I think often about what it means to be free. To truly feel free. To experience free thought and to exercise free expression. To live and to pursue happiness freely. To be creative and original and free of inner (and definitely outward) censorship triggered by a hostile environment. This year I found it somewhat hollow to celebrate Independence Day when so very many Americans, myself included, have been feeling downright worried and anxious, such that it would seem the liberty bell does not toll for thee. “We’re better than this,” that bell’s been clanging on the hour in my belfry since November. I often steady myself, as if inside a doorframe during an earthquake, with whatever wisdom and poetry from the ages and good deeds and sound judgement and kindness of the day I can, conjuring beauty and reason the best I know how to nourish my addled spirit. I wear these treasures like a chain of garlic around my neck to ward off tyrants that would do everything in their power to spill blood and break my spirit and yours, mankind — and then leave us like piles of divided, disoriented human waste with not so much as affordable healthcare with which to tend our wounds and make ourselves whole again.

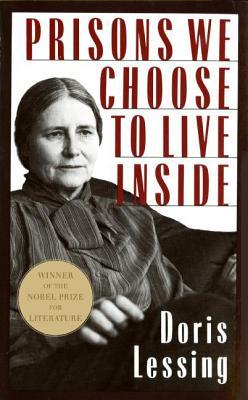

One of my go-to re-reads when I’m feeling bleak about world affairs is a brief tome by Nobel Prize winner Doris Lessing called Prisons We Choose to Live Inside. I open the slim volume of essays (if I remember right, intrigued by the title, I selected it off the used cart outside of the bygone Book Court in Brooklyn), and it’s as if she’s in the room conversing with me over coffee. If I was at all feeling imprisoned by fear in that room before, her words gave me a furlough. Lessing is such a fascinating thinker, and much of her writing, certainly hugely influenced by seeing the horrors of South African apartheid up close, serves as a powerful reminder to resist reverting to barbarism and acts of cruelty, brutality, and plain old stupidity whenever there’s a power surge inviting back in our savage past. Beware the waves of nationalism, calls to war, and old-fashioned propaganda that threaten to estrange you from your higher good nature, her words echo. Lessing challenges society to be held accountable for “knowing more about ourselves than people did in the past….to remember the truth, and not the sentimentalities with which we all shield ourselves from the horrors of which we are capable.” Sift through “the dustbin of history” to retrieve reason and sanity, especially whenever civilization suffers a violent reversal like we’ve recently been experiencing in America.

One of my go-to re-reads when I’m feeling bleak about world affairs is a brief tome by Nobel Prize winner Doris Lessing called Prisons We Choose to Live Inside. I open the slim volume of essays (if I remember right, intrigued by the title, I selected it off the used cart outside of the bygone Book Court in Brooklyn), and it’s as if she’s in the room conversing with me over coffee. If I was at all feeling imprisoned by fear in that room before, her words gave me a furlough. Lessing is such a fascinating thinker, and much of her writing, certainly hugely influenced by seeing the horrors of South African apartheid up close, serves as a powerful reminder to resist reverting to barbarism and acts of cruelty, brutality, and plain old stupidity whenever there’s a power surge inviting back in our savage past. Beware the waves of nationalism, calls to war, and old-fashioned propaganda that threaten to estrange you from your higher good nature, her words echo. Lessing challenges society to be held accountable for “knowing more about ourselves than people did in the past….to remember the truth, and not the sentimentalities with which we all shield ourselves from the horrors of which we are capable.” Sift through “the dustbin of history” to retrieve reason and sanity, especially whenever civilization suffers a violent reversal like we’ve recently been experiencing in America.

If nothing else, set yourself free.

