![]()

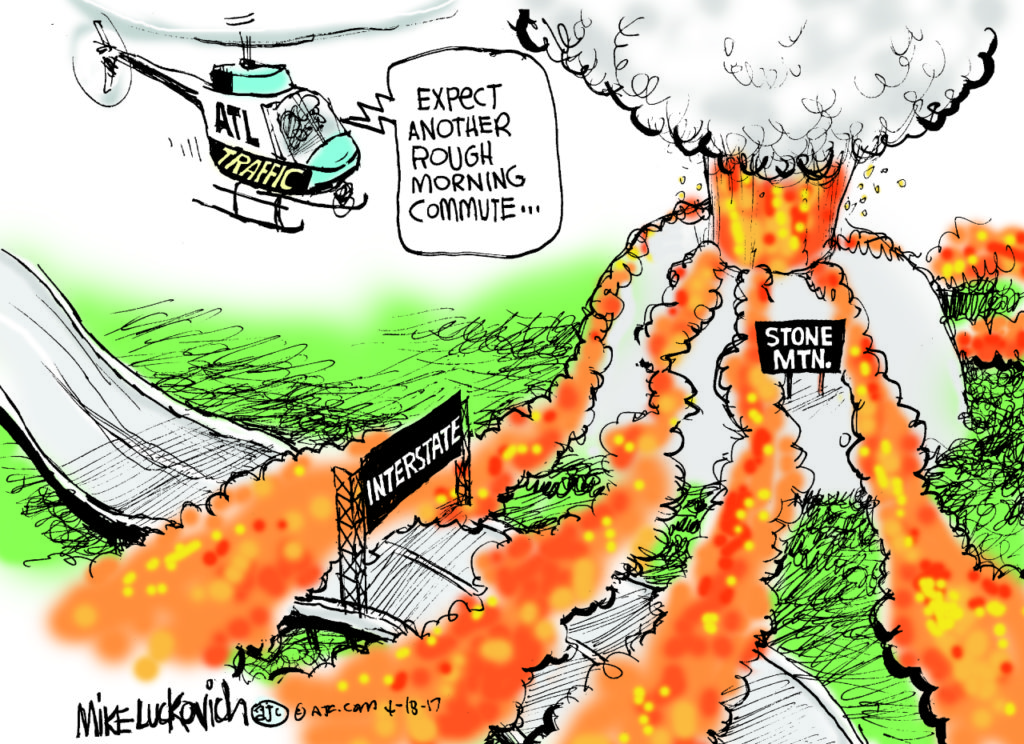

The fiery I-85 bridge collapse back in April reminded me of the approaching centennial of the Great Atlanta Fire of 1917 this May 21st and Atlanta’s long-term relationship with fire and its near obsession with making itself “fireproof.” Fire is intimately involved with Atlanta’s creation narrative, which features the phoenix rising from flames and ashes. A conspicuous amount of stone and durable granite also figures in Atlanta’s earliest design and development, and Atlanta is in many ways inextricably linked with that top tourist attraction and problematic Confederate monument in Metro Atlanta — Stone Mountain.

"Atlanta From the Ashes" sculpture in Woodruff Park in January 2017

The city’s first fire (surprisingly less devastating than the Great Atlanta Fire) famously occurred during the Siege of Atlanta in November 1864, when General William Tecumseh Sherman and his troops burned down most of the city and other parts of Georgia along his March to the Sea. Then, just nineteen years after Sherman’s searing destruction (thirty-four years before the Great Atlanta Fire), a prominent downtown hotel, The Kimball House, burned down on August 12, 1883 (ironically, that same lot was once occupied by The Atlanta Hotel near the old Union Depot, both turned to cinders by Sherman’s troops). The Kimball House was then rebuilt to be bigger and even more impressive — and, most importantly, it was now touted as “fireproof” — and reopened in April 1885 in grand fashion, only to be demolished in 1959 and reincarnated as a present-day parking deck. It would not be the first or last prominent building in the city of Atlanta to be gutted by fire or razed for a parking lot. For example, the former Masonic Temple at Peachtree St. & Cain St. (now Andrew Young International Blvd.) went up in flames on September 7, 1950, and is now the site of a parking structure.

Rock

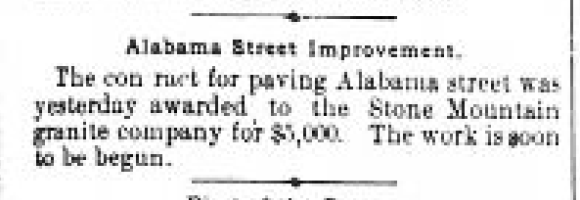

Naturally, being “fireproof” was a selling point, not only in Atlanta’s earliest days as it entered Reconstruction, but for decades thereafter, well into the 20th Century. Repeated fires put rock quarries and granite companies such as the Stone Mountain Granite and Railway Company and the Atlanta, Stone Mountain, and Lithonia Railway at a considerable advantage, particularly Atlanta brothers William and Sam Venable of the Stone Mountain Granite Company. But the fear of fire was only one factor that helped catapult Georgia’s granite industry into a prime position to thrive and amass power and wealth from the rock dubbed “white gold.” (Granite actually does have a melting point and can disintegrate in fire). Another was the major push by politicians and granite company shareholders to use materials and resources from Georgia, such as granite, over those from other states, such as oolitic limestone from Indiana.

