So many defenders of Confederate monuments insist we should place great honor on the Confederate soldiers who fought to protect the institution of slavery and spilled blood in an effort to secede from the United States of America. Some of them even call the carving of three Confederate generals on Stone Mountain art, claiming it's their heritage, yet they continue to ignore and neglect so many others' heritage, others whose blood was also shed into the ground right beneath their feet: the graves of enslaved people and their descendant — or worse, the absence of any markers that they ever existed. This country's own president even constantly baits his followers and champions of Confederate monuments: "They're trying to take away our culture. They are trying to take away our history." They will likely be able to tell you where all of the Confederate monuments and markers in Georgia are located, but very few can say where those who were enslaved are buried, the very people that worked the sprawling corn, cotton, and tobacco plantations and dairy farms in communities like Stone Mountain. While many of the graves of the sons and daughters of the enslaved did manage to find their rightful way into local city cemeteries, the condition of those graves and scarcity of records, depending upon the cemetery, still often reflect an inequality in death as those black Americans interred so frequently suffered in life. Such is what I found to be the case in the Stone Mountain City Cemetery when I went looking for the grave of Charlie C. Gholston in the African-American section of the historic cemetery. Unequal in death as in life cried out many broken headstones, as did the ones nearly swallowed up by the dirt or, in one case, overtaken by a nearby oak.

Charlie Gholston has led me on quite a journey over the summer. Not long after discovering his 90 year-old carving at the base of the Confederate flag terrace at Stone Mountain, I began looking into his life, and likely because this particular carving looked so much like a grave marker, I wanted to locate this former African-American air driller's grave (even if to rule out that the one at the mountain was not in fact a tomb). I first called the historic Haugabrooks Funeral Home listed in the 1938 “colored” obits section of the Atlanta Constitution. They could not provide any information, but since I mentioned Gholston and his family had been listed in census reports for Shermantown, the historic black community at the base of the mountain which supplied so much labor to the quarries and the railroads, the gracious and helpful employee there connected me via a three-way call to Gloria Brown, an older Shermantown native and community leader who might remember the Gholstons. Brown was inducted in recent years as one of the city’s “Granite Sentinels” (also the title of town resident George Coletti’s fiction book), and she proudly told me that her daughter was the first black cheerleader at the Victoria Maddox Simmons equalization school erected in 1956 in Shermantown (the property was razed in recent decades and is now the Mountain View senior living community). I quickly told her what basics I knew of Charlie Gholston and his parents, Augustus and Lucinda, but they didn't jog any memories for her, and she suggested that Charlie likely was not buried in one of the cemeteries associated with the historic churches in Shermantown, like Bethsadia Baptist Church, as she intimated those burial grounds came about later than Charlie’s death in 1938. So she suggested I look in the African-American section of the Stone Mountain City Cemetery.

