I chanced upon Bukumba’s grave in Decatur Cemetery for the first time over the summer as I explored the African-American grounds (or lack thereof) of several local historic cemeteries and structures made of Stone Mountain granite, among them Decatur Cemetery, as noted on the historic marker at the cemetery's entrance. I have wondered often about her short life since, and All Souls’ Day seemed an opportune day to share what I’ve so far learned about her.

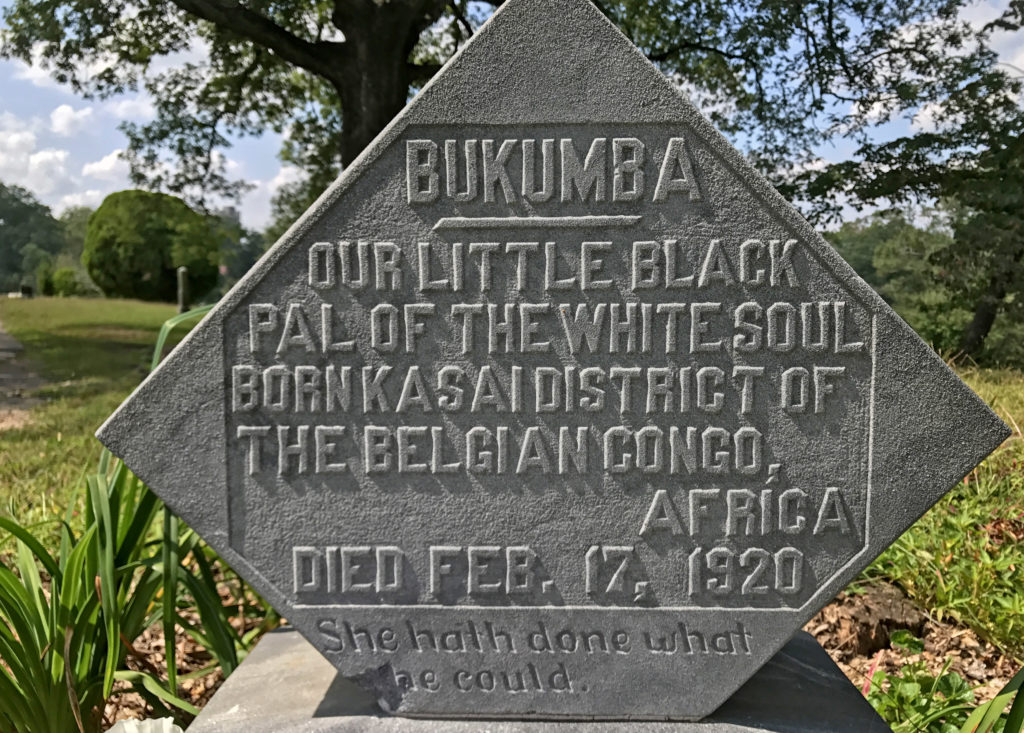

Of course I cringed when I first read her spare gravestone in the “Old Cemetery” section which referred to her as a “our little black pal of the white soul":

BUKUMBA

Our Little Black

Pal of the White Soul

Born Kasai District of

The Belgian Congo,

Africa

Died Feb. 17, 1920

She hath done what

she could.

I dropped her name into Google as I stood there and clicked on a self-guided tour of the cemetery titled “The “Decatur Cemetery: Lives That Made Our City,” which attributes the cringeworthy “pal of the white soul” line to the Bible, as follows:

“Rescued from a difficult life in the Belgian Congo, missionaries brought this young woman to Decatur, where she succumbed to the post-WWI Spanish flu epidemic. The sentiment on her stone, while seemingly insensitive in the 21st century, indicates that she had embraced the Christian religion and her soul was ‘white as snow.’ (Psalm 51)”

No birth date or last name are listed on her grave, but at least two Georgia Death Index entries for her on Ancestry.com put her birth year at 1899 and name her parents as Bamuila Kalawba and Kalaugna Wakamage [sic]. Certainly I was heartened that Bukumba’s final resting place was at least marked, whereas so many African-American’s graves back then, whether enslaved or free, were not and have very often been lost to time. I naturally grew curious about the missionaries that brought her to America from the Belgian Congo and genuinely felt that someone cared enough about Bukumba to mark her grave during a time and place in the South were white supremacy was at its height.