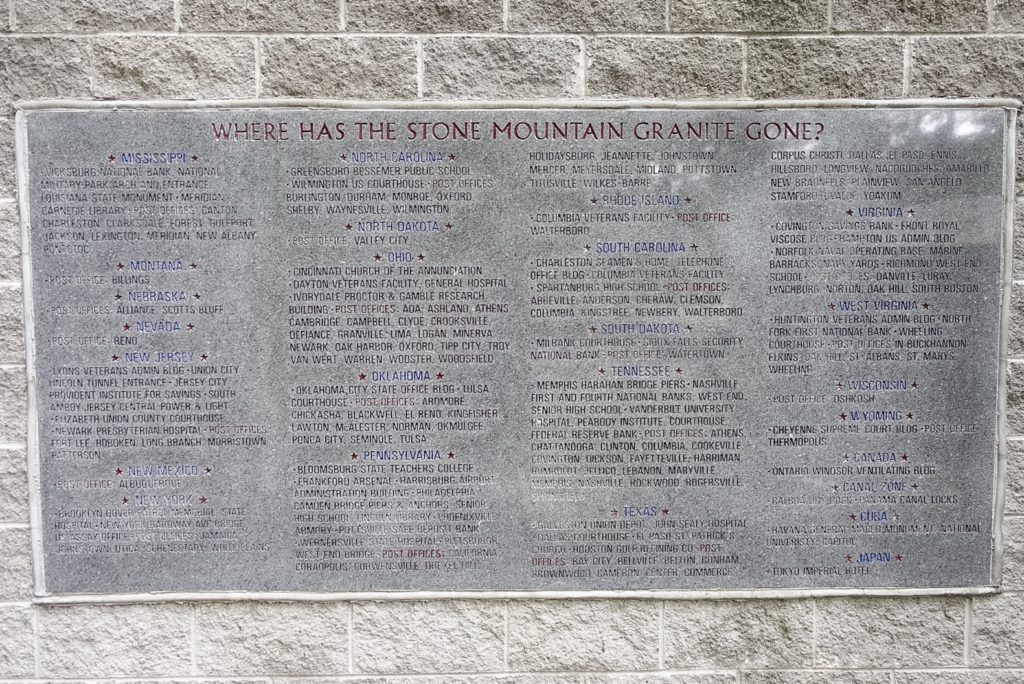

Georgia’s granite companies received plenty of big federal contracts, too, like the one in May 1916 to build the Marine barracks in Norfolk, VA [Atlanta Constitution; May 4, 1916]. Granite was still such a big industry in 1930 that Atlanta even welcomed a new amateur baseball league, the Granite League, comprised of amateur players from Stone Mountain, Clarkston, Tucker, Lithonia, Grayson, Brookhaven, Chamblee, Scottdale, and more. They had four matches that year with Piedmont League, Sewanee League, the Dixie League, Fulton League, and the Georgia League. In 1935, the Atlanta Constitution reported that Mussolini's invasion of Ethiopia "resulted in new business for Georgia's marble and granite quarries" as a Cuban dealer visited Atlanta. In 1938, government officials still promoted jobs in the granite industry as a way to keep people off the poor rolls. It wasn't all fun and games, though, as numerous stonecutter strikes for better wages and working conditions grew violent and sometimes deadly, and there was always a steady stream of accidents at the quarries in Stone Mountain and Lithonia.

Piedmont—The name "Piedmont" comes from the French term for the same physical region, literally meaning "foothill," ultimately from Latin pedemontium, meaning "the foot of the mountains.” [Wikipedia]

Lithonia—“city/town of stone” [Wikipedia]

Ebenezer—Hebrew (ebhen hā-ʽezer): stone of help; from the application of this name by Samuel to the stone which he set up in commemoration of God's help to the Israelites in their victory over the Philistines at Mizpah (1 Samuel 7:12) [Merriam Webster]

