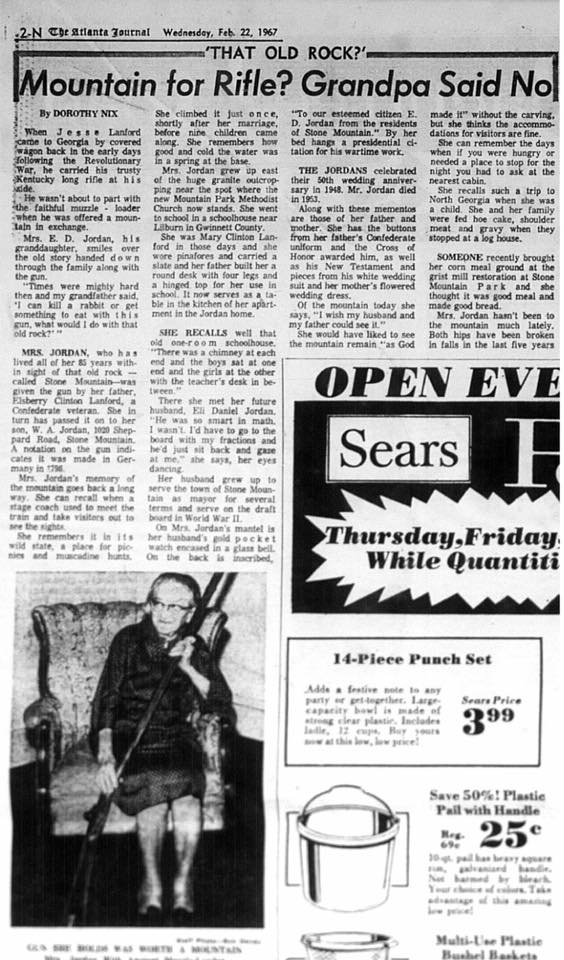

To think, my nephew Sam is directly related to the very people who could've owned the mountain for the mere sum of a Kentucky long rifle and perhaps changed the entire direction that it ultimately took. According to legend, that is. To my eyes, the name E.D. Jordan, mentioned in the article below, is even faintly visible among the numerous carvings on Stone Mountain (pictured). Mrs. E.D. Jordan (pictured) was the granddaughter of Jesse Lanford, and the said rifle is now in the possession of her grandson, Sam's father, who resides in Lawrenceville, GA. Before Stone Mountain Park signed a 50-year lease with Herschend Family Entertainment in 1998, it is believed the rifle had been on display at the park in either Confederate Hall or Memorial Hall.

Even months before the Confederate carving on the mountain was completed and Vice President Spiro Agnew would come to Stone Mountain for it's official dedication (in Richard Nixon's place), yet another local article perpetuating the myth about the rifle and the donkey trade was printed.