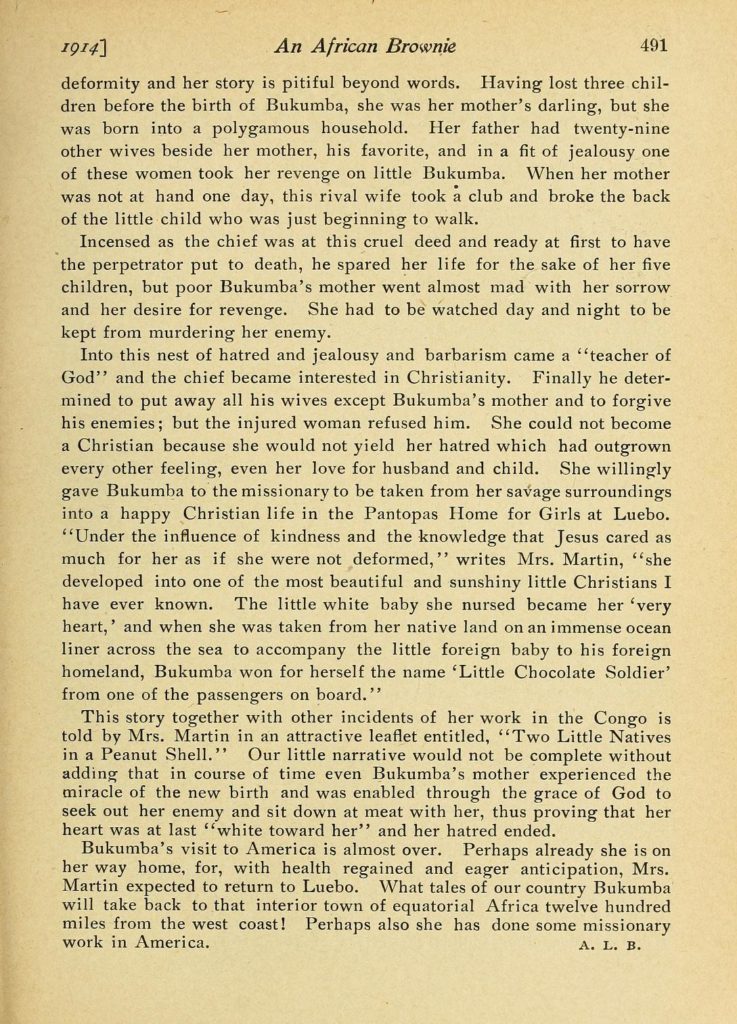

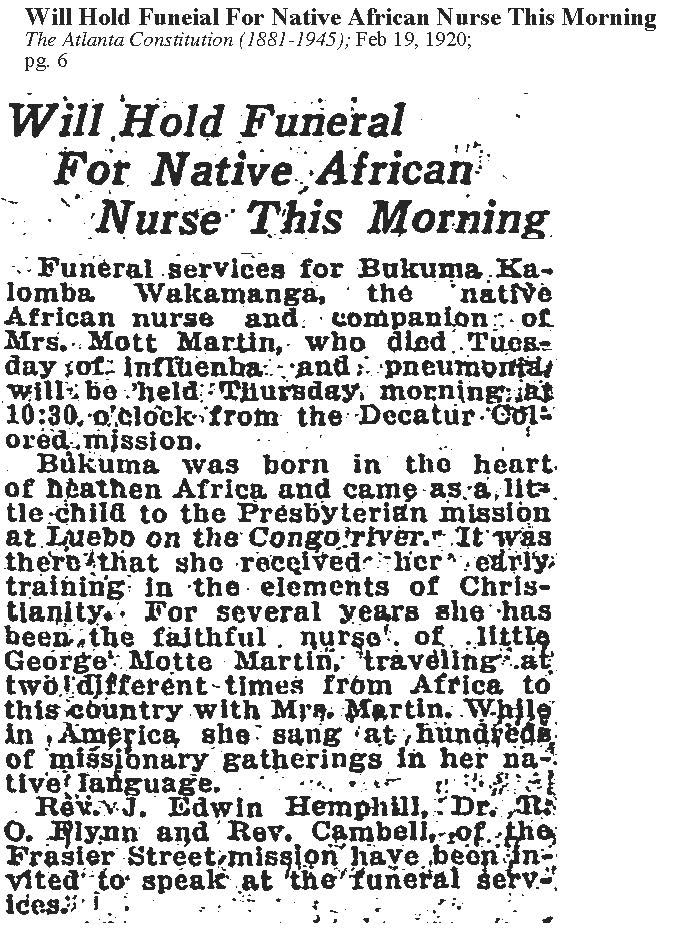

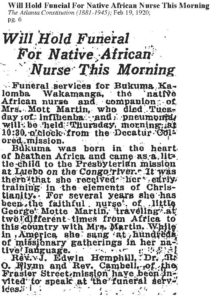

While I’ve not yet located the exact date of Bukumba’s arrival to the U.S., historic newspaper articles and the 1921 “Minutes of Sixty-First General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States” revealed that Presbyterian missionaries, Dr. Motte Martin and his wife Bessie Sentell Martin brought Bukumba to America. Bukumba died in 1920 during a flu outbreak at the age of 21 while caring for others, presumably the Martin’s, as she was referred to in several documents as the companion and nurse of both Ms. Motte Martin and her only child, George Motte Martin. A February 19, 1920 article announcing Bukumba’s funeral did not mention the Martin Family. The Atlanta-Constitution headline read, “Will Hold Funeral for Native Nurse This Morning,” and the brief news item provided her full name as “Bukuma Kalomba Wakamanga” [sic]. However, the aforementioned church minutes describe that Ms. Motte created a "Bukumba Memorial Training School" in Bukumba's honor.

While I’ve not yet located the exact date of Bukumba’s arrival to the U.S., historic newspaper articles and the 1921 “Minutes of Sixty-First General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States” revealed that Presbyterian missionaries, Dr. Motte Martin and his wife Bessie Sentell Martin brought Bukumba to America. Bukumba died in 1920 during a flu outbreak at the age of 21 while caring for others, presumably the Martin’s, as she was referred to in several documents as the companion and nurse of both Ms. Motte Martin and her only child, George Motte Martin. A February 19, 1920 article