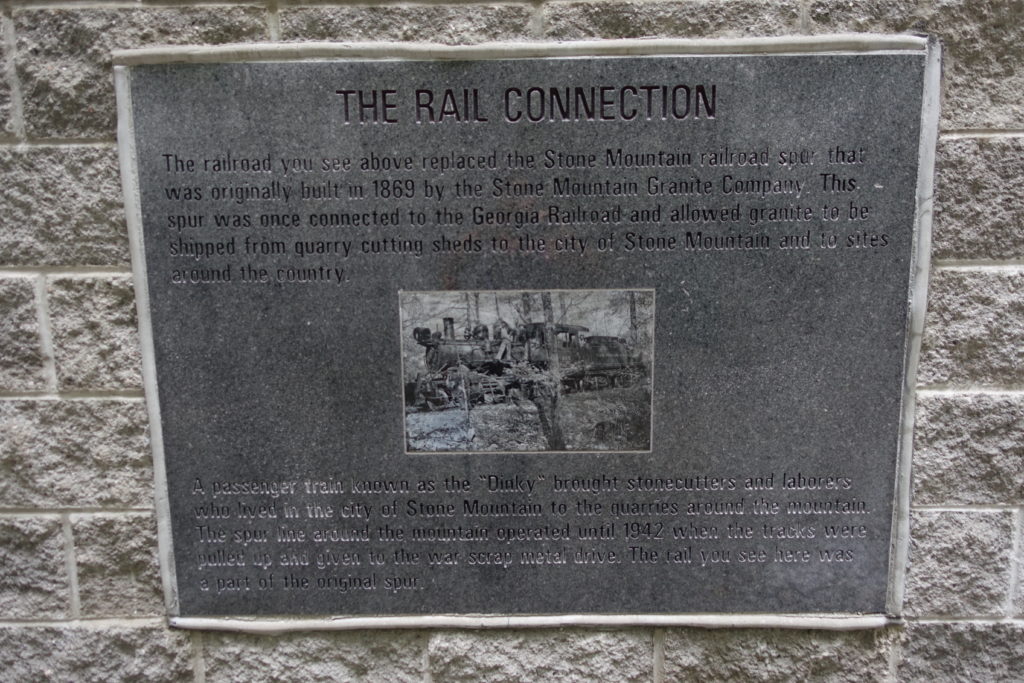

Atlanta’s city seal depicts a phoenix ascending from flames and is flanked by the dates 1847, the year of the city’s incorporation, and 1865, the year the Civil War ended. Atlanta’s identity as, first and foremost, a railway town had been secured years earlier when it drove in the stake for the granite Zero Mile Maker. [Edited to add: the Zero Mile Marker moved to the Atlanta History Center in late 2018, which classifies the marker as marble and not granite; 11/06/18 ] The city of Stone Mountain was also officially incorporated in 1847 and served as a pivotal connection point with Atlanta and Augusta along the 171-mile Georgia Railroad, especially as the railroad was a more efficient means of transporting the seemingly unlimited supply Stone Mountain granite than a horse and buggy (in recent years the Georgia Railroad had to account for using slave labor to build itself and the selling and trafficking of slaves). Stone Mountain Granite Company was one of the consignees of the Georgia Railroad (Atlanta Constitution; July 20, 1870), and even the Georgia Railroad’s roundhouse in Augusta was made of Stone Mountain granite (Atlanta Constitution; June 20, 1869). Though no Civil War battles were ever fought at the mountain itself, Sherman and his troops, notably Garrard’s Cavalry, did pass through Stone Mountain during their March to the Sea, even likely camping in Shermantown (so named in years later), and destroyed portions of the railroad in Stone Mountain Village, leaving behind “Sherman’s neckties” at the time.

