152 Nassau Street, Google Streetview

Okeh, okay, unpopular opinion alert. I love old buildings. Ones with unique back stories even more. I generally don’t patronize chain restaurants and am not a proponent of transforming cities into Anytown, USA. You know I dig historic preservation. But some words about the campaign to save 152 Nassau Street, NW in Atlanta from demolition and from becoming a 21-story Margaritaville Vacation Club hotel. This whole thing fails to emphasize enough, if at all, the outsized role that musician Fiddlin’ John Carson played in Georgia’s racist politics for decades and risks further glorifying him in the name of music history, when his full-fledged place in Georgia history is more notorious and complicated. It's actually breathtaking how he epitomizes white supremacy in so many ways.

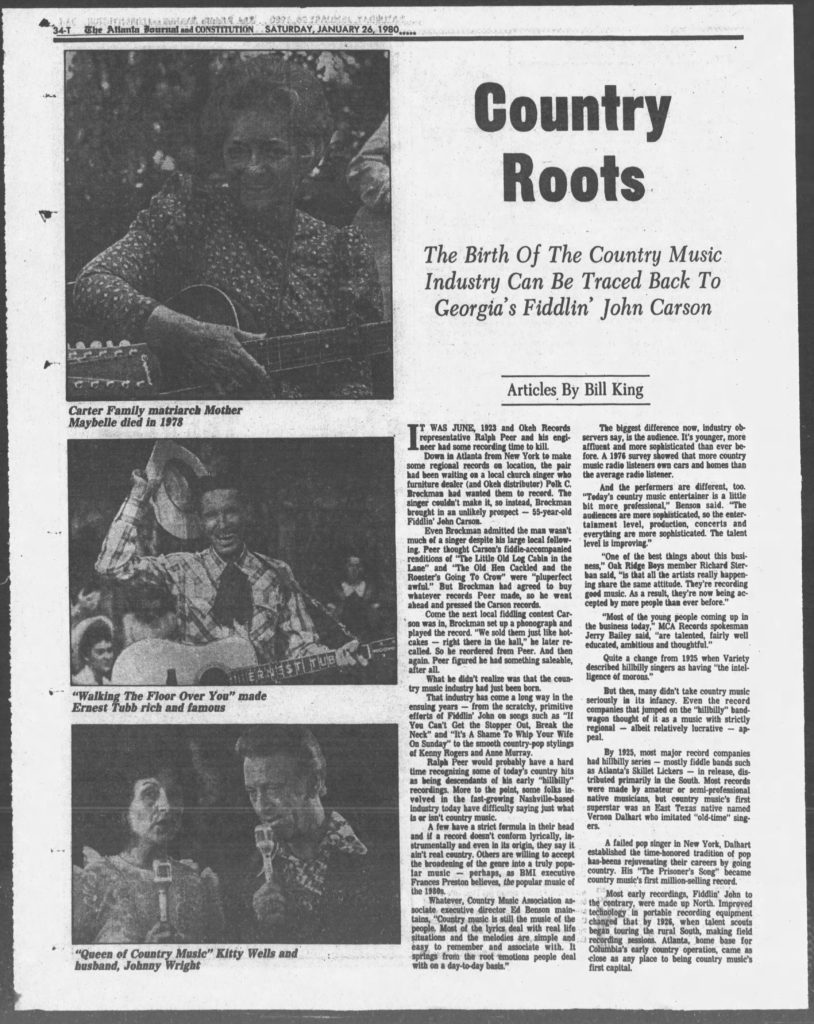

Efforts to save 152 Nassau Street seem primarily pinned to Fiddlin’ John Carson’s having recorded the first purported country hit record for Okeh Records during a pop-up session in that building, on June 14, 1923, before country was called country. The building was regularly rented out by a variety of companies (see gallery below), and its life as a recording studio appears to have been brief. Thankfully, the petition to save the building also acknowledges that African-American blues musicians—such as Lucille Bogan, Fannie Mae Goolsby, Eddie Heywood, and the Morehouse College Quartet, and later, R&B artist Major Lance—are said to have recorded sessions in this building, but the press coverage mostly, then and now, latches onto Fiddlin’ John Carson, probably because he's much more well-known. I'm curious what documentation exists linking the other musicians to the building. Atlanta’s music history is certainly a “multicultural mishmash,” to borrow a phrase from David Hadju’s recent piece in The Nation from June.