announcing Bukumba’s funeral did not mention the Martin Family. The Atlanta-Constitution headline read, “Will Hold Funeral for Native Nurse This Morning,” and the brief news item provided her full name as “Bukuma Kalomba Wakamanga” [sic]. However, the aforementioned church minutes describe that Ms. Motte created a "Bukumba Memorial Training School" in Bukumba's honor.

"We are planning to open more classes, clubs, and preaching services in our new Mission (Bukumba School) which was opened September 5th. Eighty-seven pupils came the first Sunday, and we were surprised to find one hundred and sixty present the second Sunday. The number made it impossible to teach, so several classes met outdoors. With some visiting we are confident that hundreds more could be brought in, but we have no room in our crowded building. We have named this new Mission “The Bukumba Memorial Training School” in memory of Mrs. Motte Martin’s faithful African nurse who gave her life for others. This building was made possible by an offer of $800 from the Home Mission Committee, payable when we can raise another $800." (pgs. 117-118)

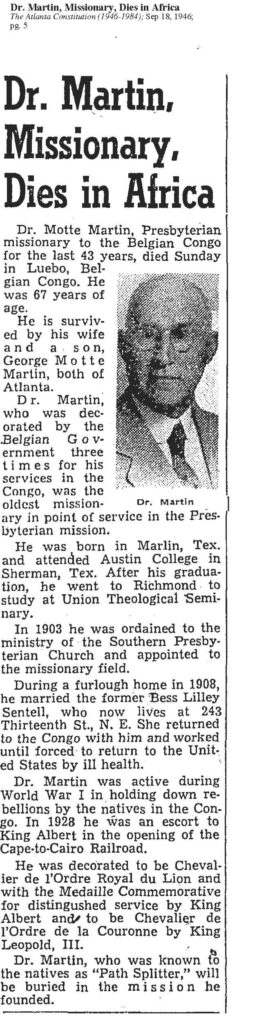

Dr. Motte Martin, a dentist and Presbyterian officiant, lectured frequently at Atlanta’s historic Presbyterian churches and died in 1946 at the age of 67 in Luebo, Belgian Congo, the location of the mission there, and is buried at Oakland Cemetery. Bessie Sentell Coppedge later remarried and passed away in 1967 at the age of 79. She and her son George Martin, who lived to be 96 years old and was 8 years old when Bukumba passed away, are buried in Decatur Cemetery in a different section from Bukumba. None of their obituaries mention Bukumba.