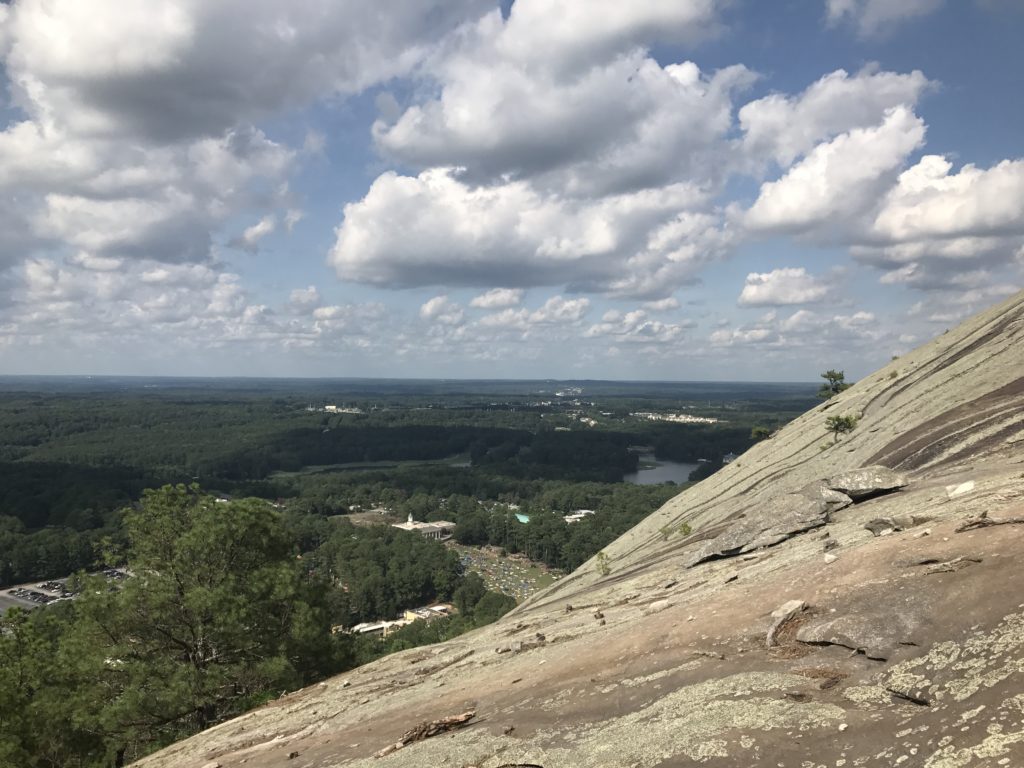

I do not forget, though, that 50 years ago Georgia swore in segregationist Lester Maddox as its governor, and 50 years ago yesterday marked Stone Mountain Park's first Fantastic Fourth celebration (next year marks 60 years since the State of Georgia took the mountain into its possession). Even on a good day, when I talk to so many wonderful people from all over the world on the mountaintop, it is still quite tough to reconcile (and I can't do it alone) that the park, which officially opened two years before—chillingly on April 14, 1965, the very centennial of Lincoln's assassination—did so, and with millions of dollars, in direct opposition to the Civil Rights Movement sweeping the nation then. One can still make out a carving on the mountain that reads "Lester for Gov '67." That one of this nation's biggest Independence Day celebrations ever took place at a Confederate monument in the first place (where I believe that in order to get hired you must first agree to work on the Fourth of July) boggles the mind, since the Confederacy wanted to secede from the U.S., and its proponents and neo-Confederate offshoots are still fomenting most of the anti-government sentiment in this country today. Consider also that former Governor Zell Miller was Lester Maddox's Chief of Staff at the time, and fast forward to the early 1990s when Miller served on the board of the Stone Mountain Memorial Association and was instrumental in passing the very laws that currently protect the Confederate flags and the carving at Stone Mountain Park to this day.

For me it is unsettling that the letters U.S.A. are projected by lasers during a laser show, added in 1983, over the carving of three Confederate generals—and it's not a show I go to. It's also one of the main reasons why I still will not pay for a parking pass at this privately operated park (on state land) until the park operates with greater transparency and does not require parkgoers' fees to go toward the vague end of "maintaining a Confederate monument." Many people are likely not making the connection that the money they give to the park contributes in at least some part to upholding a Confederate monument. How unfair to consumers and, really, how perverse this is if you do not actually support the perpetuation of institutionalized racism, which is essentially what Confederate monuments symbolize. Who is truly profiting from all of that patriotism over there today? It's a sincere question. People deserve more fair options to access the mountain. I have written more about it before.

For me, knowing the park opened on the centennial of Lincoln's assassination makes it all the more cringeworthy to say the least seeing the Confederate flags at the base of the walk-up trail flying alongside the American flag. These Confederate flags, all versions of Georgia's past and current flag, often fly at half-mast, such as on Memorial Day. Here they were at half-mast on June 11th for a fallen Gwinnett County solider, Etienne J. Murphy.

Speaking of the American flag, here's a sweet recording of five year-old Aurora and her new six year-old buddy saying the Pledge of Allegiance to the United States on 9/10/16, the very same day that I would later encounter alt-right racists on top of the mountain. 🇺🇸