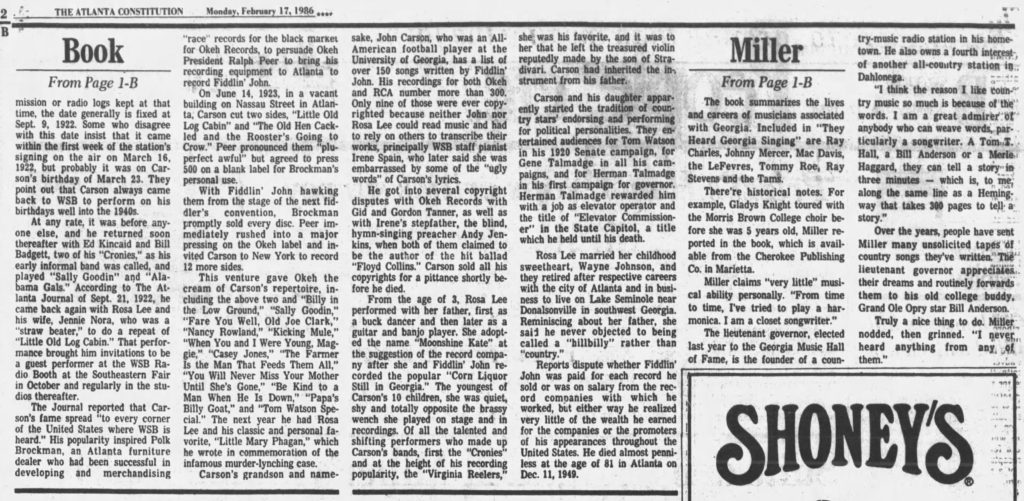

What’s NOT getting mentioned is that Fiddlin’ John Carson was a regular fixture at racist Dixiecrat Eugene Talmadge’s campaign rallies beginning in 1932 (a Dixiecrat before they were officially called that). He was so deep inside pro-Nazi Gene Talmadge’s pocket that he later ended up on the governor's payroll in 1941, as an elevator man at the capitol and would often open the house sessions with his fiddling. Herman Talmadge kept him on as “elevator commissioner,” starting in 1947, during the “three governors controversy” (which I posted about recently) until Carson’s death in December 1949 at age 81. Beyond the Talmadge dynasty, he’d also later perform at gubernatorial campaigns for Ed Rivers and Marvin Griffin.

What’s NOT getting mentioned is that Fiddlin’ John Carson was a regular fixture at racist Dixiecrat Eugene Talmadge’s campaign rallies beginning in 1932 (a Dixiecrat before they were officially called that). He was so deep inside pro-Nazi Gene Talmadge’s pocket that he later ended up on the governor's payroll in 1941, as an elevator man at the capitol and would often open the house sessions with his fiddling. Herman Talmadge kept him on as “elevator commissioner,” starting in 1947, during the “three governors controversy” (which I posted about recently) until Carson’s death in December 1949 at age 81. Beyond the Talmadge dynasty, he’d also later perform at gubernatorial campaigns for Ed Rivers and Marvin Griffin.

And, even long before then, in 1915, Carson wrote “Little Mary Phagan” in response to Governor John Slaton’s commutation of Leo Frank’s death sentence to life imprisonment, which fomented public outrage and anti-Semitism and many believe contributed to Leo Frank’s kidnapping and murder on August 17, 1915, where Carson entertained crowds while Leo Frank's body hung from an oak tree in Marietta. 106 years later the Leo Frank case has been reopened by Atlanta's new Conviction Integrity Unit. Even Carson's daughter, who performed with him for years as “Moonshine Kate,” stated that her dad followed the lynch mob that day and how it inspired him to pen a follow-up ballad, “The Grave of Mary Phagan."

In my opinion, more than Okeh Records, it seems Carson's relationship as a regular on WSB radio, beginning in 1922, positioned him as recording star. One must keep in mind that 1923 was a peak year for white supremacy in Atlanta and the year the Confederate carving on Stone Mountain officially began with Gutzon Borglum at the helm (this is why merchandise at Stone Mountain Park uses the year 1923). And, even a few months before Leo Frank was lynched, and for years to come, Carson was regularly champion at the national fiddlers' conventions held annually in Atlanta, which benefited the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

All to say (and there's likely even more where this came from), save the building if it's indeed warranted, but please be mindful of the bigger narrative beyond music arcana here. Even if the city preserves 152 Nassau Street, because it may've been the first recording studio in the South, the unavoidable fact of the matter is that Fiddlin' John Carson may well be the devil that went down to Georgia in the eyes of many. He was immortalized, after all, by Charlie Daniels in the song, “The Devil Went Down to Georgia.” But if they demolish the building, they’ll say “hell broke loose in Georgia," (another reference to a traditional song Carson recorded), and we'll be "wastin' away in Margaritaville."

And by 1986, then Lt. Governor Zell Miller brought Fiddlin' John Carson back into popular discourse with a book about country music history called, They Heard Georgia Singing. Years later he would go on to become Georgia's Governor as a Democrat and then ignominiously (to me) switch parties in years to follow.