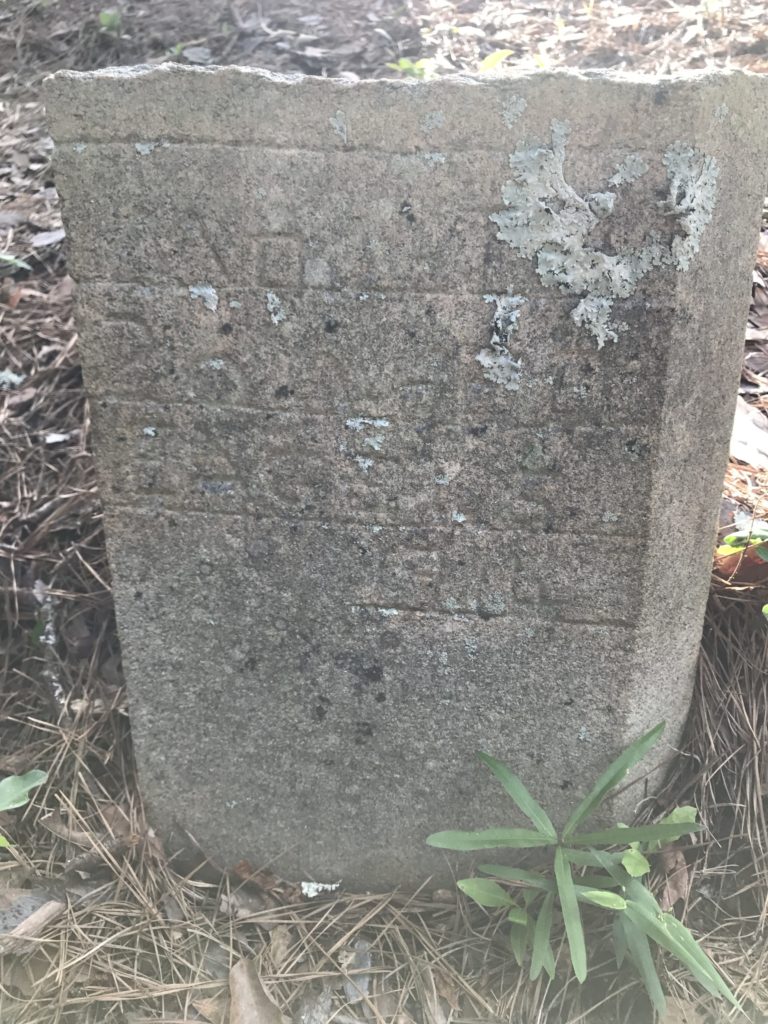

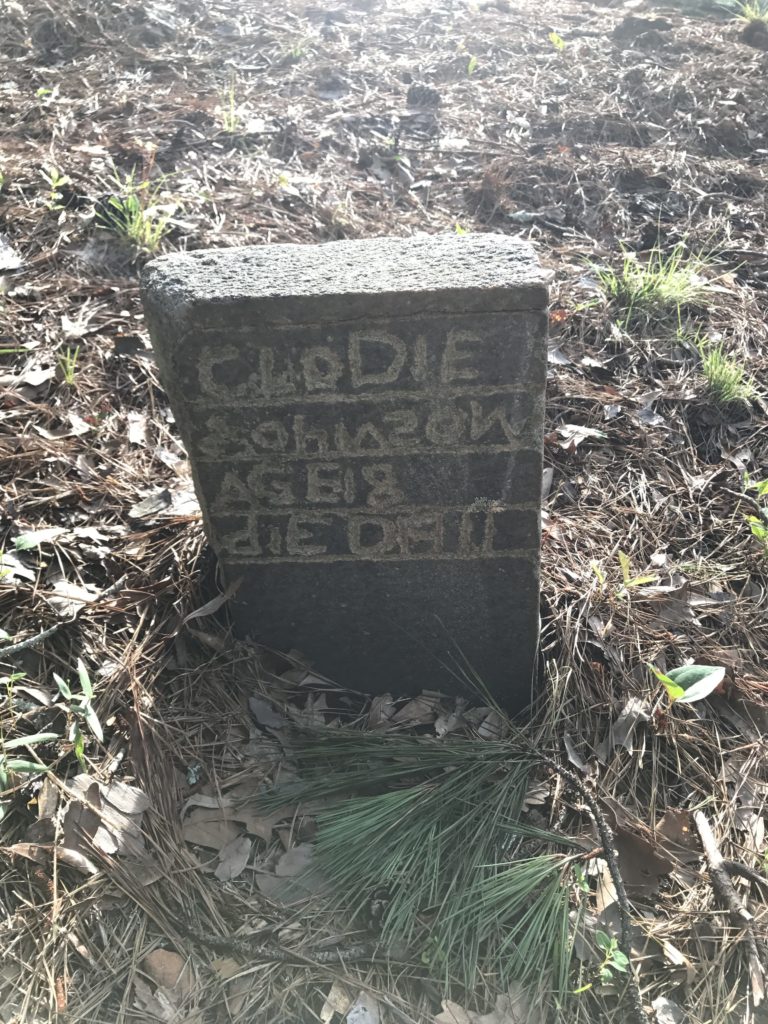

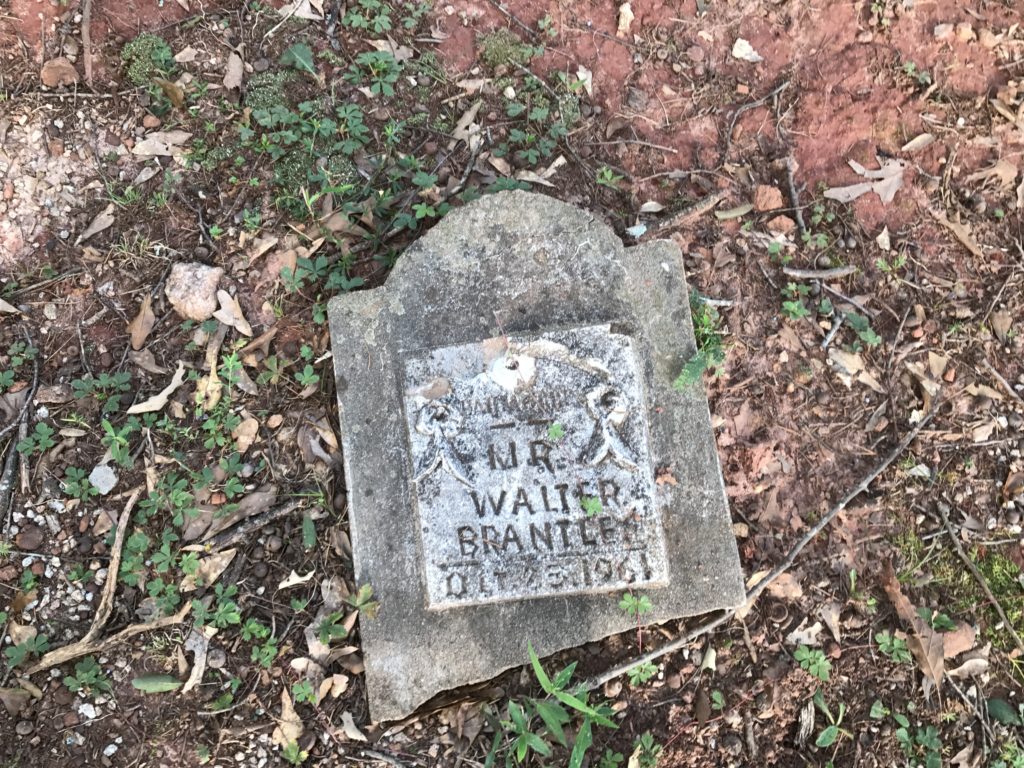

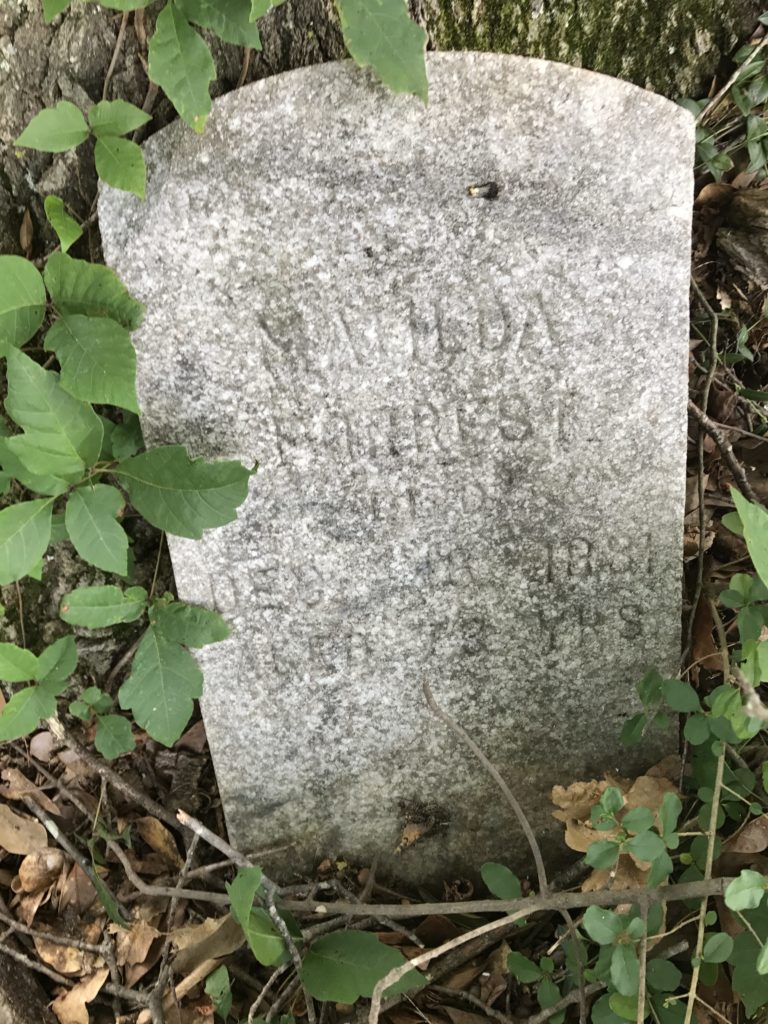

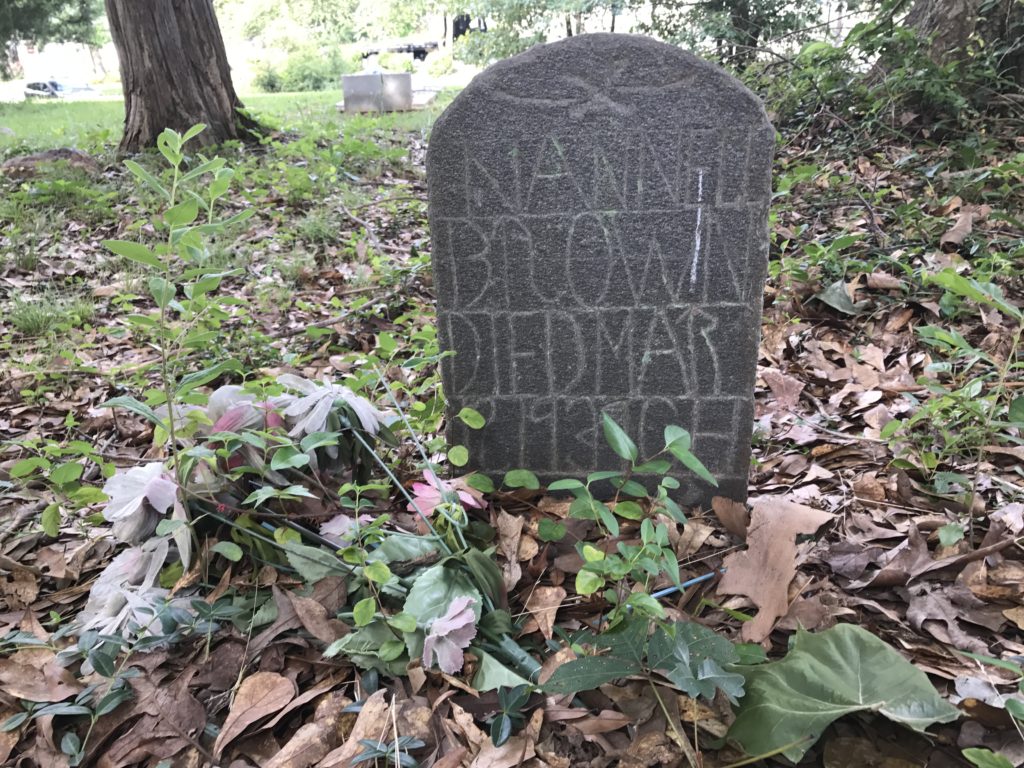

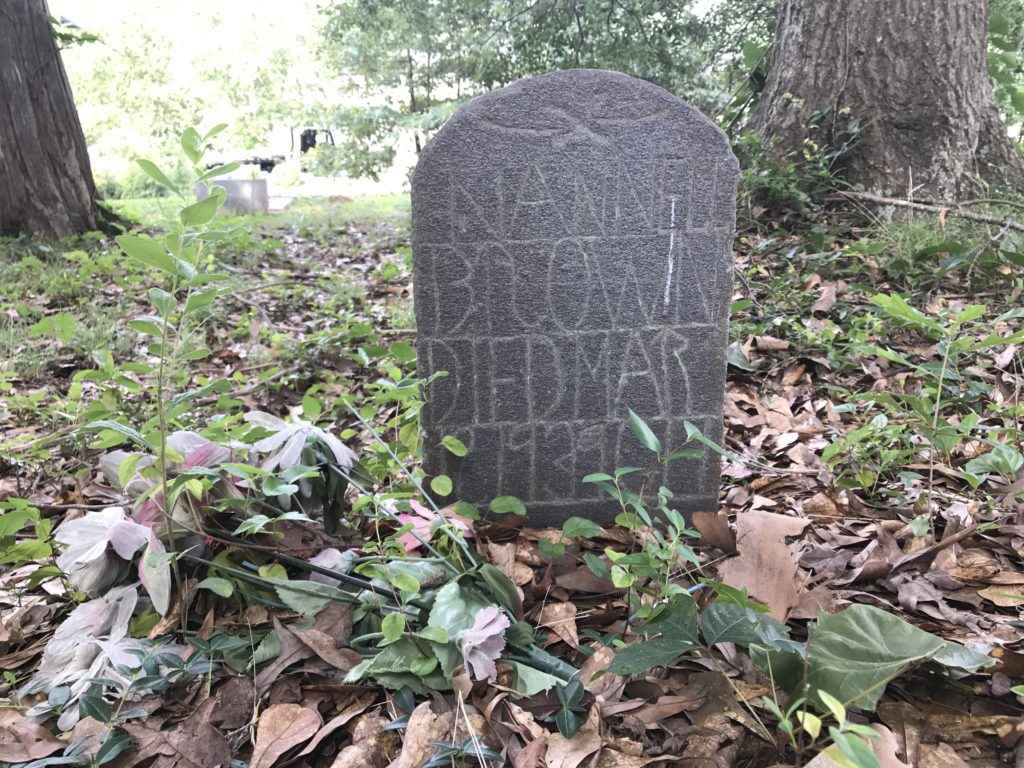

I first visited the Stone Mountain City Cemetery in early June to look for Charlie’s grave and was instantly disheartened by the rundown condition of the historic African-American section of the cemetery on the eastern side of the grounds, especially in contrast to the well-kept plots of the town’s prominent citizens and the celebrated Confederate soldiers there, even a secessionist signer from Dekalb County, G.K. Smith. The city extols particular reverence upon the bulging plot of George Pressley Trout, a Civil War soldier supposedly buried with his horse. Even the rows of white Confederate markers at the cemetery's E. Ponce de Leon & Main St. entrance commemorating the unknown dead Confederate soldiers (beneath which are no actual bodies) are better cared for than the graves of black citizens (beneath which are actual bodies).

I first visited the Stone Mountain City Cemetery in early June to look for Charlie’s grave and was instantly disheartened by the rundown condition of the historic African-American section of the cemetery on the eastern side of the grounds, especially in contrast to the well-kept plots of the town’s prominent citizens and the celebrated Confederate soldiers there, even a secessionist signer from Dekalb County, G.K. Smith. The city extols particular reverence upon the bulging plot of George Pressley Trout, a Civil War soldier supposedly buried with his horse. Even the rows of white Confederate markers at the cemetery's E. Ponce de Leon & Main St. entrance commemorating the unknown dead Confederate soldiers (beneath which are no actual bodies) are better cared for than the graves of black citizens (beneath which are actual bodies).

