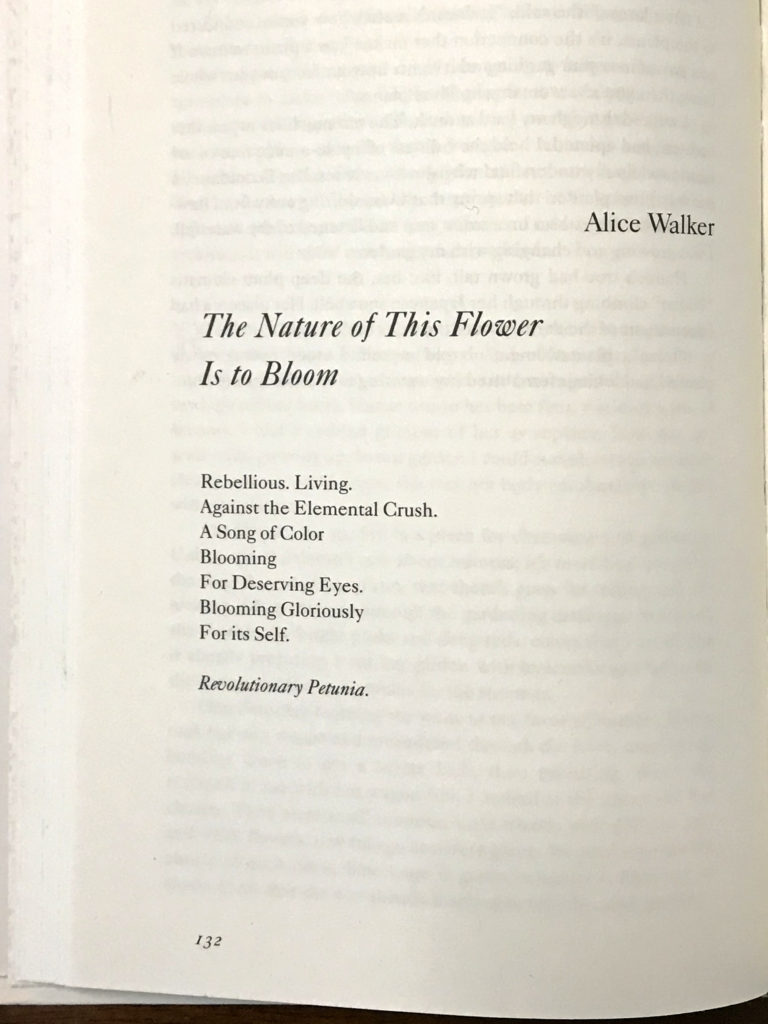

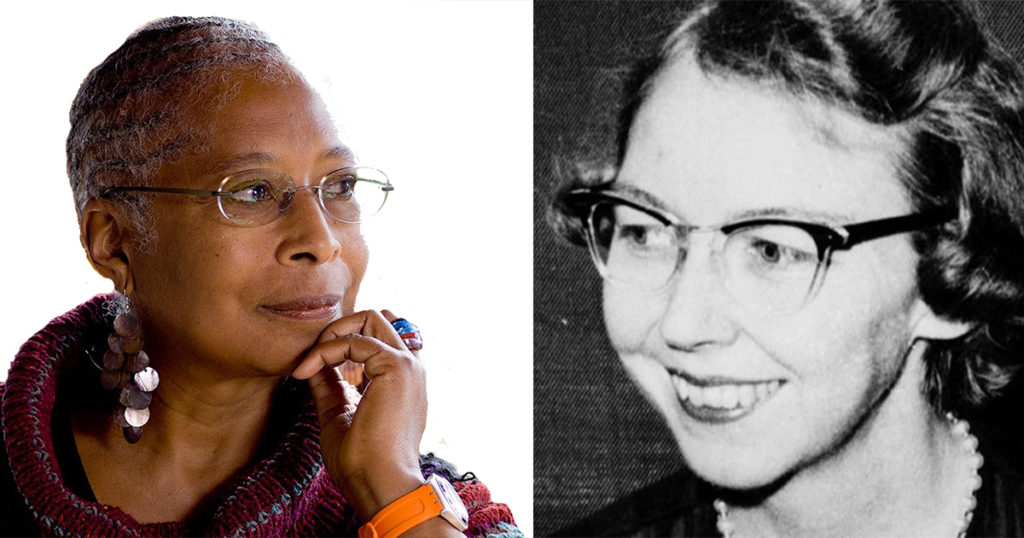

Writers converge upon my mind today, like “tale”winds of March. Today marks the centennial of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s rebirth of wonder. 100 iconoclastic years of marching to his own beat. On February 9th, Alice Walker danced across the threshold of a quarter-century, and a daylong birthday celebration to honor her at 75 will take place in her hometown Eatonton, GA this summer on July 13th (public announcement April 1). And tomorrow, on March 25th, pages everywhere will bend out from their spines in celebratory resurrection of Flannery O’Connor’s wise words and witticisms on her 94th birthday—especially over at her home, Andalusia, in Milledgeville, GA, as well as at her childhood home in Savannah, GA. I’ve written about O’Connor here before, but only since then did I discover an important essay that her Eatonton neighbor, Alice Walker, wrote about her in 1975, the year of my own birth. It’s called “Beyond the Peacock: The Reconstruction of Flannery O’Connor” and is from Walker’s powerful collection In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose. Walker and O'Connor were twenty years apart in age and from different racial and socio-economic backgrounds, but there was a brief time when mere miles separated their respective rural farm homes. So, one day in 1974, Walker, who greatly admired O'Connor but still had some questions, made that half-hour drive over to explore Andalusia and brought her own mother along to share the experience. Here are some excerpts from Walker's essay, but do yourself a favor and read the full 20-page piece of "womanist prose" linked above:

Writers converge upon my mind today, like “tale”winds of March. Today marks the centennial of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s rebirth of wonder. 100 iconoclastic years of marching to his own beat. On February 9th, Alice Walker danced across the threshold of a quarter-century, and a daylong birthday celebration to honor her at 75 will take place in her hometown Eatonton, GA this summer on July 13th (public announcement April 1). And tomorrow, on March 25th, pages everywhere will bend out from their spines in celebratory resurrection of Flannery O’Connor’s wise words and witticisms on her 94th birthday—especially over at