Dr. Motte Martin in The Belgian Congo around 1920. 📸 Presbyterian Historical Society

While Bukumba was imaginably rescued from terrible conditions in the Belgian Congo in the early 1900s, I do wish we knew her thoughts and feelings about being so far from home, how she spent her days here, and about the nature of her ultimately sacrificial service to the Martin Family. Looking into her life has inevitably led me to look into the Presbyterian Church’s overall history, particularly during the schism with Confederate states at the start of the Civil War, and more specifically, Southern Presbyterians and where the Presbyterian Church in Georgia stood historically on the questions of secession and slavery. It has caused me to painfully consider that, however well-intentioned, perhaps on some level Bukumba was a different kind of slave in the name of Christianity. I feel it would be a mistake to simply romanticize her rescue, her religious conversion, and her service. Though it appears Mrs. Motte Martin did in an article about Bukumba called "Africans, There and Here" in the December 1919 issue of Luthern Woman's Work magazine and in a children's book called "Little Whiteface and His Brownie Friends," which sold for 40 cents.

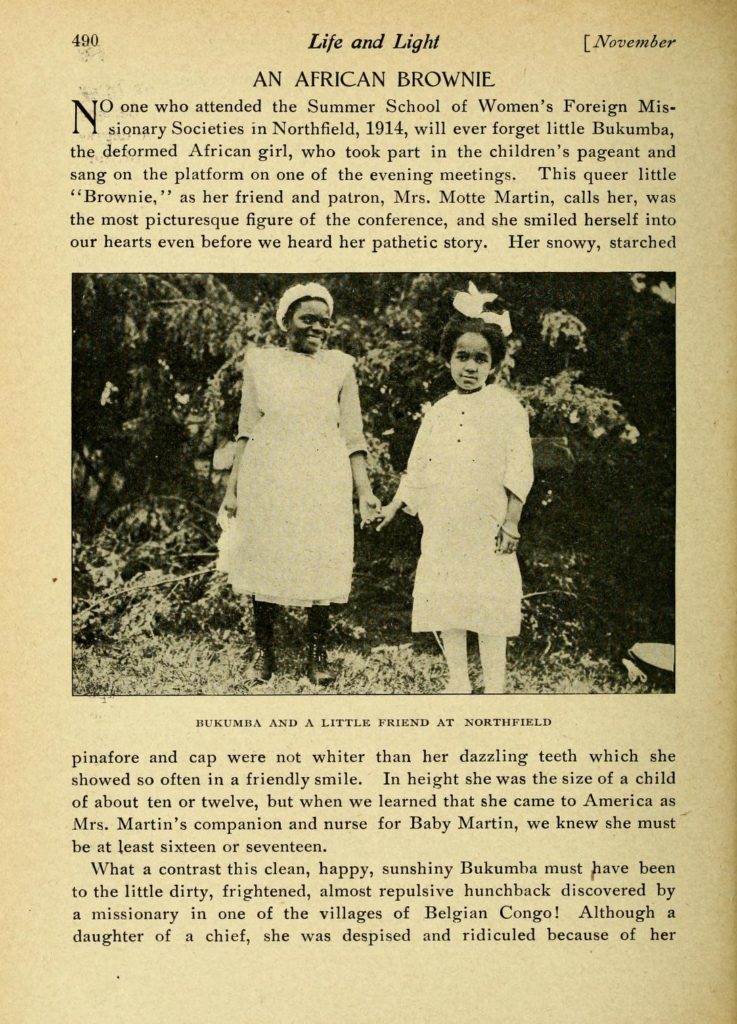

But I have also tried to picture her face (so glad I found some photos!) to hear her singing hymns in her native language, as she's so often mentioned doing in the few articles I found, and to consider the possibility that she may very well have been happy, protected, and supported, even loved, by the Martins. She died so young, in her early womanhood, and it saddens me that her life was not as long and full as those of the missionaries that brought her to this country. Perhaps she is the very sort of person deserving of a monument at the Dekalb County Courthouse or in the town square instead of, for example, little known and rarely (if ever) taught lyric poet and slaveholder Thomas Holly Chivers, also (re)interred in Decatur Cemetery, who seems mostly revered for having been an acquaintance of Edgar Allan Poe.

But I have also tried to picture her face (so glad I found some photos!) to hear her singing hymns in her native language, as she's so often mentioned doing in the few articles I found, and to consider the possibility that she may very well have been happy, protected, and supported, even loved, by the Martins. She died so young, in her early womanhood, and it saddens me that her life was not as long and full as those of the missionaries that brought her to this country. Perhaps she is the very sort of person deserving of a monument at the Dekalb County Courthouse or in the town square instead of, for example, little known and rarely (if ever) taught lyric poet and slaveholder Thomas Holly Chivers, also (re)interred in Decatur Cemetery, who seems mostly revered for having been an acquaintance of Edgar Allan Poe.