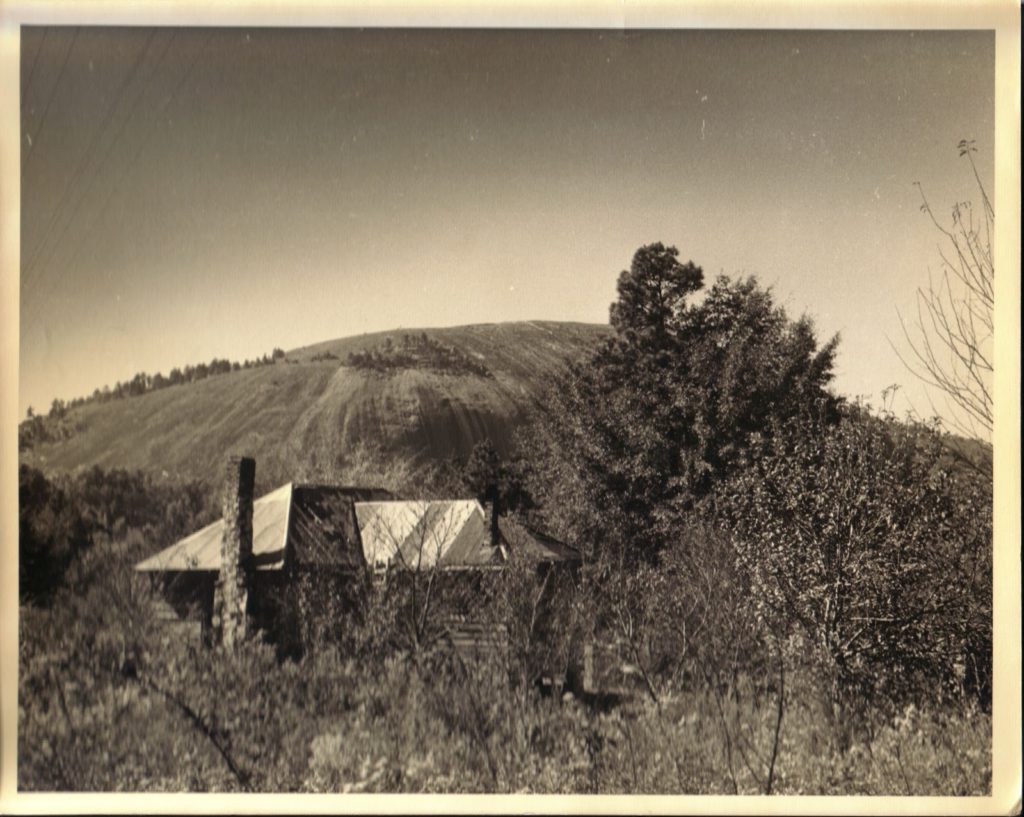

Before it officially took the name Stone Mountain in 1847, early European settlers in the area called it Rock Mountain, Rock Fort Mountain, and New Gibraltar. Even earlier, Spanish explorer Juan Pardo referred to it as Crystal Mountain, and the Creek Indians called it Lone Mountain.

Today numerous structures made of granite quarried in Stone Mountain and Arabia Mountain and Pine Mountain in nearby Lithonia (Elberton later became the center of Georgia’s granite industry) still stand throughout the city of Atlanta, particularly along the old rail corridors currently being restored for the Atlanta BeltLine. Just follow the tracks, and you’ll see how Stone Mountain granite runs through the city. I climb Stone Mountain a lot for I Am the Mountain, and I grew up in Stone Mountain, so perhaps owing to a particular law of physics — a space-time-frequency correlation with pattern recognition, if you will — I notice the mountain’s granite all over Metro Atlanta. Whenever I’m driving through Atlanta’s historic neighborhoods and main arteries and side streets — Peachtree St., North Avenue, Memorial Drive, Ponce de Leon Ave., Moreland Ave., Piedmont Ave., 10th St., Monroe Dr., N. Decatur Rd., E. Ponce de Leon Ave., Glenwood Ave., Hosea Williams Drive, Rockbridge Rd., East Lake, N. Highland Ave., and Whitefoord, to name just a few — I can’t help seeing the many old buildings, homes, churches, remnants of site walls, original neighborhood gateways, and even curbs constructed of it. Cities closest to the mountain like Stone Mountain and nearby Pine Lake utilized the stone heavily, so it's visible everywhere you look. In most cases it seems carefully preserved and has even been reincorporated into newer structures. But in other places it's abandoned, crumbling, or tagged with graffiti or, such as in the Old 4th Ward along North Avenue, covered completely or partially by colorfully painted murals (without regard for the historic aspect of the rock?).

African American men and women posed for portrait on granite steps of Atlanta University |

Water

Atlanta’s that rare major city without a port (but now possessing the world's largest aquarium at 6.3 million gallons of water), so when the Great Fire of Atlanta struck on May 21, 1917, hitting the Old Fourth Ward particularly hard, it took firefighters from all over Georgia, and as far away as Chattanooga, to put out the blaze that was ultimately stopped with dynamite blasts. Just as Atlanta moves to commemorate the centennial of the Great Fire this May 20 in the Old 4th Ward, the city is ever closer to having its largest water supply ever over at the old Bellwood Quarry, which was both a granite quarry and a prison labor camp, as well as a work farm a century ago. According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, "the $300M project will provide 2.4 billion-gallon reserve of raw drinking water." Interestingly enough, Jim Conley, who was also questioned in Mary Phagan's murder at the National Pencil Company (see History Background), was at one time a convict at Bellwood. As was later Hugh D. Gravitt, the driver who fatally struck Margaret Mitchell.

