Banned Books Week (Sept. 23-29, 2018) is as good a time as any to bring up one of Georgia's and the nation's most praised Southern writers, Flannery O'Connor, whose work has often been challenged and banned by schools, libraries, and even by the Catholic Church. Many may forget that she mentions Stone Mountain in her eponymous story of her 1955 short story collection, A Good Man Is Hard to Find.

“She pointed out interesting details of the scenery: Stone Mountain; the blue granite that in some places came up to both sides of the highway; the brilliant red clay banks slightly streaked with purple; and the various crops that made rows of green lace-work on the ground. The trees were full of silver-white sunlight and the meanest of them sparkled. The children were reading comic magazines and their mother had gone back to sleep.

"Let's go through Georgia fast so we won't have to look at it much," John Wesley said.

"If I were a little boy," said the grandmother, "I wouldn't talk about my native state that way. Tennessee has the mountains and Georgia has the hills.”

I've mentioned here before that I first read this classic short story in my tenth grade English class in Stone Mountain. Awkward teenagers, we of course loved reading about freaks and grotesques in class; plus, this shocking story even mentioned the mountain in our city. It was also important that we were uncomfortable with the use of the "n word" in the story, but I don't think we spent a lot of time discussing it. Decades later I would rediscover O'Connor and read many more of her stories as a more socially conscious adult and realized she actually used the "n word" a lot in her work, but I was also amazed anew that so many of her carefully-crafted vignettes exposed institutionalized racism in the South in the 1950s and early '60s and even skewered "genteel" whites and unloosed the really freaky ones into her tales. To me, the dialogue in many if her stories feel more like an effort to present the crude way Southerners actually talked about black Americans at that time and place in which she was writing. But I also suddenly ran across articles here and there that alleged she may've been a racist based on, in one interpretation, her story "The Displaced Person" and, in another instance, some off-color remarks in letters she had written to a friend a half-cenury ago. A highly educated, devout Irish-Catholic female writer living in the Deep South with a debilitating illness hardly seemed a typical bigot, but anything is possible, I suppose, as even one of her own stories will reveal. However imperfect and human she was, I deep down I don't believe she was a racist and even consider that for a woman writing primarily in 1950's America, her caustic, irreverent writing was a brave offering in its own unique way. I will always be a fan of doing (or writing) something rather than nothing.

"The region is something the writer has to use in order to suggest what transcends it." —Flannery O'Connor

She may not have been "woke" enough by today's standards, but she was at least including race in her work and revealing many supposedly polite Southerners to be anything but "good country people," particularly when it came to racism and the current tensions around integration (see "Everything That Rises Must Converge," written in 1961 and posthumously published in 1965). Just think, the same year that A Good Man is Hard to Find was published in 1955, and O'Connor was making Georgia proud, the Georgia Board of Education was banning textbooks that made the South look bad. I sometimes wonder if they even opened one of her books. Realistically, O'Connor may not have felt empowered to be more outspoken against racial inequality at a time when Klan violence again flared up across the South in opposition to the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement and as her health deteriorated and she grew more dependent on her mother's care while she wrote. The March 19, 1960 edition of the Atlanta-Constitution conveys the political climate of O'Connor's last years. It not only features another proud story about O'Connor, "Look Deeply, Asks Authoress," but to its right is an account of "2 Arrested At Sitdown" about two white youth committing violence at "a Negro college student demonstration in Atlanta eating places" and basically getting away with it. To the left of the O'Connor piece, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is quoted as having just telegraphed President Eisenhower that the segregation protests will continue. In retrospect, we may wish her to have been more heroic or even more of an activist for racial justice beyond merely incisively portraying, even cleverly skewering and satirizing, racist whites on the page. But, if she was, I side with author Marlon James on this one to "embrace the art, not the racist artist" and therefore continue to read and listen to her work (I am a big fan of audiobooks) for new insights into any possible intentions beyond her simply spinning startling and disquieting regional tales. We may never understand her many reasons — personal, spiritual, or professional — as to why "she didn't do more," as some accuse today. But she made very clear that "the truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it."

