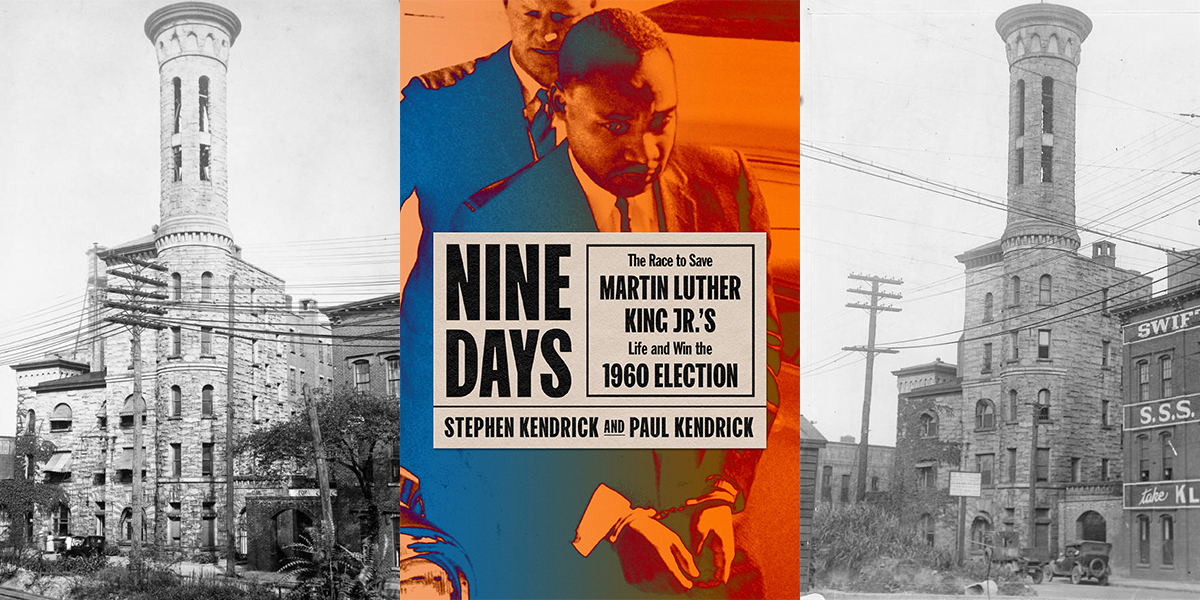

You don't know how much I appreciated, after scrolling through a sea of familiar, repeating King quotes and videos on social media on MLK Day, seeing a link to an excerpt from Nine Days: The Race to Save Martin Luther King Jr.'s Life and Win the 1960 Election. I felt like I hit upon "a stone of hope" in my newsfeed. What a powerful reminder, of a lesser known, but hardly insignificant "letter from jail" written by Martin Luther King, Jr. over nine days in late October 1960 when he was first incarcerated for a few days in Atlanta's Fulton Tower before being transferred to the Dekalb County Jail and then onto Reidsville Prison. We often hear about King's hugely important "Letter From a Birmingham Jail," but what a major chapter in Atlanta history and Civil Rights history is this!

