and one of the roads leading into Stone Mountain Park is named Elias B. Nour Drive. Elias Nour passed away of emphysema at the age of 79 at a hospital in Atlanta in 1993, and even though he'd moved to Daytona, FL in the 1960s, he is still revered locally as the “Old Man of the Mountain,” because he rescued 36 people and several animals from on top of Stone Mountain at a time when there was no fencing to steer climbers away from the more treacherous areas (a fence was installed in 1963). In fact, after coming to the aid of a stranded Georgia Tech student and his wife, he earned a Carnegie Hero medal in 1953, among other accolades and awards. His grandson, Dr. George Coletti, 76, sometimes helped with such rescues, too, and currently lives in Stone Mountain with his wife and has self-published two novels inspired by the mountain. Popular culture of the day and consumer trends also helped pave the way for acceptance of new immigrants from the Middle East. Films such as “The Arab” and “The Sheik," and silent actor Rudolph Valentino himself, lent intrigue and romance to ‘The Orient’ and the ‘Near East,' as it was commonly referred then, but as the article "Orientalism in American Popular Culture" details, fascination with all things Middle Eastern and "Arabian" at the turn of the last century had much more complex and imperial ramifications. The shoe, of course, appears to be on the other foot now when it comes to the loss of such "privilege," and, these days, depictions in the media of Syrians, and practically anything or anyone Middle Eastern, are more often than not quite the opposite of "romantic."

St. Elias Antiochian Orthodox Church

Yet more newspaper articles detailed how Najour and other Atlanta Syrians united in 1921 to form an orthodox church in Atlanta, the most recent incarnation of which is St. Elias Antiochian Orthodox Church on Ponce de Leon Ave (prior to that it was St. Mary Syrian Christian Greek Orthodox Church at Woodward Ave. and Connally St. until a fire destroyed the building on March 18, 1956). Since we're on the subject of religion, Manuel Maloof was a Melkite Catholic, and the Syrians immigrants that arrived in Atlanta were predominantly Orthodox Christian, while other U.S. cities received more Muslim Syrians. This past September, St. Elias held its 41st Mid-East Festival. Also worth noting is that St. Elias on Ponce de Leon was just down the road from “Stonehenge,” the Venable Mansion located at Oakdale and Ponce de Leon (the first sculptor of Stone Mountain, Gutzon Borglum, was actually a dinner guest at Stonehenge the very night after the Klan declared the mountain its 20th Century rebirth place on November 25, 1915). Stonehenge, built in 1914 of Stone Mountain granite, is now St. John’s Lutheran Church (purchased for $60,000 in 1959). So much Atlanta history along just that stretch of Ponce de Leon Ave. Oh, and while I'm on the subject of Stone Mountain granite, I read that the store front of Harry's Delicatessen that became Manuel's Tavern was made of granite from Stone Mountain, too. The list is long of structures and monuments around the U.S. (and even Canada, Cuba, and Japan) that incorporate Stone Mountain granite (the Tidal Grey granite of Arabia Mountain in Lithonia was also used widely).