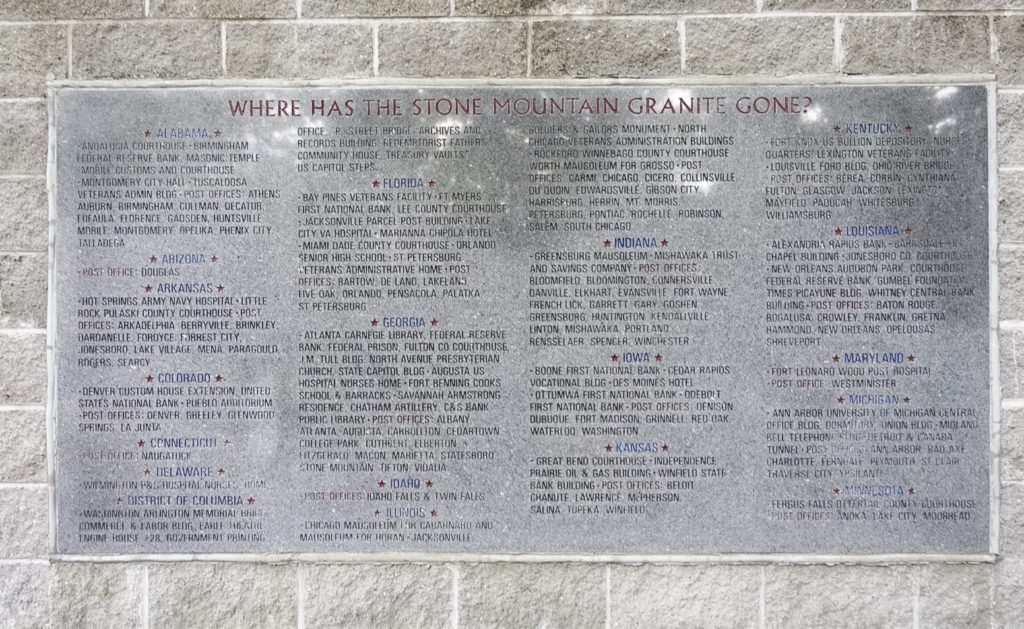

Some Metro Atlanta & Georgia Locations Featuring Stone Mountain Granite

- Atkins Park gateway

- Atlanta Botanical Gardens

- Atlanta Carnegie Library

- Atlanta Federal Penitentiary

- Atlanta First United Methodist

- Atlanta Post Office

- Burns Cottage

- Central Presbyterian Church

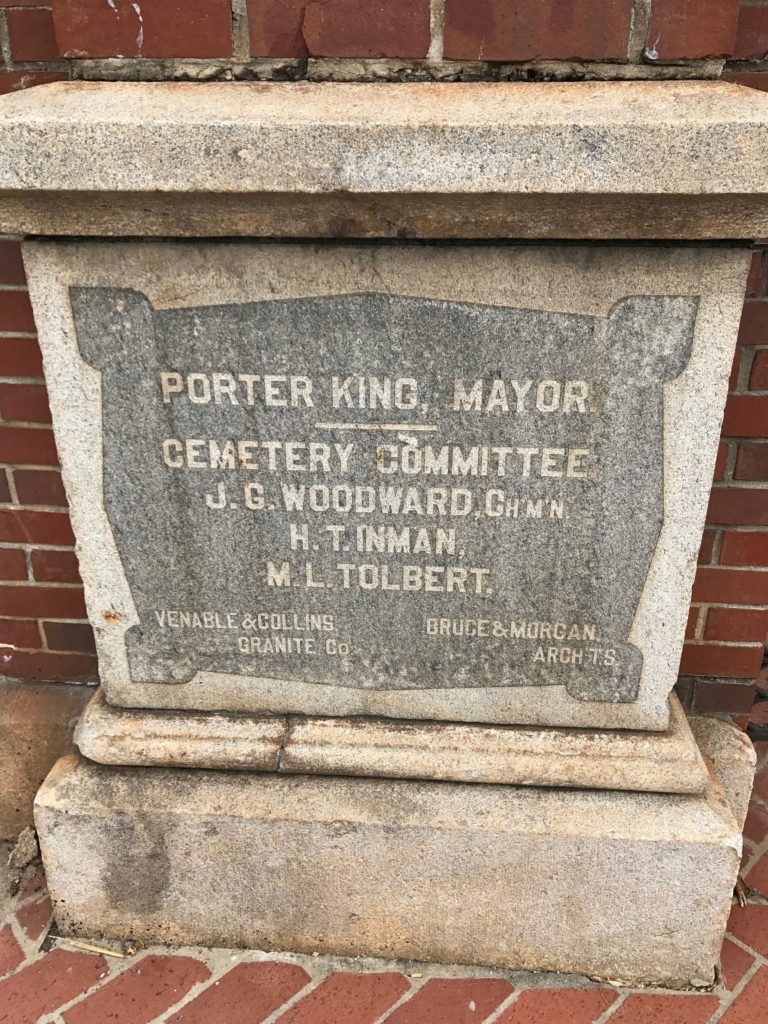

- City of Decatur Cemetery

- Resaca Cemetery

- Wirz Monument (Andersonville)