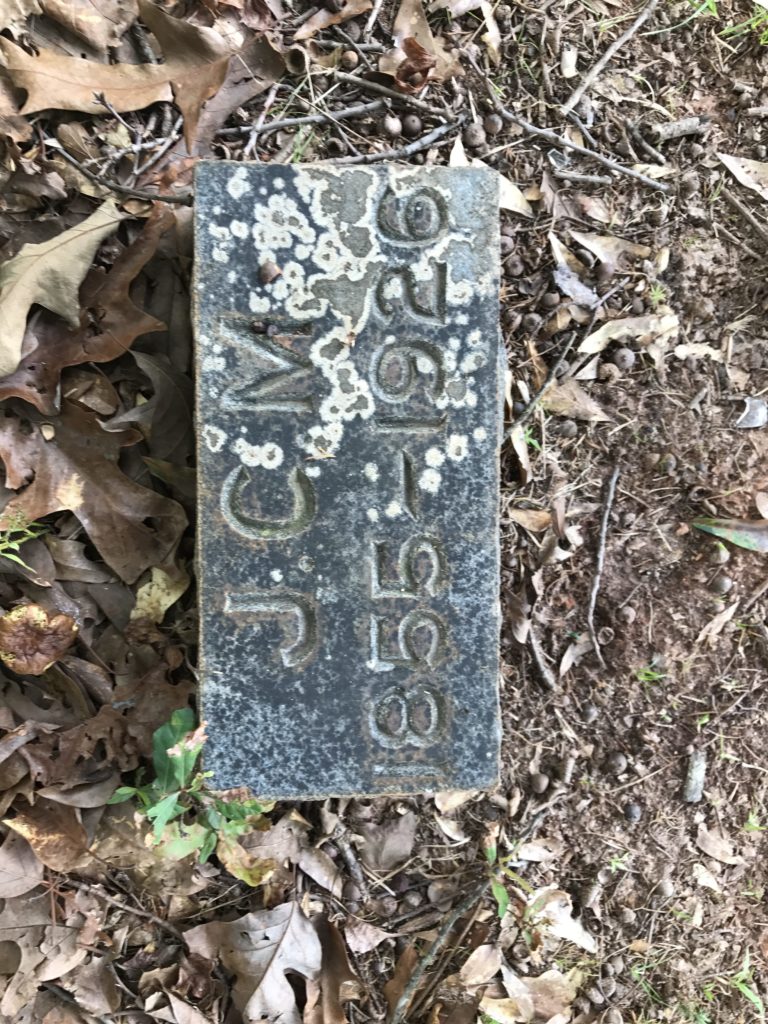

I called Gloria Brown again and expressed surprise and disappointment at how untended, even broken in half and illegible, so many of the headstones in the African-American section of the cemetery were and mentioned that I’d still not found Charlie’s grave. She said she had to go to a doctor’s appointment, and that's the last we spoke. When I again returned to the the African-American section of the city cemetery in early July, I was taken aback to suddenly spot a marker resting above the ground that seemed to read “Gholston." And yet, it didn't appear in the least overtaken by earth and time like the surrounding headstones. Sure, maybe I missed it the first time, I thought, but I had been pretty thorough that day in June and have felt unsettled about it since and am not convinced it's a marker for Gholston.

A few months ago, with the help of a grant, the City of Stone Mountain completed exterior renovations of the historic train depot in the center of the village for future use as its visitors center (interior renovations are still underway), which is currently housed in a red train caboose near the entrance to THE PATH. The Stone Mountain Downtown Development Authority, which is overseeing the train depot renovations, also regularly draws revenue from movies filming in Stone Mountain Village (parking spaces are often blocked along Main St. to accommodate studios and film crews when a movie's in town). Another recent ribbon-cutting ceremony took place in the Village of Stone Mountain this month for the renovation of another historic building on Main Street by C.D. Moody Construction out of Lithonia, GA. Yet, it seems that a city so synonymous with the contentious Confederate carving on Stone Mountain, and which has based its identity on a Confederate "brand" for so long, should not only focus on development but also upon restoring some dignity to the graves of its buried black citizens in the Stone Mountain City Cemetery. Also, is that an old slave cabin on Second Street in the back yard of Stone Mountain Manor? I often pass it on my way to the park, and I wrote the new owner of the bed-and-breakfast to ask for more information on it but have not heard back.

A few months ago, with the help of a grant, the City of Stone Mountain completed exterior renovations of the historic train depot in the center of the village for future use as its visitors center (interior renovations are still underway), which is currently housed in a red train caboose near the entrance to THE PATH. The Stone Mountain Downtown Development Authority, which is overseeing the train depot renovations, also regularly draws revenue from movies filming in Stone Mountain Village (parking spaces are often blocked along Main St. to accommodate studios and film crews when a movie's in town). Another recent ribbon-cutting ceremony took place in the Village of Stone Mountain this month for the renovation of another historic building on Main Street by C.D. Moody Construction out of Lithonia, GA. Yet, it seems that a city so synonymous with the contentious Confederate carving on Stone Mountain, and which has based its identity on a Confederate "brand" for so long, should not only focus on development but also upon restoring some dignity to the graves of its buried black citizens in the Stone Mountain City Cemetery. Also, is that an old slave cabin on Second Street in the back yard of Stone Mountain Manor? I often pass it on my way to the park, and I wrote the new owner of the bed-and-breakfast to ask for more information on it but have not heard back.

Georgia lawmakers approved more protections for Confederate monuments during the 2019 legislative session. Yet, history in Stone Mountain still often feels as neglected as the historic Johnson-Maddox-Goldsmith Cemetery on Memorial Drive in Stone Mountain looks. Many state politicians do next to nothing to teach, promote, and preserve local and regional history beyond the monotonous Lost Cause narrative. Consider even the bodies of some of Stone Mountain's first white settlers, such as Andrew Johnson, interred here next to a used car lot in a rundown shopping strip near the Village of Stone Mountain and Stone Mountain Park, not far from where I grew up.

