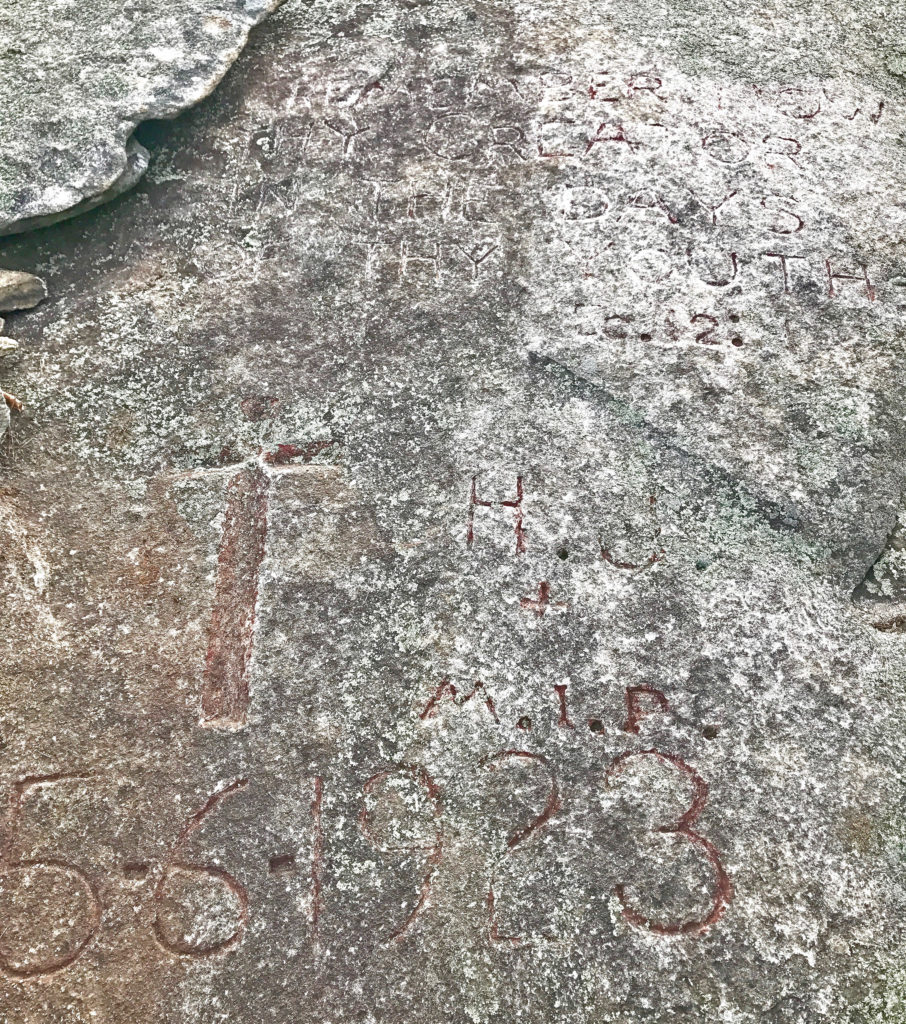

A couple of years ago, a friend pointed out a rather sizable engraving in a remote spot on top of Stone Mountain just above the copse of trees known to locals as Buzzards Roost, for the ubiquitous turkey vultures, and occasional American black vultures, that gracefully ride the hot air streams like wind surfers and roost there. We are among a small handful of people who catalog and try to interpret the carvings on the mountain and often compare findings, as the mountain itself has largely been left formally uninterpreted beyond the Confederate carving on its north face. At the time, “Remember Now Thy Creator In The Days of Thy Youth” just stood out as another curious example of Biblical verse chiseled into stone in various places along the walk-up trail, such as “Jesus Saved The Carpenters 1888” and “God So Loved.” The peppered rock-shield foliose lichen that proliferates on the monadnock, giving it its greenish tint, made the intriguing large inscription hard to read that first time, but I saw it again with fresh eyes yesterday and am now convinced it may present direct evidence of Klan activity on Stone Mountain, down to the very date it was carved: “Remember Now Thy Creator in The Days of Thy Youth Ec. 12:1 H.J. + M.I.P.* 5-6-1923.” [*M.I.P. may be M.I.N.]

I stood there studying the lettering, now bolder and more legible thanks to a reddish lichen, and suddenly had a flash of insight based on years of research; that the date “5-6-1923” was when the Second Era KKK celebrated its seventh anniversary on top of Stone Mountain (as they did the year before according to this 5-05-1921 article in the Atlanta-Constitution, as recounted in several Atlanta-Constitution articles leading up to and following the event. 1923 was also the year that sculptor Gutzon Borglum actually began the memorial carving on Stone Mountain, even though he first visited the mountain for design inspiration on August 16, 1915 — just one day before the kidnapping and lynching of Leo Frank in Marietta, GA. On May 5, 1923, the very day before this carving and the Klan anniversary festivities at the mountain, Margaret Mitchell had published her fanciful column “Hanging From Borglum’s Swing” in the Atlanta Sunday Magazine. It was also the year that the Venable Brothers issued the easement allowing the Klan to gather at Stone Mountain, which was later nullified shortly after the State of Georgia bought the property in 1958 and condemned the land. I was under the impression that such a nullification meant the hate group could never ever gather at the mountain again, so I was actually surprised when it was announced recently that the group had applied for a permit to burn a cross at Stone Mountain this October and was denied.