O'Connor never lived in Stone Mountain, Georgia, but in 1938, she and her family, originally from a line of founding Savannah Catholics, did live briefly in a nice house at 2525 Potomac Ave. in Atlanta's Peachtree Hills East area (said to no longer exist, but there is a home at 2525 Potomac Street today), while her father worked for Dixie Realty and then later for the Federal Housing Authority. My imagination stirs wondering what sights then twelve year-old Mary Flannery O'Connor took in before she and her mom, Regina, moved down to Milledgeville, and her dad, Edward, stayed behind for work (he would pass away but three years later of the same illness said to later claim Flannery's young life at age 39). It would seem next to impossible that she, like most visitors to Atlanta, did not at least see Stone Mountain rising up out of the landscape. I suspect she noticed much more.

It also seems evident to me that, even though O'Connor moved to Milledgeville, she regularly kept up with the Atlanta newspapers and likely even incorporated tidbits of actual news stories, especially crimes, into her often violent tales about evil and redemption. In "A Good Man is Hard to Find" she even refers to reading about escaped convicts from the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary in "the Journal" before the family sets off on their road trip from Georgia to Florida. I found this article about a bank robber that called himself 'The Misfit" and, though "misfit" was a popular term in the 1950s, I wondered if this particular bandit may've inspired O'Connor to name her character after him. Several sensational front-page stories in the 1950s also recounted the penitentiary's first prisoner escapes in over thirty years, which no doubt lent itself to good fiction and was topical. And speaking of banned books, some books are banned in prison.

After recently rereading the short story, "A Later Encounter With the Enemy" (also included in A Good Man Is Hard to Find), I am more convinced than ever that Flannery O'Connor was plain old tired of the never-ending Southern reverence for the Lost Cause and the South's undying fixation on the Civil War. "A Late Encounter With the Enemy," featuring 104 year-old General Tennessee Flintrock Sash, who wasn't even really a general, is a hilarious send-up of the constant pageantry of the Confederacy in its constant, vain effort to appear triumphant. This is the only story of hers that specifically deals with the Civil War, but I sense she wove aspects of its legacy into her oeuvre elsewhere, right down to that lone, probably loaded mention of Stone Mountain in the title story "A Good Man Is Hard to Find" (her middle name, Flannery, is even said to be after a general). She would be surprised to learn that the ghost of General Sash and his ilk are still haunting the South, and Stone Mountain specifically, which will unfortunately see yet more rallies and protests in the months ahead as the debate over Confederate monuments continues. A little over two months after Flannery O'Connor died on August, 3, 1964, the Confederate Flag Terrace at the base of Stone Mountain's walk-up trail was dedicated by the United Daughter of the Confederacy on October, 11, 1964.

After recently rereading the short story, "A Later Encounter With the Enemy" (also included in A Good Man Is Hard to Find), I am more convinced than ever that Flannery O'Connor was plain old tired of the never-ending Southern reverence for the Lost Cause and the South's undying fixation on the Civil War. "A Late Encounter With the Enemy," featuring 104 year-old General Tennessee Flintrock Sash, who wasn't even really a general, is a hilarious send-up of the constant pageantry of the Confederacy in its constant, vain effort to appear triumphant. This is the only story of hers that specifically deals with the Civil War, but I sense she wove aspects of its legacy into her oeuvre elsewhere, right down to that lone, probably loaded mention of Stone Mountain in the title story "A Good Man Is Hard to Find" (her middle name, Flannery, is even said to be after a general). She would be surprised to learn that the ghost of General Sash and his ilk are still haunting the South, and Stone Mountain specifically, which will unfortunately see yet more rallies and protests in the months ahead as the debate over Confederate monuments continues. A little over two months after Flannery O'Connor died on August, 3, 1964, the Confederate Flag Terrace at the base of Stone Mountain's walk-up trail was dedicated by the United Daughter of the Confederacy on October, 11, 1964.