- East Atlanta

- Atkins Park

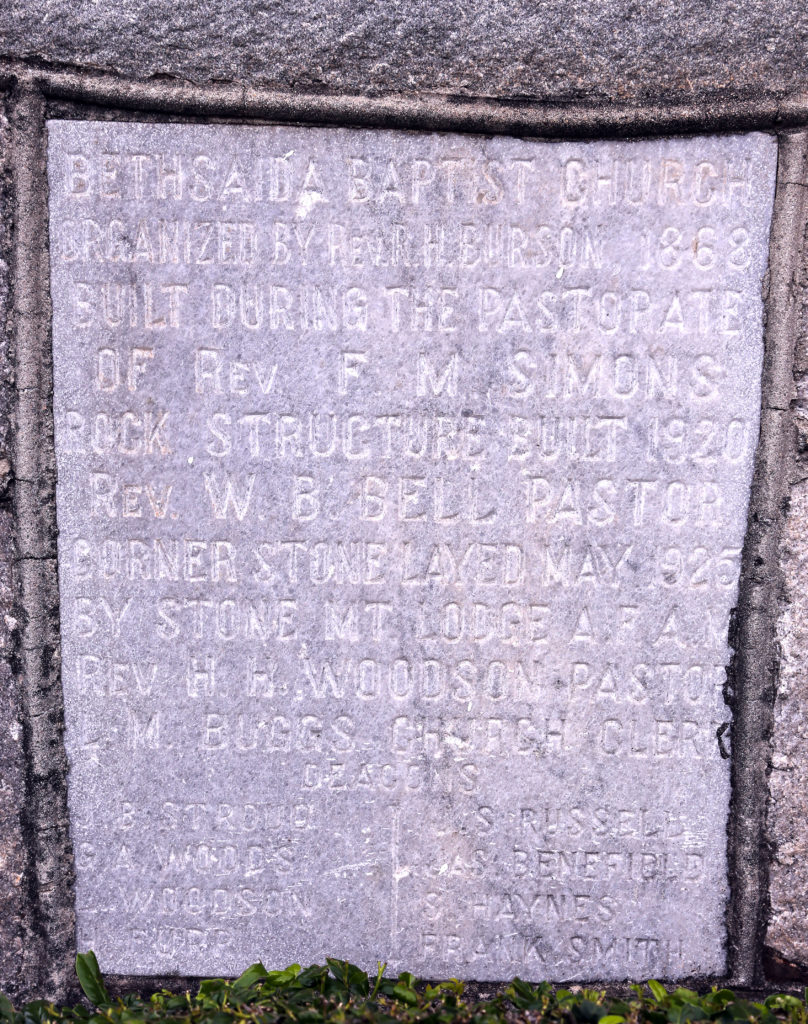

- Bethsadia Baptist Church

- Oglethorpe University

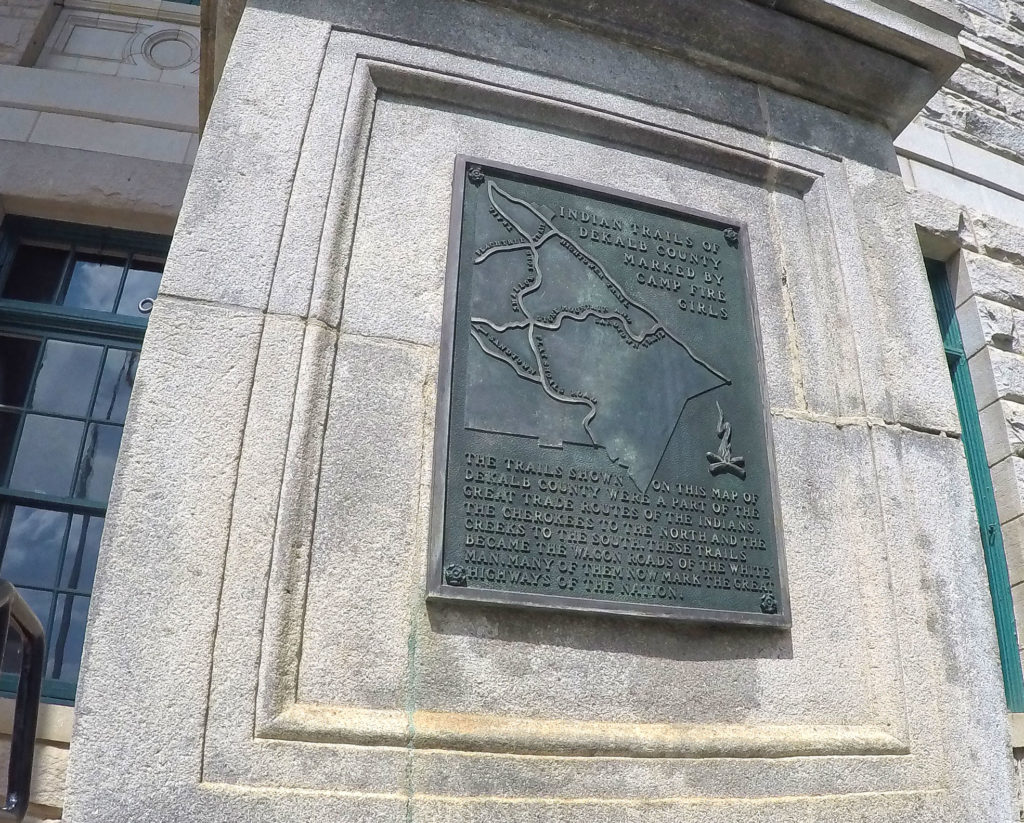

- Baron Dekalb marker (Decatur)

- H.M. Patterson undertaker parlors (10th St.)