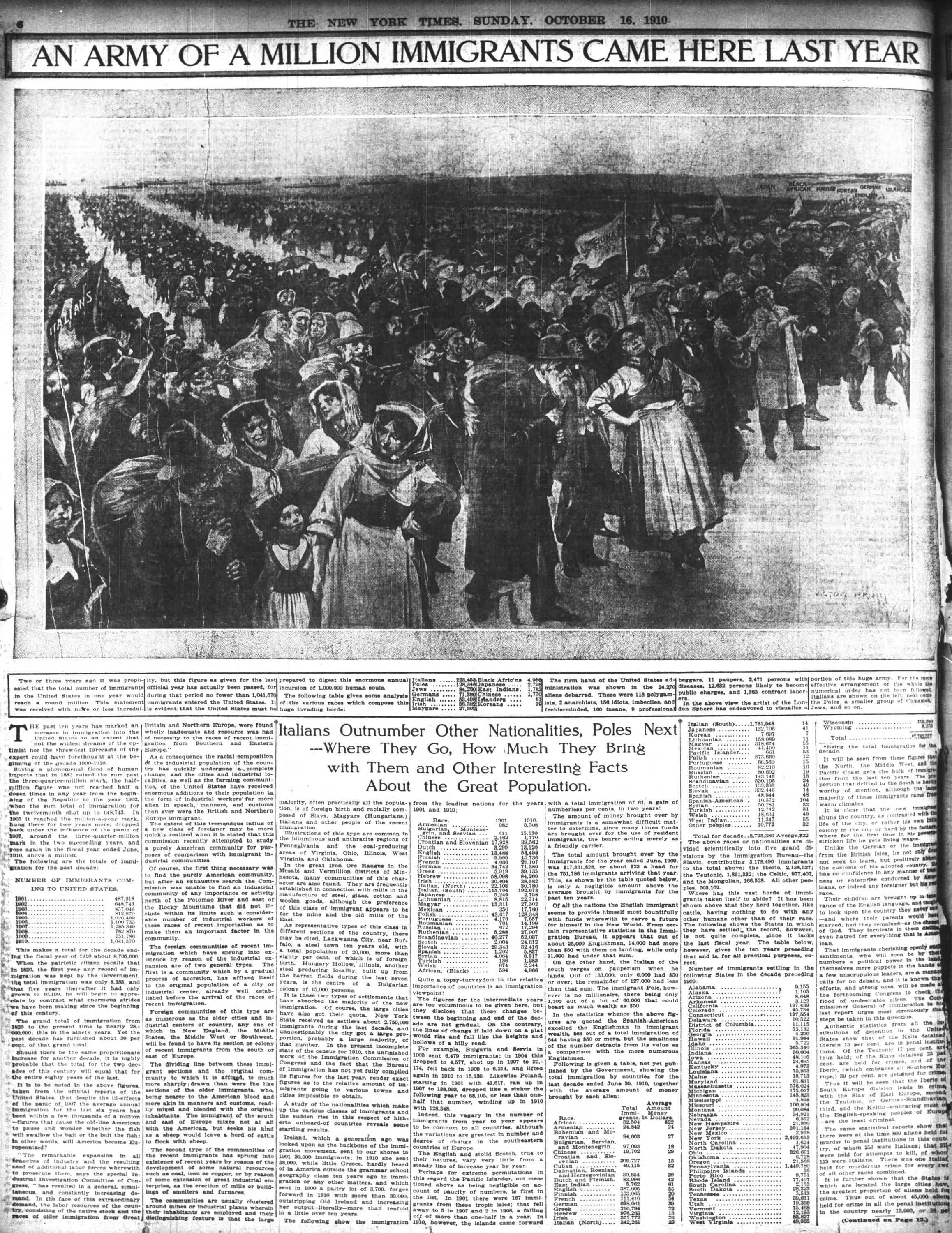

Yesterday's news often serves to remind us that current events are indeed part of a continuous cycle and are hardly ever—make that never—happening in a vacuum. The past truly holds so many of the keys to understanding the present. We have been here before with immigration, as have nations the world over, since man first put one foot in front of the other. Take this 1911 article in the New York Times, for example. "Bruce Walker, Autocrat of Canada's Immigrants" reveals Canada's much different approach to immigration a century ago (I admit that headline reminded me for a second of that TV show "Walker, Texas Ranger," though I never watched it). How very different from the way Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, born on Christmas Day in 1971, has been welcoming Syrian refugees into Canada this year. The more one studies history, the more one sees the pendulum ever swinging between war and peace. Periods of unrest follow brief periods of peace. War. Peace. War. Peace. Yesterday's enemies are today's allies. Nation friends one day turn to foes. Today’s Islamophobia looks an awful lot like yesterday’s anti-Semitism. It's as if countries take turns being the good guys and the bad guys, vilifying this group or another, and the endless grabbing for power often brings a lot of dangerous racist rhetoric with it—and much worse—in the guise of patriotism and protection.