Yes, while it is the city's responsibility to maintain its cemetery, care for neglected historic graves does often fall to family or concerned volunteers to keep the stones clean and repaired and to keep the deceased from being forgotten. For example, a group of volunteers came together in Lithonia a little over ten years ago to preserve the Flat Rock Cemetery, which had become overgrown and neglected. So many of those interred there had lived along Bruce Street (in a community similar to Shermantown) and worked in the quarries near Arabia Mountain during the time Arabia Mountain was still owned by the Venable brothers, which also simultaneously owned and quarried Stone Mountain and Pine Mountain. For many decades now, Arabia Mountain has been part of the Arabia Mountain National Heritage area, overseen by the Arabia Mountain Heritage Alliance . Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta also has an ongoing African-American Grounds Restoration Project, as do many communities that work together to preserve African-American heritage alongside other parts of their history. It's often long overdue work, and sadly, it sometimes comes too late. A distant descendant of Andrew Johnson's, who is widely regarded as Stone Mountain's founder, tried to restore some care and dignity to the Johnson-Maddox-Goldsmith Cemetery many decades ago, but it longs for more attention and preservation.

Discovering William Sheppard Family Cemetery

Discouraged as I was after visiting the Stone Mountain City Cemetery, I wasn't done looking for Charlie Gholston's grave and suddenly found myself in the unlikely position of talking with the great-grandson of former slaveholders in the Stone Mountain area, a colorful character who's lived in the Stone Mountain area his whole life and knows a great deal of its history — and, as it turns out, where many of the bodies are literally buried. Paul Bioust, 62, acts as the registered caretaker for the William Sheppard Family Cemetery, a small well-maintained family cemetery tucked within a quiet subdivision off of Fon Du Lac Drive, just past Pine Lake near Stone Mountain, and currently lives across the street from it on the last remaining undeveloped part of the old Sheppard Plantation on Rockbridge Rd., which, excepting acreage set aside for his home, is currently on the market for over a million dollars. His father Alfred's mother was Runnell Sheppard, and her father was John Sheppard, whose father was William Sheppard. Most of the "founding family" Sheppards from the Stone Mountain area, which owned plantations and dairies, are buried in the cemetery at Mountain View Baptist Church off of Redan Rd., but numerous others, including many unmarked graves, can be found in this smaller William Sheppard Family Cemetery. Freedom Middle School on South Hairston Rd. opened in January 2001 on the site of the former Sheppard Brothers Dairy Farm, sold off in the 1990s, and what were once tiny dairy houses can still be seen along S. Hairston. Worth noting is that his neighbors down the road on Rockbridge Rd. are the Yorubas of Atlanta.