her home, Andalusia, in Milledgeville, GA, as well as at her childhood home in Savannah, GA. I’ve written about O’Connor here before, but only since then did I discover an important essay that her Eatonton neighbor, Alice Walker, wrote about her in 1975, the year of my own birth. It’s called “Beyond the Peacock: The Reconstruction of Flannery O’Connor” and is from Walker’s powerful collection In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose. Walker and O'Connor were twenty years apart in age and from different racial and socio-economic backgrounds, but there was a brief time when mere miles separated their respective rural farm homes. So, one day in 1974, Walker, who greatly admired O'Connor but still had some questions, made that half-hour drive over to explore Andalusia and brought her own mother along to share the experience. Here are some excerpts from Walker's essay, but do yourself a favor and read the full 20-page piece of "womanist prose" linked above:

“I remind myself of her courage and how much—in her art—she has helped me to see. She destroyed the last vestiges of sentimentality in white Southern writing; she caused white women to look ridiculous on pedestals, and she approached her black characters—as a mature artist—with unusual humility and restraint. She also cast spells and worked magic with the written word. The magic, the wit, and the mystery of Flannery O’Connor I know I will always love, I also know the meaning of the expression “Take what you can use and let the rest rot.” If ever there was an expression designed to protect the health of the spirit, this is it.”

♦♦♦

“Whether one ‘understands’ her stories or not, one knows her characters are new and wondrous creations in the world and that not one of her stories—not even the earliest ones in which her consciousness of racial matters had not evolved sufficiently to be interesting or to differ much from the insulting stereotyping that preceded it—could have been written by anyone else. As one can tell a Bearden from a Keene or a Picasso from a Hallmark card, one can tell an O’Connor story from any story laid next to it. Her Catholicism did not in any way limit (by defining it) her art. After her great stories of sin, damnation, prophecy, and revelation, the stories one reads casually in the average magazine seem to be about love and roast beef.”