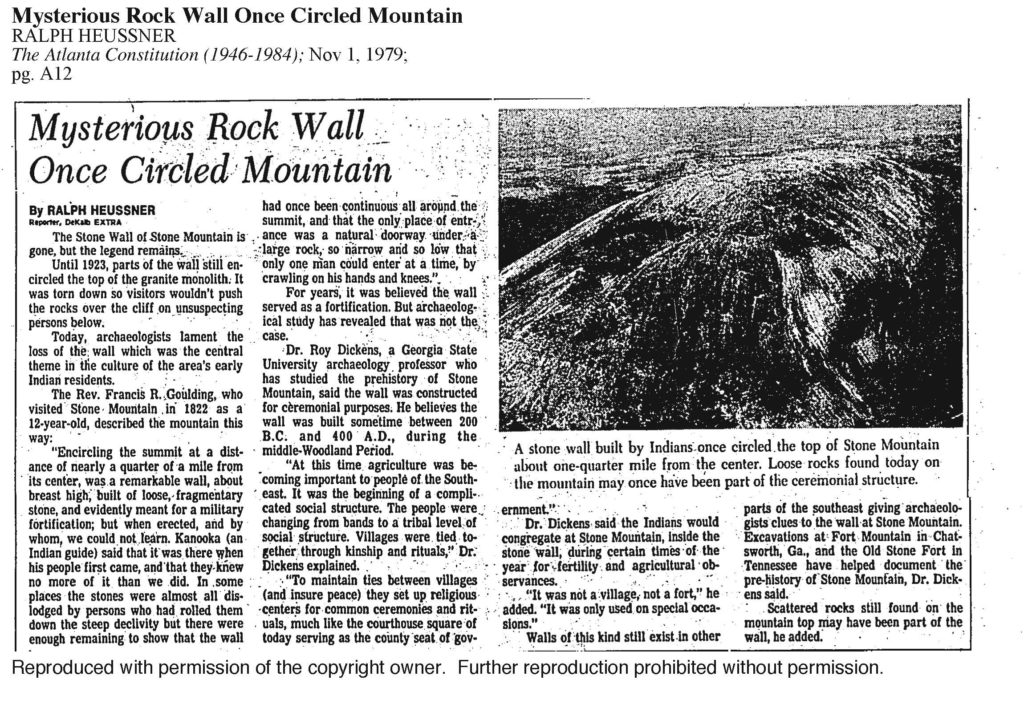

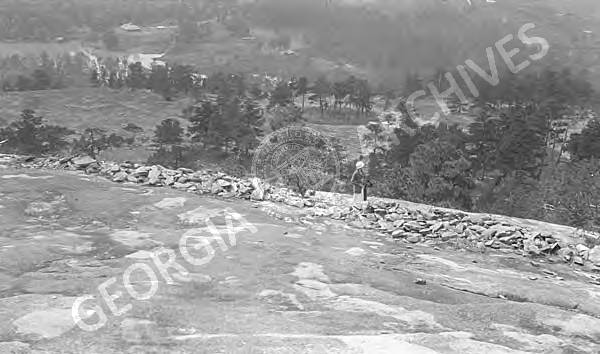

Sadly, very few actual relics and records from among the various Native American tribes in the Stone Mountain and surrounding Dekalb County area were ever preserved (I mean, at the mountain proper, as it's conceivable that what artifacts didn't end up in the hands of private citizens ended up in the Smithsonian, where other Native American relics from Georgia ended up. For example, early European developers, probably naive about their historical value, removed numerous structures on top of the mountain, believed to have been associated with Native American ceremonies, to build a hotel and other commercial structures. Tales like these were repeatedly put forth as part of white folklore and basically portrayed the Indians as fools to trade their sacred lands for a mere gun and a donkey, and they only served to perpetuate a narrative wherein the Indians appeared almost complicit in losing their lands to white land-grabbers. History has typically been written by those with the power and means to do so, and I believe in this case, many legends persisted to "justify" and mythologize how it came to be that white men, likely coercively, took possession of an actual mountain from area tribes.

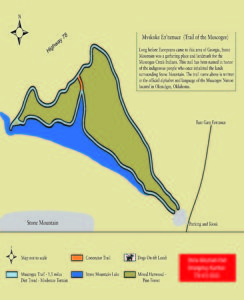

The actual details of Native Americans ceding their lands in Georgia (and throughout the United States) are not the stuff of romanticized campfire yarns. A great deal can be learned from reviewing two U.S. government treaties with the Creek Indians (also known as the Muscogee) the 1790 Treaty of New York and the 1821-1825 Treaty of Indian Springs. Stone Mountain Park has a 1.4-mile trail named in honor of the Native Americans, but little else about the Confederate memorial park deals with the history or year-round celebration of the Native cultures, a subject I often return to, especially last year during the long, moving campaign at Standing Rock. A false claim that is far too often repeated as fact is that George Washington's emissary, Colonely Marinus Willett, ever met with Alexander McGillivray, the Creek (Muscogee) Chief, and other Native American delegates on top of Stone Mountain.

The actual details of Native Americans ceding their lands in Georgia (and throughout the United States) are not the stuff of romanticized campfire yarns. A great deal can be learned from reviewing two U.S. government treaties with the Creek Indians (also known as the Muscogee) the 1790 Treaty of New York and the 1821-1825 Treaty of Indian Springs. Stone Mountain Park has a 1.4-mile trail named in honor of the Native Americans, but little else about the Confederate memorial park deals with the history or year-round celebration of the Native cultures, a subject I often return to, especially last year during the long, moving campaign at Standing Rock. A false claim that is far too often repeated as fact is that George Washington's emissary, Colonely Marinus Willett, ever met with Alexander McGillivray, the Creek (Muscogee) Chief, and other Native American delegates on top of Stone Mountain.

The crucial Indian delegation took place in New York. Sadly, this meeting eventually resulted in the Creeks fatefully ceding all of their lands to the State of Georgia between 1790 and 1821 via the Treaty of New York and subsequent Treaty of Indian Springs before Indian Removal.

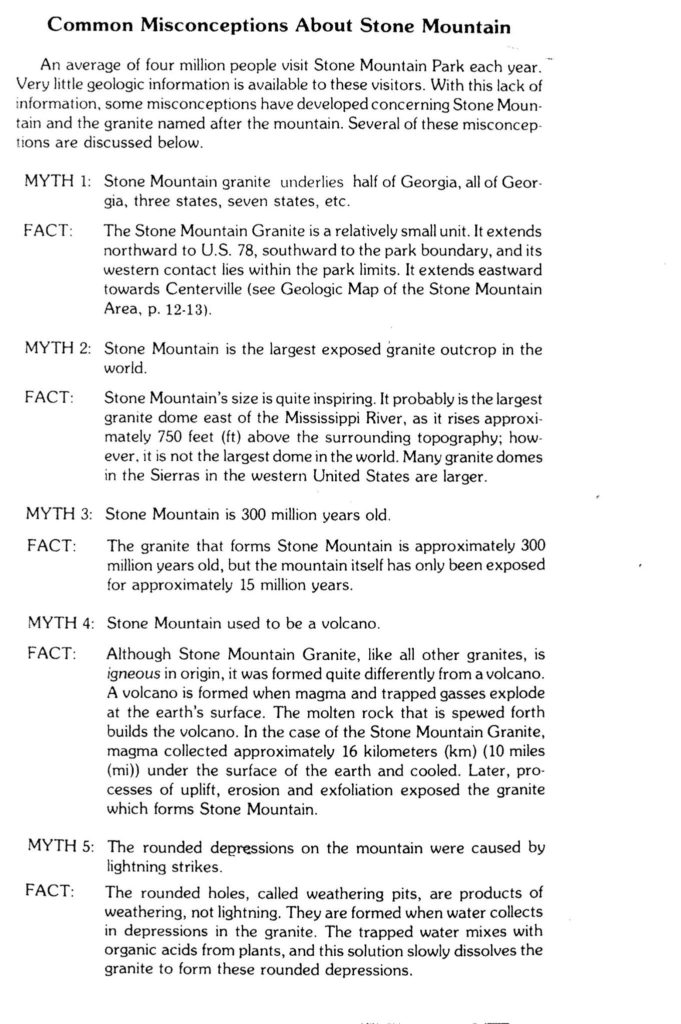

Here are more misconceptions about Stone Mountain (from the 1980 Geologic Guide To Stone Mountain Park by Robert L. Atkins and Lisa G. Joyce, a publication of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources with the Georgia Geologic Survey).