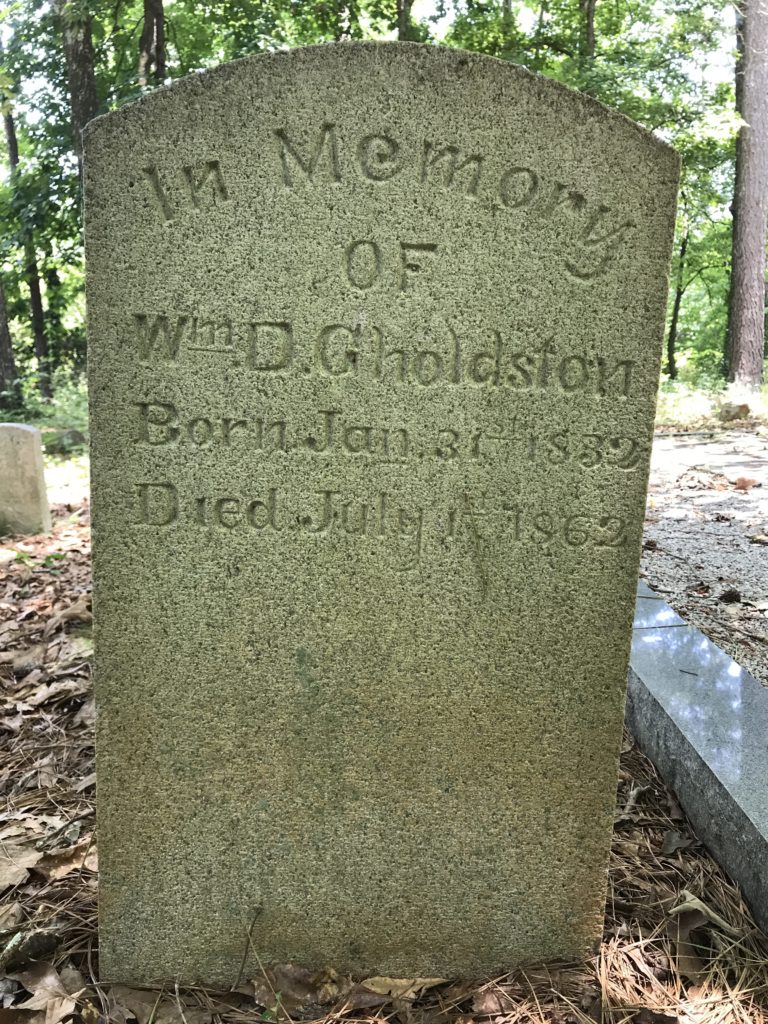

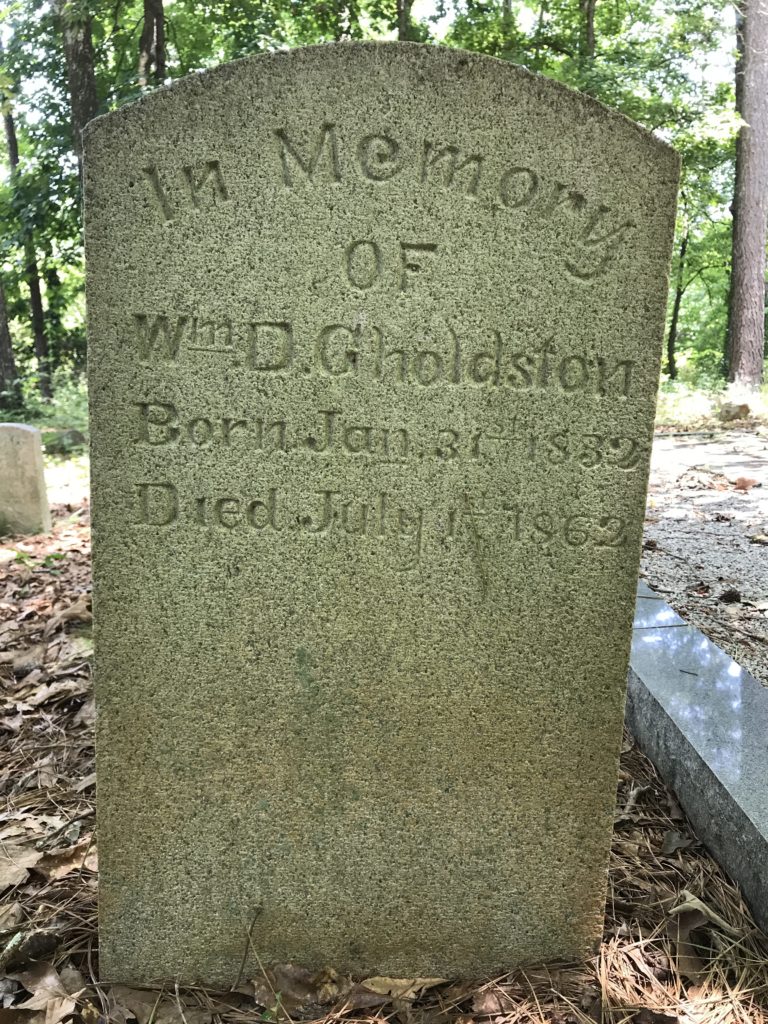

Research on Ancestry.com led me to this spot in the first place, as it indicated it was the final resting place of one W.D. Gholston, who died in the Civil War in 1862. My immediate thought was that Charlie Gholston or his father Augustus could somehow be connected to him since they shared a last name. I wondered, had the black descendants of the Gholstons living in Shermantown once been owned by the white descendants of William Dabney Gholston, who married Sarah Sheppard (who's also buried here)? Could Charlie also rest here, if he wasn't in the city cemetery? So many burning questions, but the cemetery was locked behind a tall barbed wire fence, which Paul later told me was to prevent vandalism and "goth" rituals, and as I explored its perimeter for an opening to possibly sneak through, I spied the lone slave grave of Ben Sheppard through the fence. I stopped cold in my tracks: BEN SHEPPARD, SLAVE. It was placed away from the main family headstones, and the word SLAVE so boldly dehumanizing took the place of personal sentiment like "he was loved by all and was somebody's child," but I was still glad that someone had at least cared enough to carve his name into that headstone and give him a proper burial. Because, as we know, untold numbers of enslaved women and men were not buried properly, much less with markers bearing their names on them, and to this day the news continues to report chilling discoveries of enslaved humans' remains, which are usually crudely unearthed during construction and development of subdivisions, highways, and shopping centers. I naturally wanted to know more about Ben Sheppard and the Sheppards overall.

FURTHER READING

Dekalb County, Georgia Historic Cemetery Index

Flat Rock Archives keeps African-American history alive

Reclaiming African American Cemeteries In Lithonia

Slave Cemetery Discovered in South

Histories Vanish Along With South's Cemeteries

Gone and almost forgotten — slave graves along I-75

Cemetery for former slaves goes unnoticed among Buckhead homes

In the shadow of luxury, a cemetery for former slaves, in ruins

University Of Georgia To Rebury Remains Unearthed During Construction

Memory Hill Cemetery's Slave Graves (Milledgeville, GA)

Oakland Cemetery African-American Grounds Restoration Project

Cemetery Dedicates Memorial for 1,100 Unmarked Graves of African-Americans (Gainesville, GA)