♦♦♦

“There is a garish new Holiday Inn directly across Highway 441 from Flannery O’Connor’s house, and, before going up to the house, my mother and I decide to have something to eat there. Twelve years ago I could not have bought lunch for us at such a place in Georgia, and I feel a weary delight as I help my mother off with her sweater and hold out a chair by the window for her. The white people eating lunch all around us—staring though trying hard not to—form a burred backdrop against which my mother’s face is especially sharp. *This* is the proper perspective, I think, biting into a corn muffin, no doubt about it.

As we sip iced tea we discuss O’Connor, integration, the inferiority of the corn muffins we are nibbling, and the care and raising of peacocks.

‘Those things will sure eat up your flowers,’ my mother says, explaining why she never raised any.

‘Yes,’ I say, ‘but they’re a lot prettier than they’d be if somebody human had made them, which is why this lady liked them.’ This idea has only just occurred to me, but having said it, I believe it is true. I sit wondering why I called Flannery O’Connor a lady. It is a word I rarely use and usually by mistake, since the whole notion of ladyhood is repugnant to me. I can imagine O’Connor at a Southern social affair, looking very polite and being very bored, making mental notes of the absurdities of the evening. Being white she would automatically have been eligible for ladyhood, but I cannot believe she would ever really have joined.”

♦♦♦

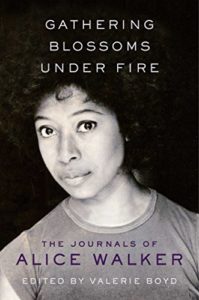

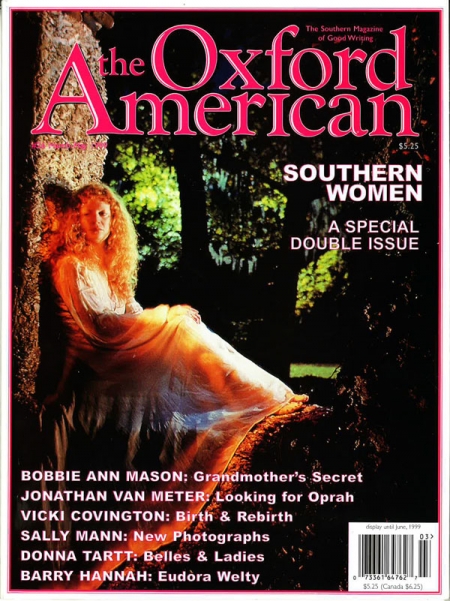

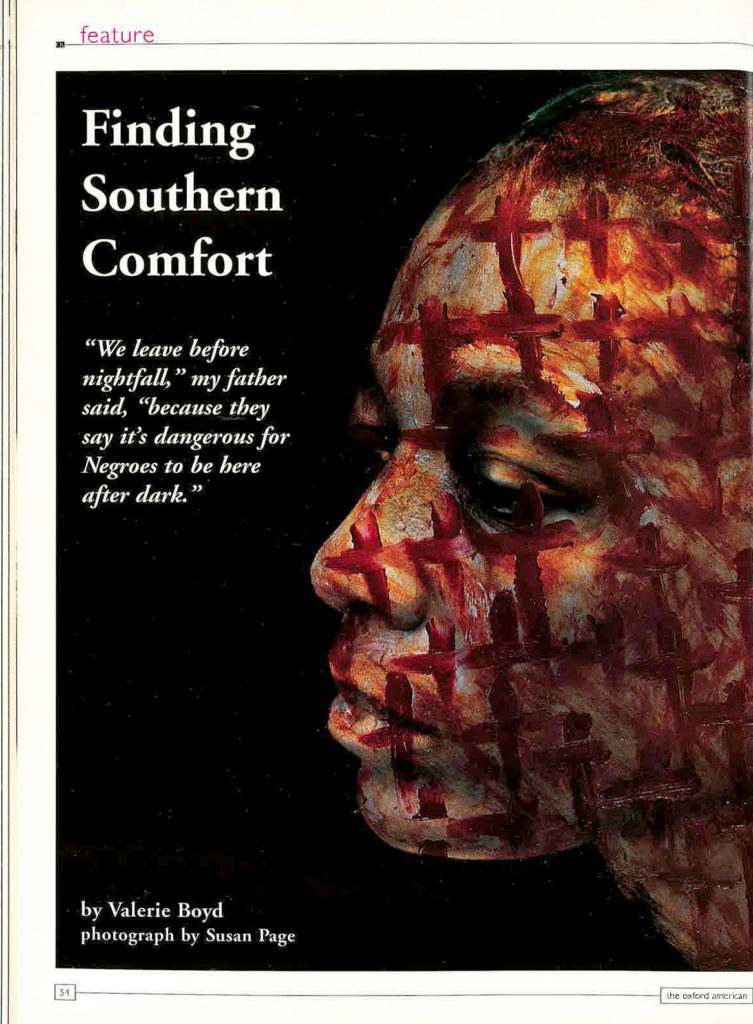

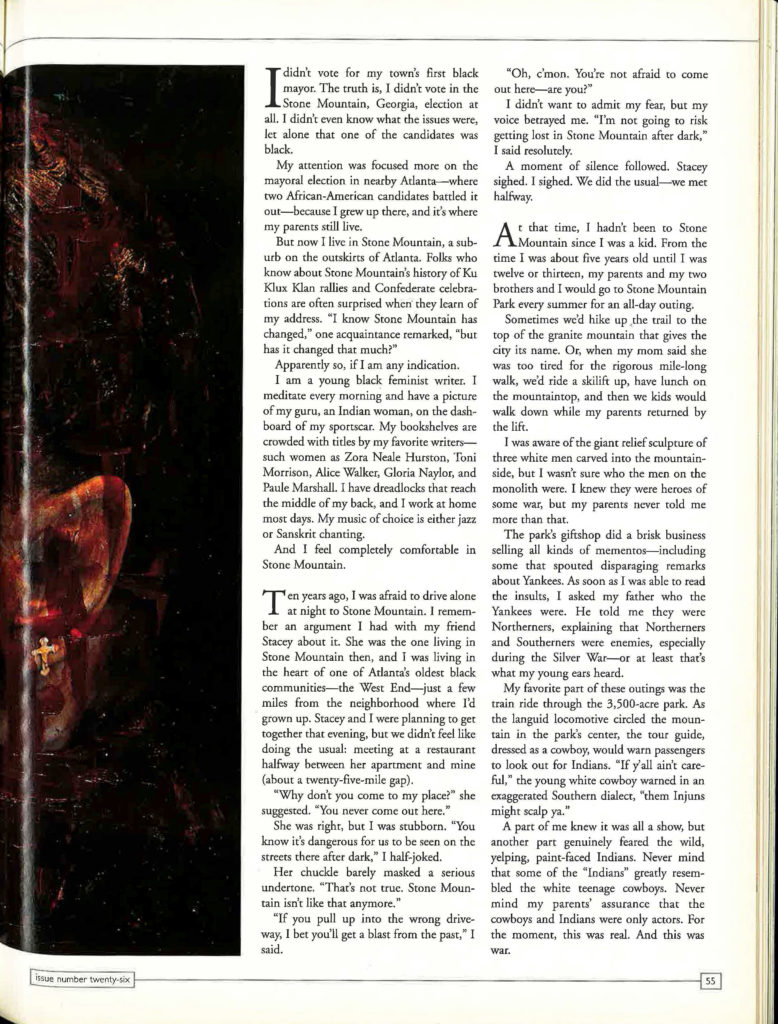

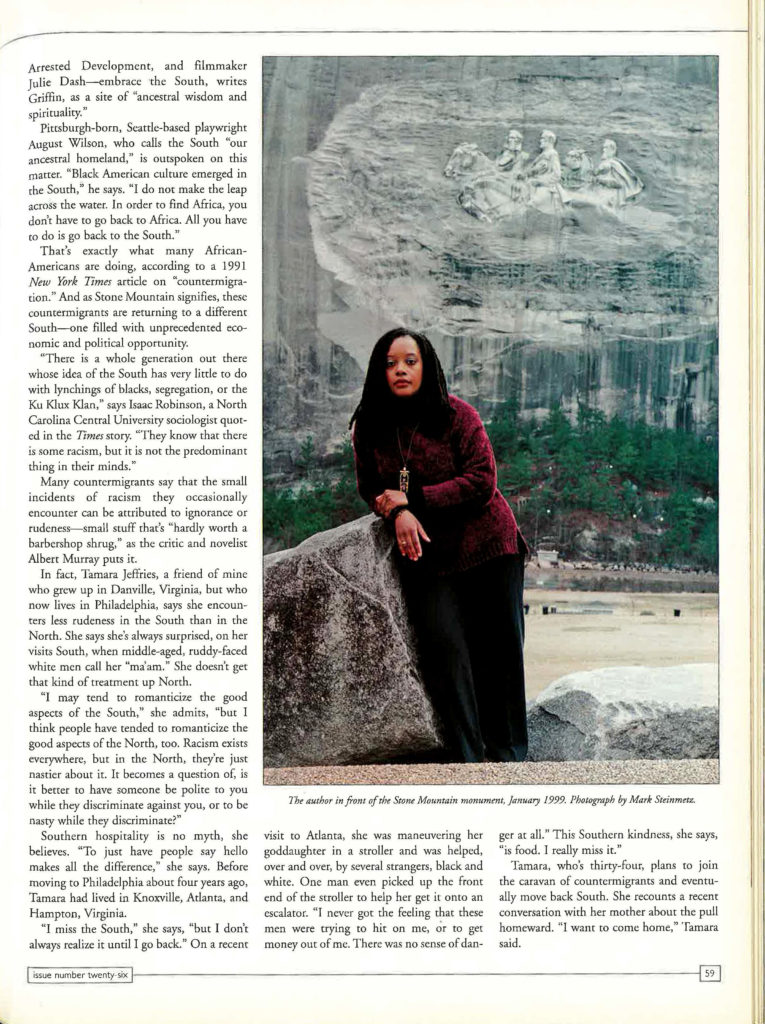

And while doing this bit of literary birthday groundskeeping with Flannery O'Connor and Alice Walker, I also unearthed another surprise — an essay in the Oxford American about my hometown, from 1999, called "Finding Southern Comfort," by acclaimed author and UGA professor Valerie Boyd about the first major shift in Stone Mountain's demographic and cultural landscape just over twenty years ago, not long after I graduated from Stone Mountain High. Boyd was living in Stone Mountain at the time she wrote the piece, and I was months away from college graduation when "Finding Southern Comfort" was published. Reading it now for the first time, after spending recent years "mining" this landscape here on the website, truly felt like coming home, especially in the sense that, even twenty years apart, the article shares my hopeful vision of a place capable of transcending its past — but not without examining that past with historic integrity. Talk about coming full circle, Boyd is now my neighbor! "Finding Southern Comfort" belongs here, if anything about Stone Mountain does, and I'm grateful to Boyd for permission to share it (and since I posted this, she wrote a follow-up piece for Oxford American in August 2020, too). She is co-chairing the upcoming 75th birthday celebration for Alice Walker in July with Lou Benjamin in Eatonton and is handling the literary programming for it. Boyd will publish Gathering Blossoms Under Fire: The Journals of Alice Walker with Simon & Schuster in April 2022.

"Finding Southern Comfort" | OXFORD AMERICAN | ISSUE 26, SPRING 1999

"The Willson Center’s Global Georgia Initiative presents global problems in local context with a focus on how the arts and humanities can intervene. The series is made possible by the support of private individuals and the Willson Center Board of Friends."