- Dekalb County Courthouse

- Federal Reserve Bank

- First United Methodist Church

- Fort Benning

- Fulton Co. Courthouse

- Georgia State Capitol Building

- Inman Park Church

- J.M.Tull Building

- Manuel’s Tavern

- The Masquerade

- National Pencil Company (now site of Sam Nunn Atlanta Federal Center)

- City of Pine Lake

- Coan Park

- East Lake

- Decatur

- Georgia Tech

- Inman Park UMC

- Jonesboro Train Depot

- DuBignon residence

- North Avenue Presbyterian Church

- Oakland Cemetery

- Piedmont Park

- Rhodes Hall

- St. John's Lutheran Church

- St. Phillip AME Church

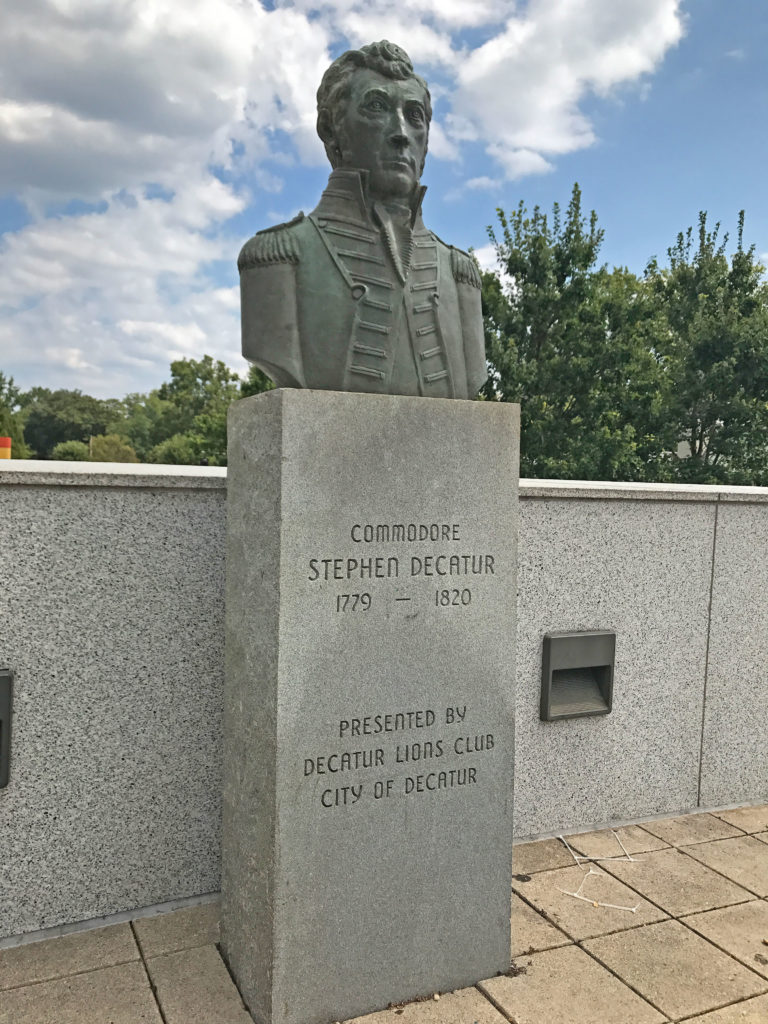

- Stephen Decatur memorial

- Underground Atlanta

- Westview Cemetery

- Wrecking Bar

- Henry W. Grady statue base

- Highland School (now lofts)

- Stone Mountain Village

- King Memorial Church (Kirkwood)

- Clark Atlanta University

- Stone Mountain Train Depot

- The Jane

- St. Mark United Methodist

Some Historic Background

In 1884, the Ohio contracting firm of Miles & Horn came to Atlanta to build an impressive capitol building, and in 1886 they bought a controlling interest in the Stone Mountain Granite and Railway Company and foresaw that millions of dollars to be made with the “inexhaustible” supply of granite and marble.

[Atlanta Constitution; 03/21/1886; “A Mountain of Granite”]

By July 1887, the Venable Brothers retired their shares of the Southern Granite Company and took sole ownership of Stone Mountain in a trade with Miles & Horn.

[Atlanta Constitution; 07/18/1887; “There Has Been a Change: The Southern Granite Company Changes Hands”]

In an intriguing coincidence, but a few weeks later, C.D. Horn of Miles & Horn was accidentally shot dead on August 8, 1887 inside a room at the second Kimball House by A.B. F. “Bud” Veal of Stone Mountain, as he tried to break up a longstanding fight between Veal and Sam Venable. Veal also had a quarry, and Stone Mountain has a Veal St., as well as a Venable Street in Shermantown.

[Atlanta Constitution; 08/08/1887; “C.D. Horn Killed”]

[Atlanta Constitution; 08/09/1887; “Day After the Deed”]

By 1894, the Venable Brothers had secured a clear monopoly of Georgia’s granite industry. The newspaper reported that “the transaction places the Venables in practical control of all of the granite properties of this section of the state. They will now have considerable less opposition in the field and have enough granite to run great quarries for years to come. The property is inexhaustible.”

[Atlanta Constitution; 3/14/1894; “Big Granite Deal”]

And the Venables continued to bid on every government contract to supply Stone Mountain’s “fireproof” granite for practically every building opportunity in Atlanta, including this impassioned pitch to use it on the 10-story building they wished to erect on the site of Atlanta’s previous Georgia State Capitol Building:

“What about the vaults for the papers?” asked Mr. Inman.