Yesterday's news often serves to remind us that current events are indeed part of a continuous cycle and are hardly ever—make that never—happening in a vacuum. The past truly holds so many of the keys to understanding the present. We have been here before with immigration, as have nations the world over, since man first put one foot in front of the other. Take this 1911 article in the New York Times, for example. "Bruce Walker, Autocrat of Canada's Immigrants" reveals Canada's much different approach to immigration a century ago (I admit that headline reminded me for a second of that TV show "Walker, Texas Ranger," though I never watched it). How very different from the way Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, born on Christmas Day in 1971, has been welcoming Syrian refugees into Canada this year. The more one studies history, the more one sees the pendulum ever swinging between war and peace. Periods of unrest follow brief periods of peace. War. Peace. War. Peace. Yesterday's enemies are today's allies. Nation friends one day turn to foes. Today’s Islamophobia looks an awful lot like yesterday’s anti-Semitism. It's as if countries take turns being the good guys and the bad guys, vilifying this group or another, and the endless grabbing for power often brings a lot of dangerous racist rhetoric with it—and much worse—in the guise of patriotism and protection.

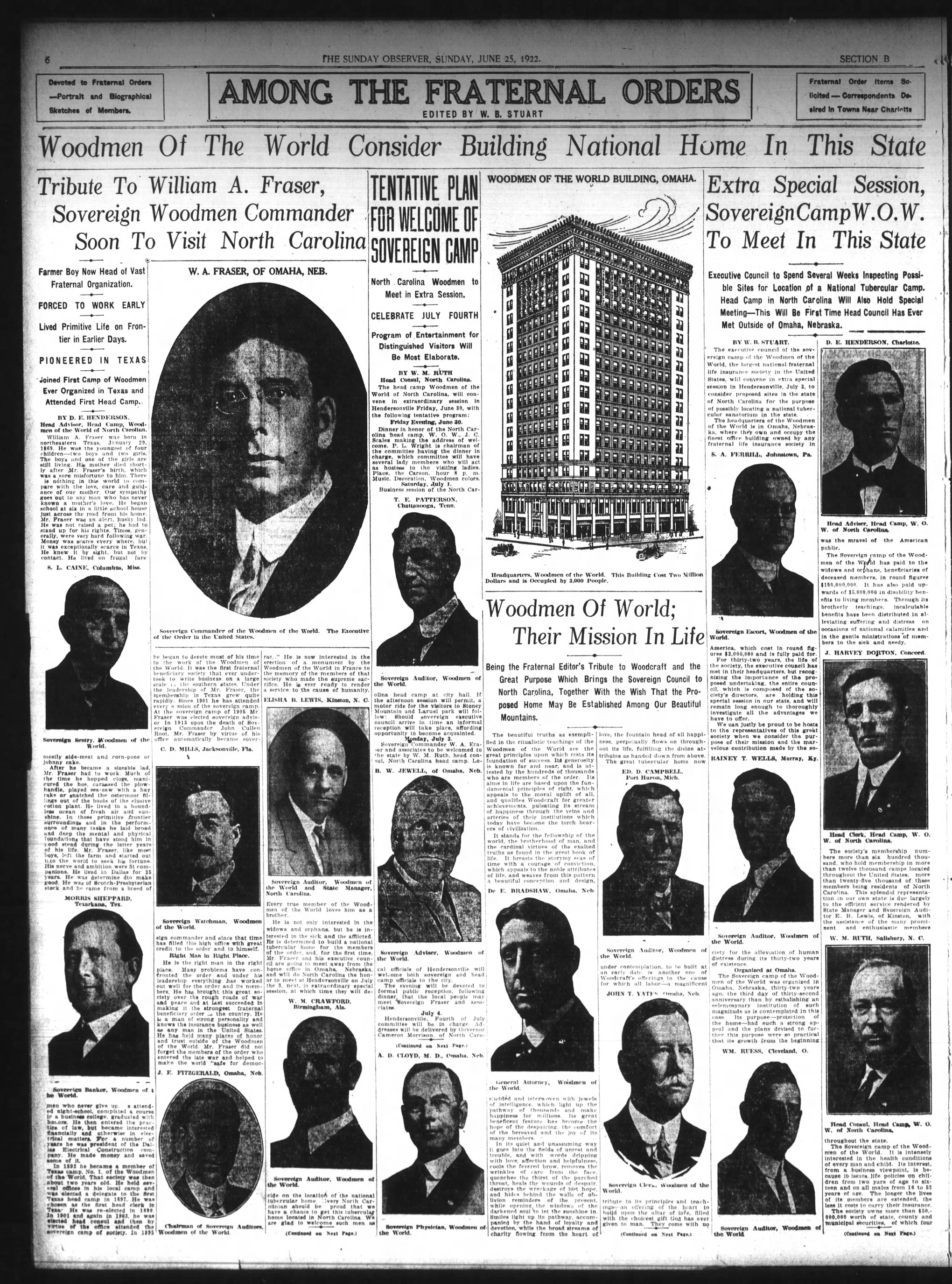

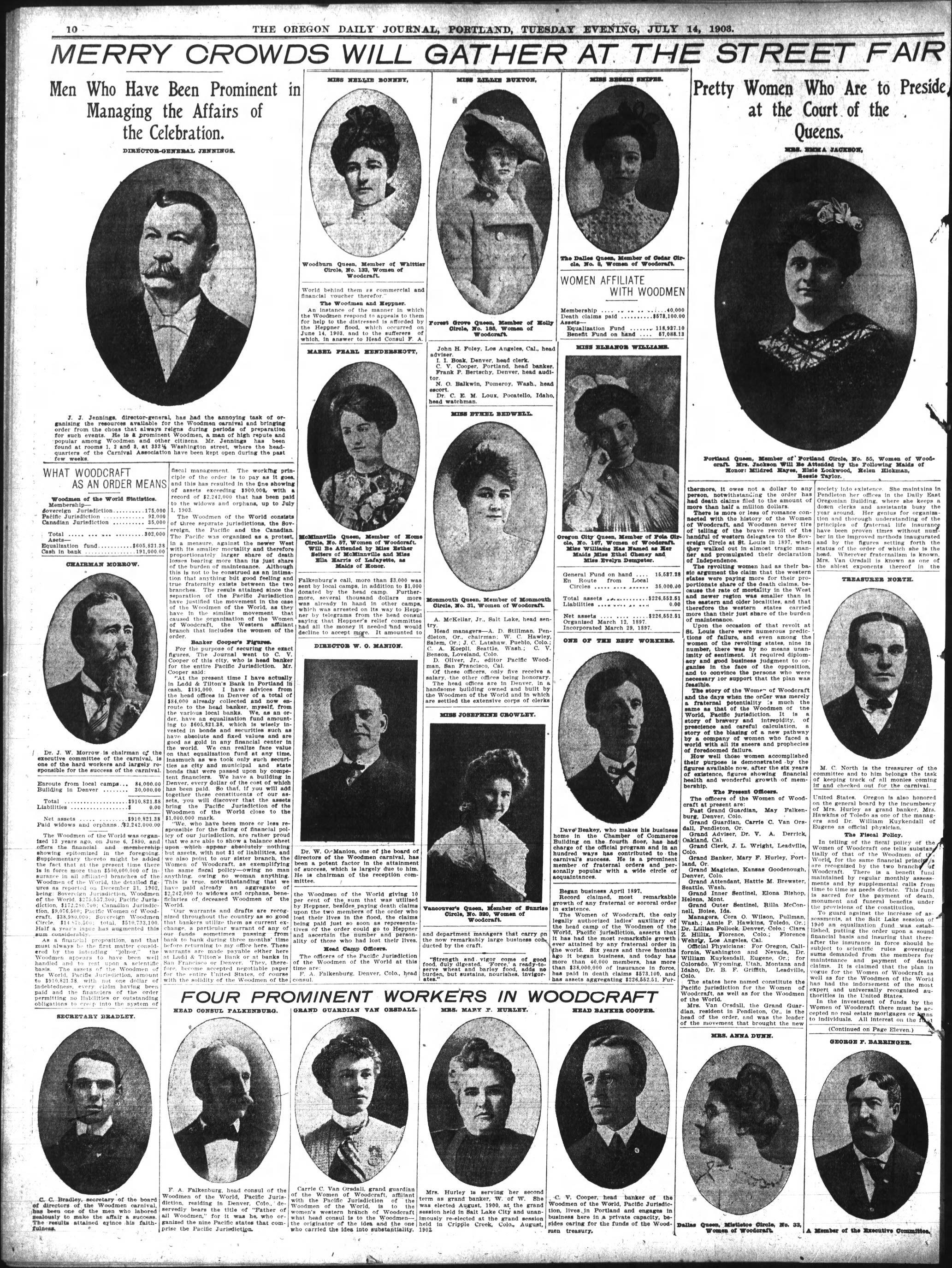

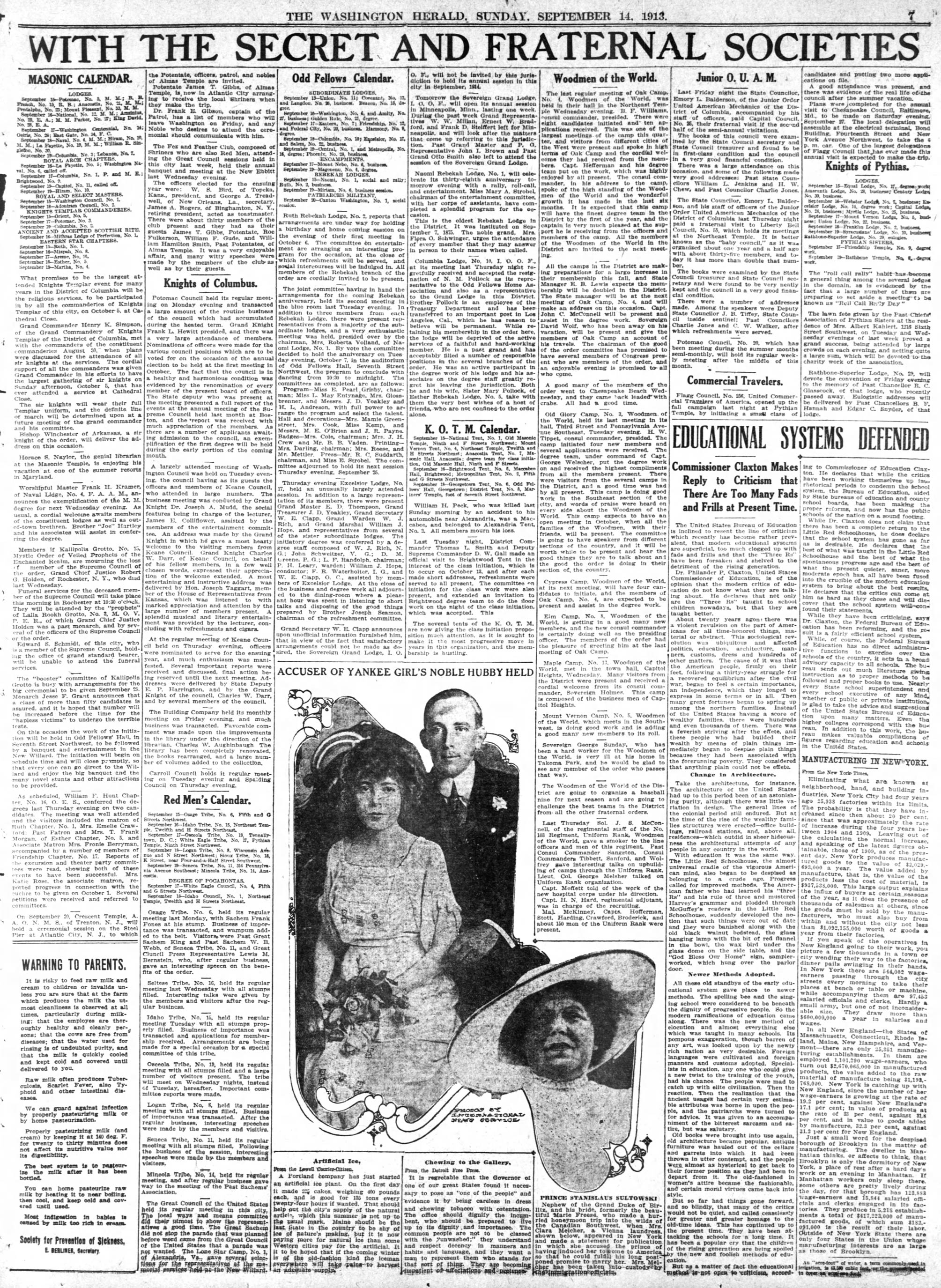

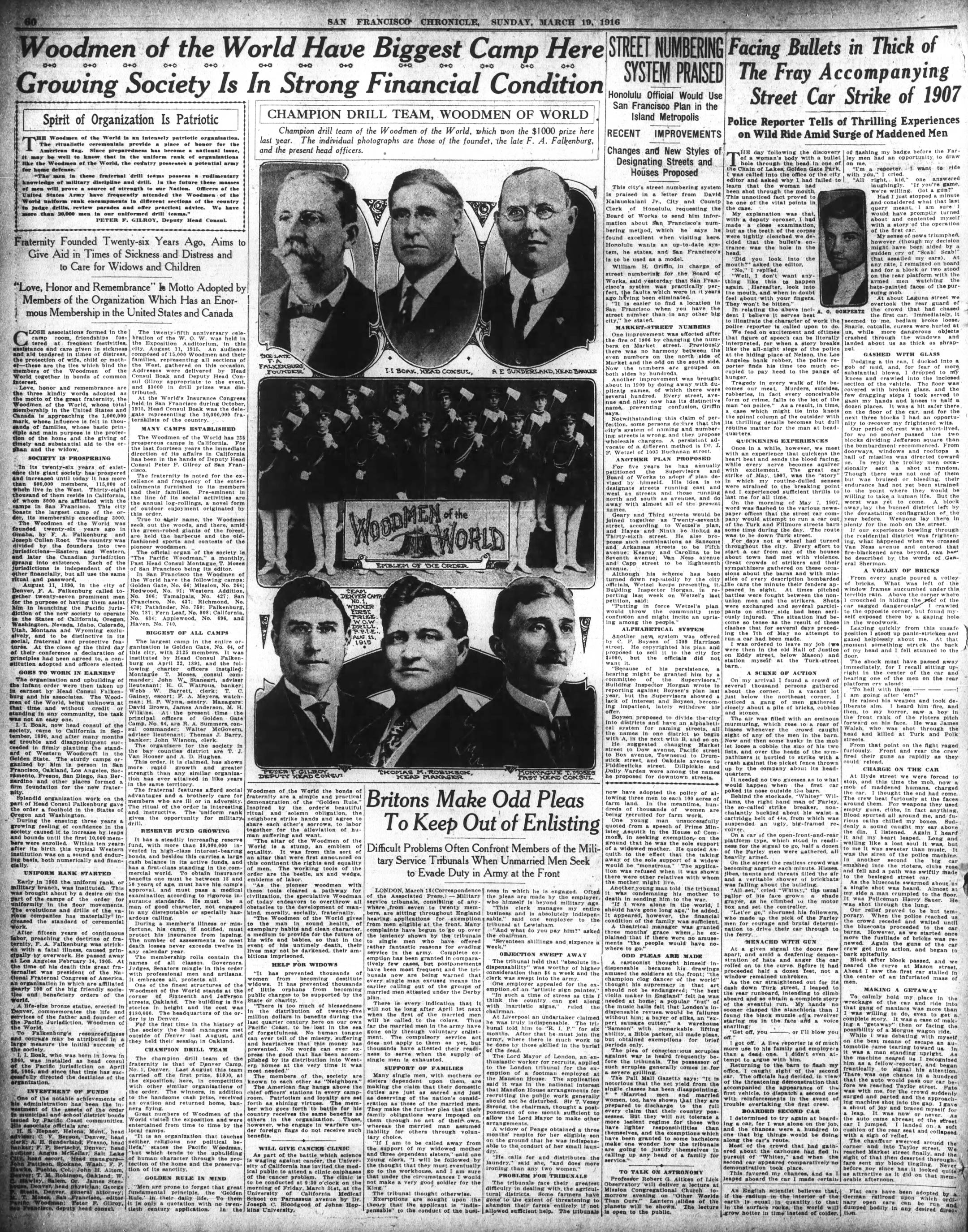

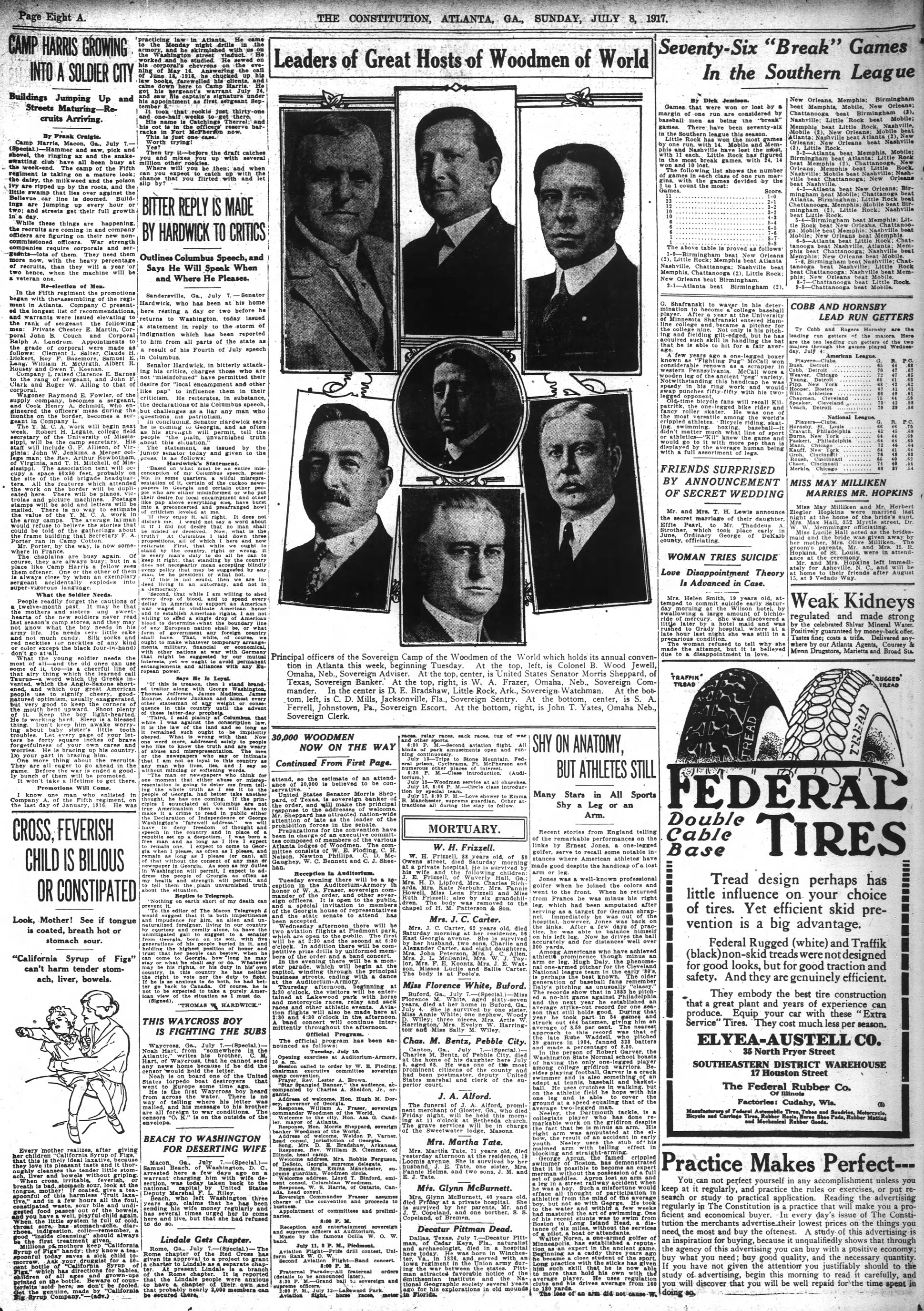

Fear mongering was at an all-time high during the early years of World War I, particularly after America entered the war in 1917, and not long after the politically powerful Klan reemerged in 1915. In addition to the Klan, numerous other fraternal orders at the time were also in the business of quote-un-quote