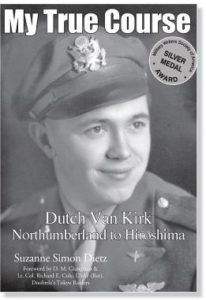

It really blew my mind a little when I first learned back in 2014 that Theodore “Dutch” Van Kirk, the last surviving member of the crew of the Enola Gay, which dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima (and three days later a different crew bombed Nagasaki), had been living so close to the mountain in a retirement community called Park Springs in Stone Mountain, GA, when he died at the age of 93 in 2014. The shadow of Stone Mountain actually falls on Parks Springs in the evenings, full moons often rise above it, and it's in a perfect position at sunrise. A few years ago I wrote about another retirement community, The View, that was being built at the time near the mountain in the Shermantown district of Stone Mountain Village. Van Kirk's late wife, Imogene, had passed two years prior at age 90, and she had resided at a different senior living community nearby, Sunrise at Five Forks. They had children living in Lawrenceville, GA and Elk Grove, California and numerous grandchildren and great grandchildren. Here (and below) is a video of "Dutch" Von Kirk talking about that mission.

It really blew my mind a little when I first learned back in 2014 that Theodore “Dutch” Van Kirk, the last surviving member of the crew of the Enola Gay, which dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima (and three days later a different crew bombed Nagasaki), had been living so close to the mountain in a retirement community called Park Springs in Stone Mountain, GA, when he died at the age of 93 in 2014. The shadow of Stone Mountain actually falls on Parks Springs in the evenings, full moons often rise above it, and it's in a perfect position at sunrise. A few years ago I wrote about another retirement community, The View, that was being built at the time near the mountain in the Shermantown district of Stone Mountain Village. Van Kirk's late wife, Imogene, had passed two years prior at age 90, and she had resided at a different senior living community nearby, Sunrise at Five Forks. They had children living in Lawrenceville, GA and Elk Grove, California and numerous grandchildren and great grandchildren. Here (and below) is a video of "Dutch" Von Kirk talking about that mission.

By now conditioned to war’s inevitability, I’ll still never be at peace with it as a necessity. So I often need reminding when days like today roll around, this the 72nd anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, why such a devastating and secret mission took place and again why those charged to carry it out are considered heroes when it was so catastrophic. The doublethink for me began at an early age, one minute seeing black and white images of Japanese citizens running for their lives through a radioactive black rain of nuclear fallout, and the next suddenly shooting fireworks on the Fourth of July, swallowing such horror, and suspending compassion for them long enough to revere those who dropped Big Boy and Fat Man on them, killing tens of thousands including at least 23 American POWs, so as to protect me and you and our country.

By now conditioned to war’s inevitability, I’ll still never be at peace with it as a necessity. So I often need reminding when days like today roll around, this the 72nd anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, why such a devastating and secret mission took place and again why those charged to carry it out are considered heroes when it was so catastrophic. The doublethink for me began at an early age, one minute seeing black and white images of Japanese citizens running for their lives through a radioactive black rain of nuclear fallout, and the next suddenly shooting fireworks on the Fourth of July, swallowing such horror, and suspending compassion for them long enough to revere those who dropped Big Boy and Fat Man on them, killing tens of thousands including at least 23 American POWs, so as to protect me and you and our country.

With nuclear missile threats ever more in the news right now and power struggles intensifying with North Korea and Russia (no need to stop there), I continue to search for explanations and understanding of the past invasion of Japan for insight into what may be ahead. I understand that America is not alone in marking time and the tempo of national allegiance by war. In fact, the urban and natural infrastructures of many American cities are dotted with historic forts, war markers, statuary, and museums devoted to past wars. Many streets, buildings, mountains, and lakes have often been named, for better or worse, after war figures, so it's no wonder that the American narrative sometimes feels so distinctly military and has often eclipsed other important histories of its people.

“What struck me as I began to study history was how nationalist fervor―inculcated from childhood on by pledges of allegiance, national anthems, flags waving and rhetoric blowing―permeated the educational systems of all countries, including our own. I wonder now how the foreign policies of the United States would look if we wiped out the national boundaries of the world, at least in our minds, and thought of all children everywhere as our own. Then we could never drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, or napalm on Vietnam, or wage war anywhere, because wars, especially in our time, are always wars against children, indeed our children.” ―Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States

A few years ago I also asked Dallas-based historian Farris Rookstool, III, who personally knew Van Kirk, to explain how someone that dropped a nuclear bomb on innocent people could be a hero:

"I have many people who I admire and some are heroes too. When I referred to Theodore 'Dutch' Van Kirk as an American hero, I referred to him as such based on the fact that he and his crew were tasked with doing something that had never been done before and that was dropping an Atomic Bomb from an airplane. He was recruited for his secret mission and wasn't told of the mission by Col. Paul Tibbets. They trained to fly the B-29 and made practice runs maneuvering the airplane on steep angles to prepare for moving away from the blast. While I am not a proponent of war, nor the use of nuclear weaponry, it was something that brought an end to WWII. Dutch said he never wanted to see nuclear weapons used again. When a soldier is called by his country to perform a life threatening task that runs great risk of failure and perhaps death and performs it with great success that saved thousands of American lives, I consider them a hero. Their mission could have resulted in great tragedy and resulted in more loss of life in the war. I knew almost the entire crew of the Enola Gay and cannot imagine the responsibility they had delivering a weapon to their target over enemy territory not knowing if they would perish in the blast as well. I hope this short little explanation helps to understand my reasoning for calling him an American hero." — Farris Rookstool, III, historian and award-winning filmmaker contributor to in The Day Kennedy Died: Fifty Years Later wrote the foreword to Oswald and I, and was even a ghostwriter for a chapter of Brad Meltzer's Decoded.

UPDATED 8/06/18 —

Today I noticed a similar story on NPR about the last surviving crew member of the lesser know warplane involved in the bombing of Hiroshima, Necessary Evil.

Two photos courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Two photos courtesy Wikimedia Commons