“The building,” said Sam Venable, “will be fireproof. It will be built of Stone Mountain granite and steel…”

“Atlanta,” said Mr. W.H. Venable, “has papers that could never be replaced if they were destroyed by fire…”

[Atlanta Constitution; 02/26/1896; “Ten Stories High”]

The Kimball Opera House was home to the state legislature in Atlanta from 1869 until 1889 (the state purchased the building in 1870). The building eventually did become the Hotel Venable (also referred to as The Granite Hotel), and later, the same building became the National Pencil Company, the infamous site of thirteen year-old Mary Phagan's murder on April 26, 1913, located at 37-41 South Forsyth Street in downtown Atlanta (today it's where the Sam Nunn Atlanta Federal Center is located downtown). Her murder, pinned on a Jewish factory manager, Leo Frank, spurred a group of white men initially calling themselves the Knights of Mary Phagan, many of them prominent politicians, to burn crosses on top of Stone Mountain in November 1915 and to rename themselves the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. Many of these same men had participated in the lynching of Leo Frank in Marietta, GA just weeks before on August 17, 1915.

Why It Matters | Atlanta is the Mountain

Stone Mountain granite literally helped to build Atlanta, which anyone can see throughout Metro Atlanta, even along the Atlanta BeltLine corridor in many places. A great deal of Atlanta is structurally linked with Stone Mountain (images are below) which, even if only symbolically, almost implicates it—and the whole state—in whatever has gone on there and what will happen next there. I am reminded of the stunning example of how bricks matter when talking about Atlanta's history. The other day I saw someone's mother post a photo to Facebook of herself at Houston's restaurant on Peachtree Street; she stood next to some of the bricks from the original Loew's Grand Theatre, where Gone With the Wind premiered (it's now the Georgia Pacific Building) that were used to build the restaurant, and I cringed inside, knowing some of the history of the Chattahoochee Brick Company.

Most of us are familiar with the events at the mountain beginning in 1915, when it became the 20th Century rebirth place of the KKK. It was permanently branded with a Civil War carving that took decades and multiple carvers to finish by 1970, and it was turned into a legally protected Confederate monument by legislators. It overcame its past long enough to host some of the 1996 Summer Olympic Games, and in 1998, Herschend Family Entertainment (aka Silver Dollar City) signed a 50-year lease to manage the park's attractions. Regular readers of I Am the Mountain know that I personally consider the mountain to be a natural formation that’s been held hostage in a theme park since 1923 [Edited to add: longer than that!]. A theme park is an unfit gatekeeper for history. I am frequently critical of how natural resources are used there and am disappointed that they do not offer recycling within the park. Nor should park pass payments support Confederate monuments. Yet I love climbing the mountain and meeting the variety of people there.

Stone Mountain Park recently permitted white supremacists to hold a rally on 4/23/16, less than a year after 21-year-old Dylann Roof —who posed with white supremacist symbols like the Confederate flag and visited Confederate monuments — murdered nine innocent black churchgoers at Mother Emanuel in Charleston on June 17, 2015. Stone Mountain Park often tolerates situations where Confederate symbols at Stone Mountain serve as a beacon of hate for racists, such as the group of alt-right racists I encountered on top of the mountain on 9/10/16. While not an official state park, Stone Mountain Park is under the jurisdiction of the state of Georgia and the Stone Mountain Memorial Association, and Herschend Family Entertainment manages its attractions.

"With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood." — Dr. Martin Luther. King, Jr., "I Have a Dream"

Today Stone Mountain is a diverse, multicultural area, with many refugees resettled there and in neighboring communities like Clarkston, and most of the racists and neo-Confederates who organize their pathetic, sparsely attended rallies in Stone Mountain Park actually do not even live in Metro Atlanta but drive in from small rural towns and gravitate to Stone Mountain because they still regard it as a symbol of white supremacy from the days when the Klan officially held sway there, from approximately 1915 to 1958.

I do not know if Stone Mountain Park will ever fully be able to rebrand itself from once being synonymous with the Klan without changing the very laws that currently protect the Confederate symbols there that continue to speak to racists. The park also must change the ways it teaches history and presents its past (i.e. it barely does), even its most difficult chapters. This is one of the primary reasons I choose to highlight people from all over the world—of all races, walks of life, abilities, and religious faiths at I Am the Mountain — who, despite the odious Confederate symbols, are drawn to the mountain and have in a sense already reclaimed it from its traumatic history for themselves. They hike it for countless positive reasons and use it for recreation and general well-being now more than ever.

I think it's important to show who is visiting and climbing Stone Mountain outside of its tired Confederate context, especially since Stone Mountain Park boasts millions of visitors a year from all over the world. I celebrate diversity and different cultures, and I think it's imperative that we continue to talk about race at a former bastion of white supremacy. Perhaps illustrating how "Atlanta is the Mountain" is one way to help more relate to the fact that what happens at Stone Mountain reflects on Atlanta and the entire state.