protecting orphans and widows and America's purity. Newspapers had entire pages devoted to listing the activities and meetings of such fraternal (and secret) orders. Many such tax-exempt benefit societies even began selling insurance to its carefully culled members, such as did the Woodmen of the World, which turns 125 this year and is now called Woodmen Life.Woodmen membership in its early years was limited to white men aged 15-52. William J. Simmons, who founded the Second Era Klan at Stone Mountain, was also a Colonel in the fraternal order Woodmen of the World at the same time he started the Klan and was thus able to double-dip, so to speak, when it came to recruiting for the Klan, on the one hand, and selling insurance policies for W.O.W. to the very same recruits on the other. This might well explain why so many W.O.W. carvings remain on Stone Mountain and are among the largest and more elaborate carvings on the mountain. One carving (pictured below) for a J.J. Brown probably refers to the commissioner of agriculture under both Governor Slaton and Governor Dorsey. Who would've ever imagined that the United States Congress would one day enact the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act in 2002 (definitely will be reading up on terror insurance next).

Fear mongering was at an all-time high during the early years of World War I, particularly after America entered the war in 1917, and not long after the politically powerful Klan reemerged in 1915. In addition to the Klan, numerous other fraternal orders at the time were also in the business of quote-un-quote protecting orphans and widows and America's purity. Newspapers had entire pages devoted to listing the activities and meetings of such fraternal (and secret) orders. Many such tax-exempt benefit societies even began selling insurance to its carefully culled members, such as did the Woodmen of the World, which