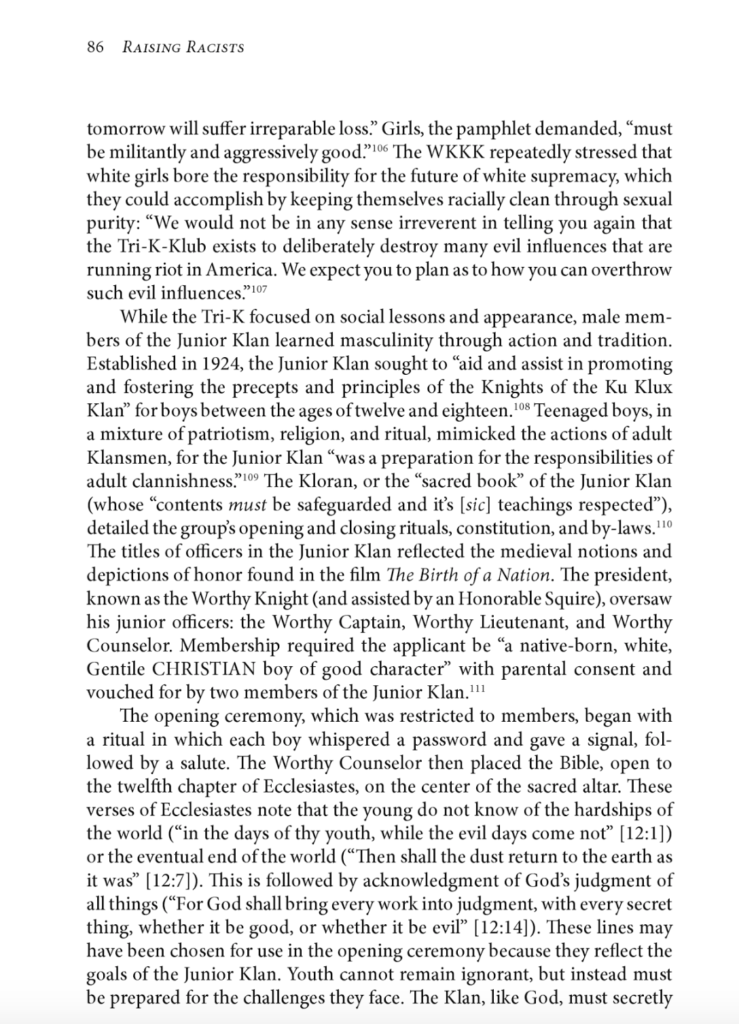

The telling date of "5-6-1923" by itself might prove merely coincidental, far-fetched evidence that the religious message, signed by “H.J. + M.I.P.*” and marked with a carved cross, was the work of Klansmen. However, deeper research into that particular Bible verse, 12:1 from the Book of Ecclesiastes, reveals a potential chilling connection between it and Klan ceremonial rituals. Here is some brief background on the usage of that religious text from the book Raising Racists: The Socialization of White Children in the Jim Crow South by Kristina DuRocher (University Press of Kentucky; March 30, 2011). How disgusting to think that this might've been a spot where the Klan once held notorious cross burnings. Even a simple reference to Atlanta as a “buzzards roost” by a Klansmen in a 1956 article related to rallies at Stone Mountain was loaded enough to give me the shivers.

It is well-known that the hate group bills itself a Christian organization and frequently adheres to the Bible as literal and appropriates and perverts its messages to fit their odious white supremacist ideology. In fact, the group is on the record for even being fond of the verse John 3:16, “For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son that whosoever believeth in Him would not perish but have everlasting life.” Certainly, we may never know if the rock on the walk-up trail carved with the phrase “God So Loved” was the Klan’s handiwork from the days when the group held sway at the mountain or if it is even a reference to John 3:16. Same goes for the carvings of "God Is Love" and "Jesus Saves." Fair enough. And, we do know that the "Jesus Saved The Carpenters" carving is dated 1888, which indicates it was a year after the Venables came to own the mountain and before the official rebirth of the Second Era Klan at Stone Mountain on November 25, 1915. But my gut instinct and the supporting evidence tell me that the startling “Remember Now Thy Creator In The Days of Thy Youth” inscription carved over that wide swath of granite, which is but a stone's throw from the carving of the three Confederate generals, may likely be attributable to them.