Tabloid Scrutiny

The newspapers covered Carson and his many children regularly. He and his sons were often jailed. One son, Grady, was publicly accused of beating his wife and was later killed in a bar fight. A daughter was killed in a car accident, and another daughter accidentally drank Lysol but survived (it's entirely possible, given the times, that she thought it was moonshine?).

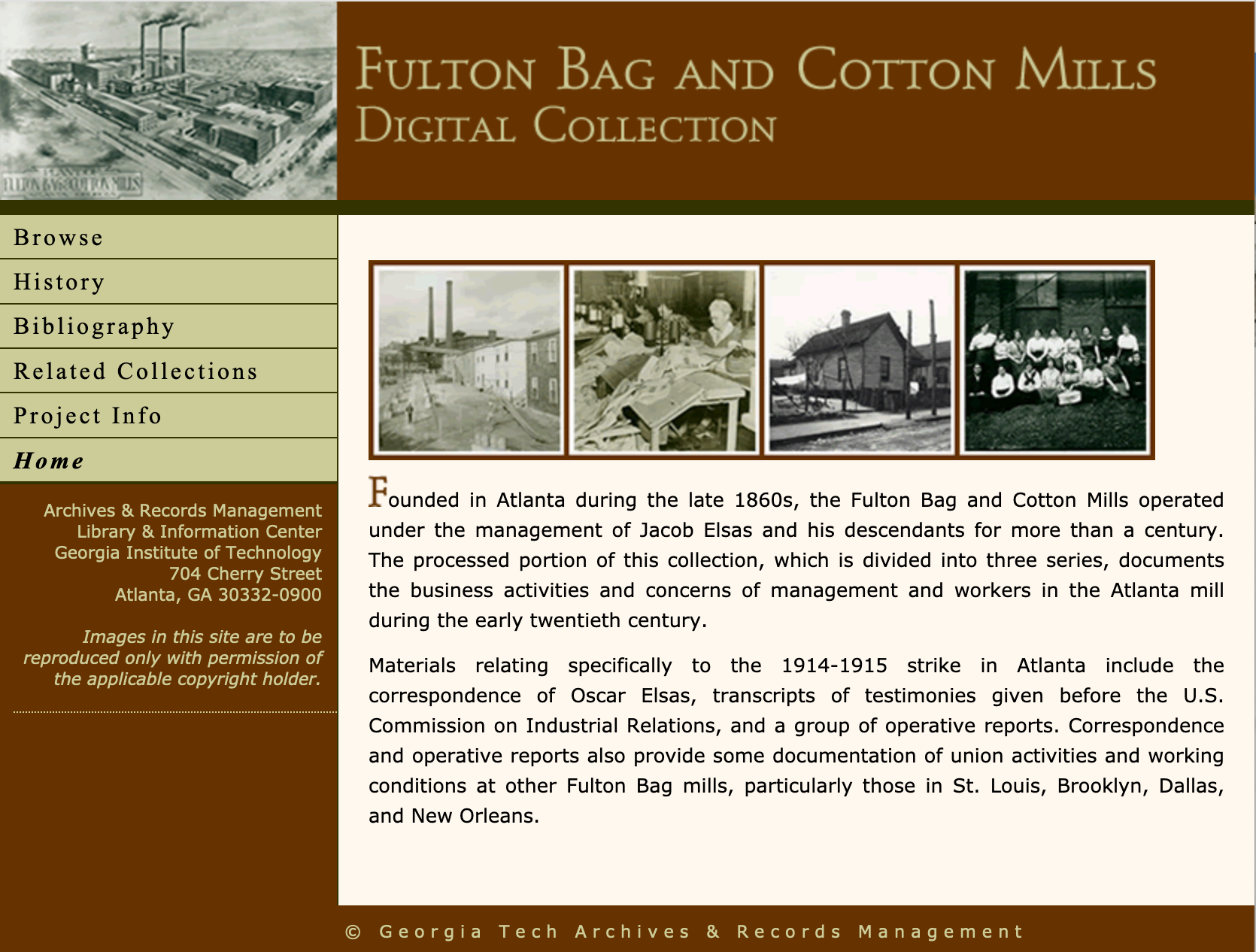

Cabbagetown

Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills, where Fiddlin' John Carson and many members of his family were employed, as they lived in Cabbagetown. "Fulton Bag strike coincided with an outbreak of mass hysteria in Georgia surrounding the trial, conviction and lynching of Leo Frank (at which Carson fiddled), a Jewish pencil factory manager, for allegedly murdering a teenaged employee, Mary Phagan. Cabbagetown was a center of anti-Frank sentiment, and some of that animus was transferred to members of the Elsas family because they too were Jewish and, perhaps, because workers connected the labor practices of Fulton Bag with the system of industrial efficiency which Frank had been installing at the pencil factory."