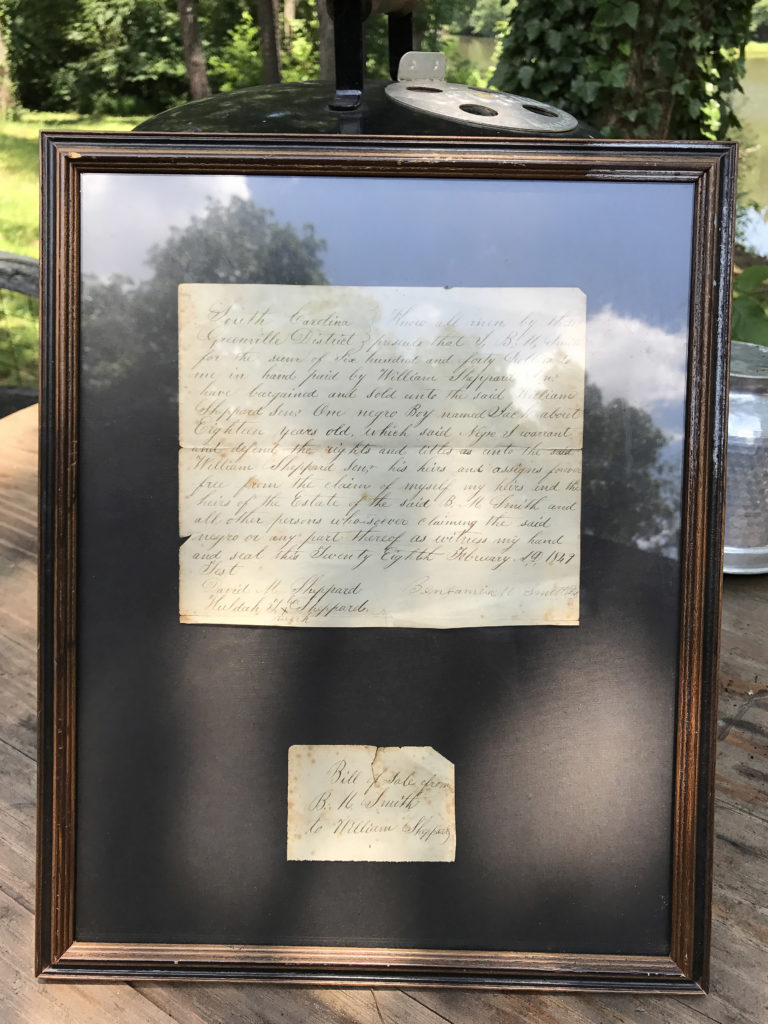

Increasingly determined to get a closer look at Ben Sheppard's grave and look for the Gholstons, I returned to the middle-class neighborhood and pulled up to a man outside doing yard work to ask if he might know how to access the cemetery. I’d knocked on doors a few days before with no luck, I told him. He pointed to a house up the street and suggested that the woman there had lived in the neighborhood a long time and might know more. No one answered when I rang her bell. But his recommendation to talk to the man that tended the cemetery was a game changer, because Paul Bioust is not only the registered caretaker, he is also related to the Sheppards. But I didn't know any of that, or that we're both graduates of Stone Mountain High, when I drove down his gravel driveway in July. I was so grateful that he made himself available to personally open the cemetery gates for me that afternoon and began to share some of his family history. I had never seen Confederate money or the absolutely heart-breaking bill of sale for an enslaved 18 year-old named Jack before that day. I also left with a binder of compiled Sheppard genealogy to study and a large fascinating 1915 map of Dekalb County detailing the names of landowners from that time.

Discovering David Mannon Sheppard Cemetery

I asked Paul about another small Sheppard Family cemetery I had read about on one of the Ancestry.com message boards, the David Mannon Shepard Family Cemetery off of Redan Road. I'd read it was overgrown and literally in the back yards of at least two homes on Autumn Hill Drive. And, while Paul is not the registered caretaker of it, and had not visited it in possibly decades, he offered to take me to see it. Ms. Dawes answered the door when we knocked at her home to let her know we would be going into her back yard to see the cemetery, and then Paul grabbed a machete from his truck and walked ahead of me whacking away the English ivy. I felt just as sad about these abandoned graves as I had for the untended graves in the African-American section of the Stone Mountain City Cemetery. As with the William Sheppard Family Cemetery, many of the descendants of those interred in the David Mannon Sheppard Cemetery are also buried at nearby Mountain View Baptist Church. Also, David and Huldah Sheppard have stones in the David Mannon Sheppard Cemetery but are actually buried at the church cemetery.

Discovering Martin's Crossing Graves

Later in the summer I learned of yet more abandoned graves in two different areas of the Martin's Crossing subdivision in Stone Mountain, also in residential back yards, likely graves of some of the other original settlers in the area, such as the Crowe and Smith-McElroy families. A long time ago, people often buried loved ones and slaves directly on their plantations and farms. As more time goes by, it would appear that land development does not always favor the dead or remember history. It's painful to consider how many more forgotten graves might still be out there along South Hairston, Sheppard, Elam, Redan, and Rowland Rd., and really wherever there were once vast acres of plantations.

Exploring More Historic Dekalb County Cemeteries

The Crowley Family Mausoleum on Memorial Drive in Avondale Estates, GA is quite a curiosity. It's tucked between Napa Auto Parts Store ("the parts store") and Walmart, where Avondale Mall used to be. As the grave markers are above ground, at least one local referred to it as "the cemetery in the sky." Many speculate that there are still unaccounted for graves in the surrounding undeveloped property currently listed for sale.

Imagine being interred in the shadow of a towering commercial billboard next Best Buy and Aldi and Cartridge World. I appreciate how a Tucker civic group listed the numerous small cemeteries of the town's founding families. It's easy to see how development has encroached upon many of these historic lots over time.

Founding Families of Tucker Self-Guided Cemetery Tour