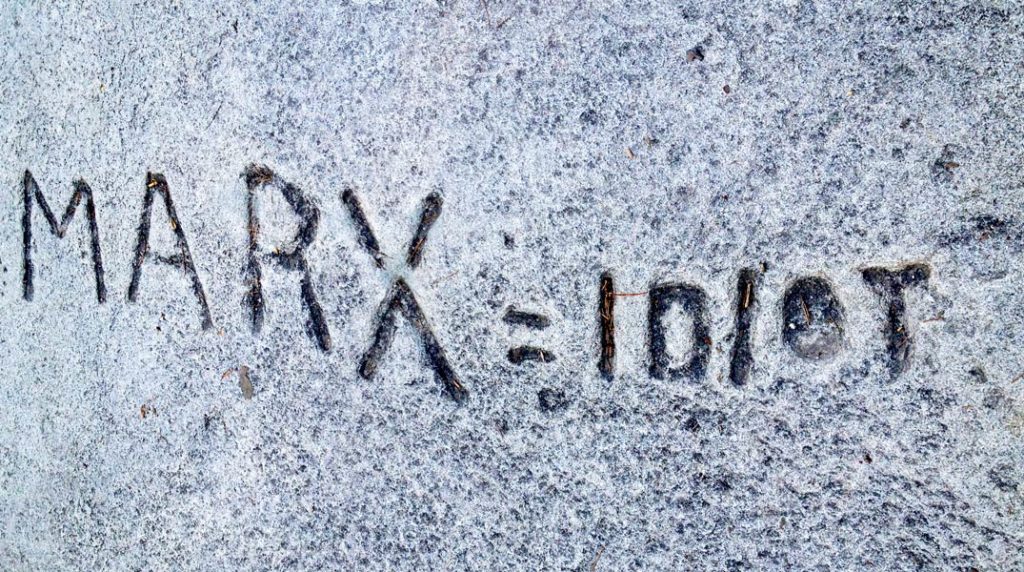

Marx=Idiot I naively used to think this carving referred to philosopher Karl Marx, but the more I've studied the mountain's history, I now shudder to think that this may've actually been a specific insult lodged at Rabbi David Marx of The Temple, which was later bombed by white supremacists on October 12, 1958. Marx led Atlanta's first Jewish congregation for 51 years and was 43 years old when the 20th Century Klan took over Stone Mountain in 1915. Because the mountain has been left largely formally uninterpreted, we may never truly know which Marx. 1958 was of course also the year that the State of Georgia took possession of the mountain.

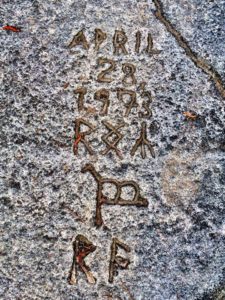

Possible Runic Writing

A handful of carvings on the mountain possibly illustrate runic writing, which the Anti-Defamation League cautions is often used by white supremacists but not in all cases.

I'm also strongly inclined to believe that the Confederate carving itself was largely designed to celebrate the Klan and its white supremacist ideology. Even Helen Plane, of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association (SMCMA) herself suggested that Gutzon Borglum incorporate a tribute to the Klan in his sculpture. “I feel it is due to the Klan which saved us from Negro domination and carpetbag rule, that it be immortalized on Stone Mountain,” she wrote at one point to him. “Why not represent a small group of them in their nightly uniform approaching in the distance?” [Emory University received many of his personal letters, donated by his widow Mrs. Mary Montgomery Borglum, and a has valuable Stone Mountain collection]. While Borglum's original models did not use her idea, his design did include an altar to the Klan, of which he himself became an active member in 1923. Borglum's work was later removed from the mountain by the second carver, Augustus Lukeman, when he left Georgia for South Dakota on the heels of acrimony and scandal.

Just to remind readers, while Helen Plane is often hailed as the original "visionary" of a Stone Mountain monument to the Confederacy, she had followed up on a suggestion that a local attorney named William H. Terrell made in a May 26, 1914 letter to the Atlanta-Constitution, which also provided its own editorial comment championing his idea in the same issue of the newspaper. Governors from the Southern states and community leaders and even past Presidents of the United States of America supported the idea, too. We are often led to believe that the original intention of this and other Confederate monuments was simply to honor the dead who fought for the Confederacy. Even if that may have been the stated intention of some, we know better now that it was about a great deal more for many others, and it's time to understand the overwhelming impact of such monuments as symbols of white supremacy that were erected to basically intimidate oppressed minorities that were free but in no way sharing equal civil and human rights. Intention does not always match impact, and it's now the impact with which our forbears left us to reconcile. So many of these olden statues reflect a white supremacist narrative of those with the means and privilege to write history and to erect such monuments in the wake of a war fought (and lost!) to uphold slavery and secede from the United States of America. So many other people's histories have greatly been excluded and left unmarked in the American narrative — and Stone Mountain's history. Again, I cannot emphasize enough how sad and heart-breaking it is to imagine all of the unknown enslaved people buried across the American landscape without so much as a marker with their names on it. I also consider how many Native American burial grounds we have disturbed over time through settlement and development, and I am proud wherever we have acted to preserve and restore sacred grounds. Inclusivity is definitely long overdue, and it's truly more than okay to proverbially rearrange the furniture and place some of these bygone statues in museums and cemeteries — in their rightful historical contexts. As we embark upon creating new and more diverse monuments, hopefully we can stay true to our best intentions and raise up the best of our humanity. We can honor the past by celebrating a future that acknowledges it has learned from past mistakes.