turns 125 this year and is now called Woodmen Life.Woodmen membership in its early years was limited to white men aged 15-52. William J. Simmons, who founded the Second Era Klan at Stone Mountain, was also a Colonel in the fraternal order Woodmen of the World at the same time he started the Klan and was thus able to double-dip, so to speak, when it came to recruiting for the Klan, on the one hand, and selling insurance policies for W.O.W. to the very same recruits on the other. This might well explain why so many W.O.W. carvings remain on Stone Mountain and are among the largest and more elaborate carvings on the mountain. One carving (pictured below) for a J.J. Brown probably refers to the commissioner of agriculture under both Governor Slaton and Governor Dorsey. Who would've ever imagined that the United States Congress would one day enact the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act in 2002 (definitely will be reading up on terror insurance next).

So, Donald Trump's “Make America Great Again” slogan (an echo of Nixon's "Make America First Again" slogan in 1968) and the terror and dangerous Islamophobia he stirs up with his abhorrent directive calling for "a complete and total shutdown of Muslims entering the U.S." (said at the start of Hanukkah no less) is eerily reminiscent of the same anxiety and panic fomented by the Klan, a good deal of which was in direct response to immigrants pouring into the U.S. in the late 19th Century (hundreds of thousands of these very immigrants actually repatriated during WWI so as to support their home countries in the war effort).

Me celebrating Obama’s reelection at Manuel’s Tavern on November 6, 2012

We should beware of anyone that would have us constantly afraid and in a perpetual dark night—and that would have us believe they control the light. And here's hoping the lights will be on at Manuel’s Tavern on November 8, 2016!