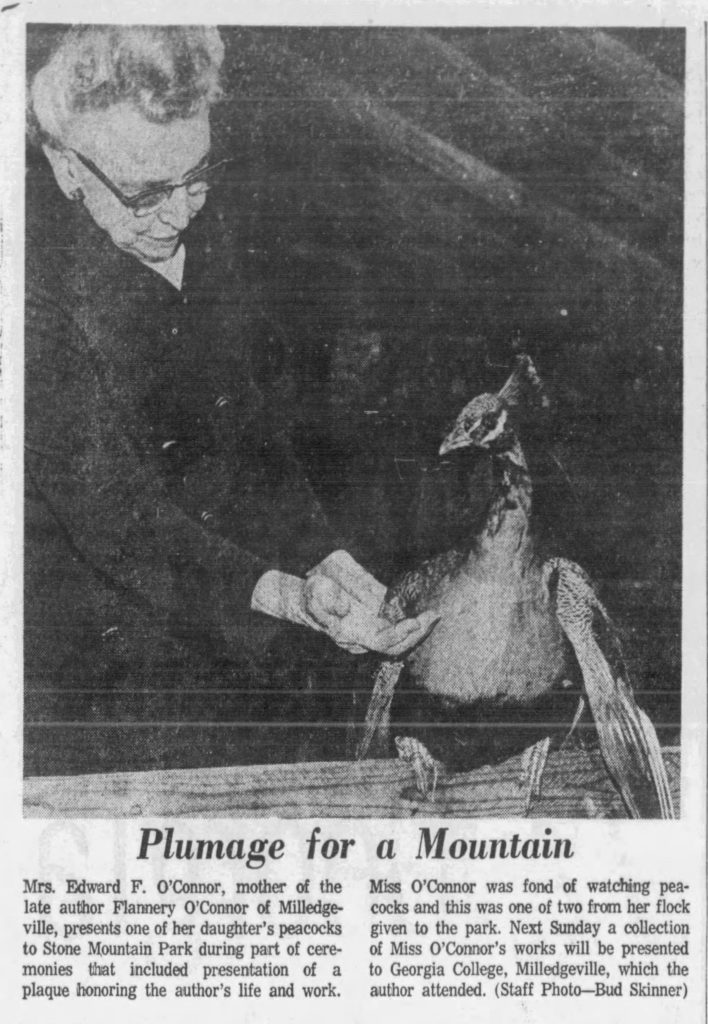

Another lesser known connection between O'Connor and Stone Mountain is that some of her peacocks ended up being donated by her mother (who lived to age 99) to Stone Mountain Park in 1972, eight years after Flannery's death (some also went to the Monastery of the Holy Spirit in Conyers (she was close friends with Trappist monk Thomas Merton, who lived at the monastery in Kentucky) and to Our Lady of Perpetual Help cancer home in Atlanta). I wonder if the decision to donate them to these places was hers or her mother's. Stone Mountain Park had opened in 1965 as a Confederate theme park, and even earlier than that, it also used to maintain the game ranch inside the park in the early 1960s, which later relocated to Lilburn, GA in the early 1980s after a legal battle with the park (note: not a Civil War battle!). Many of the animals there were named in keeping with the Confederate theme, too: Colonel Lee (a blend of namesakes Confederate General Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard and Robert E. Lee), the groundhog that preceded a long line of General Lees, burros named Scarlett, Rhett, and Tara, and a skunk named Sherman. Many thought the Yellow River Game Ranch closed for good in Dec. 2017, but it is slated to reopen in 2019 under new ownership. Andalusia, the home of Flannery O'Conner, in Milledgeville, also reopened this summer under the new management of her alma mater, Georgia College — and, of course, they have peacocks!

In 2010, during the Decatur Book Festival, Stone Mountain Park presented the commemorative plaque made at the time of the donation to Andalusia, which reopened this summer after some renovations under the new management of O'Connor's alma mater, Georgia College: "Flannery O'Connor's Peacocks — These peacocks, from the flock of the late distinguished Georgia writer, were presented to Stone Mountain Park by her mother, Mrs. Edward F. O'Connor, January 8, 1972"