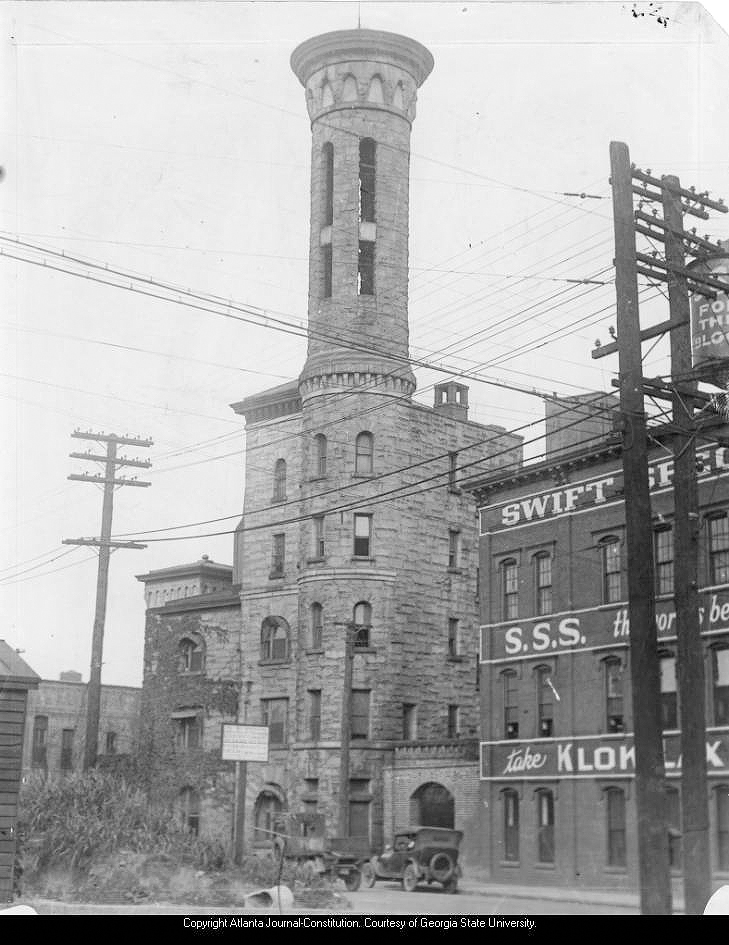

"Fulton Tower with the State Capitol in the background during demolition, 1962"

I've included mention before of the bygone Fulton Tower among the numerous buildings in and around Metro Atlanta, and beyond, constructed of Stone Mountain granite, so it's no surprise this behemoth jail, which rose above the State Capitol, was dubbed "Big Rock." The building, located in downtown Atlanta on Butler Street at the time, was completed in 1898 and built by the very county prisoners incarcerated there, and the idea then was that the structure would not appear at all as a prison but rather resemble "a modern residence" (perhaps such as historic Rhodes Hall, also made of Stone Mountain granite — the Georgia Archives were long housed here, today The Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation is headquartered there, and it's worth noting that in 1904 the residence was originally called Le Rêve, which means "the dream" in French, if only because for the poetic ring it has to me while bringing it up in a post about Dr. King, whose "I Have A Dream" speech turns 60 this August). Fulton Tower was demolished in 1962 after being abandoned by the city, coincidentally not long after Dr. King was briefly jailed there. So, of course, one of the pull quotes Literary Hub singled out from the book excerpt caught my eye: "The city jail known as Big Rock: it was a 19th-century Stone Mountain granite structure with a tall, narrow tower extending a hundred feet into the air." What an image! The same civil rights leader that would but a few years later call for freedom to ring "from every mountainside" locked inside a prison constructed of one of those very mountains.

King had been arrested for participating in a sit-in at Rich's Department Store along with dozens of other activists that were also arrested that week at other nearby sit-ins for "trespassing" and "disorderly conduct," but In a matter of days, he had suddenly become national news and the "October surprise" ahead of the 44th presidential election between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Many of the other protesters that had been arrested with Dr. King joined him in his cell block at Fulton Tower, but most of the others, including King's brother Rev. A.D. King, were sentenced to labor at the notorious Atlanta Prison Farm and/or released shortly thereafter, while Martin Luther King, Jr. remained jailed in three locations as mentioned above (Fulton Tower, Dekalb County Jail, and then Reidsville Prison).

What I hadn't expected while devouring Paul Kendrick's and Stephen Kendrick's important and exhaustively researched book, which was published a year ago this month, were significant mentions of the old Atlanta Prison Farm. Somehow I missed this important book in my deep dive into the prison farm back in September, but that the book was published only six days after the Capitol insurrection and the inauguration of President Biden explains in part where my mind may've been at the time. Interestingly enough, just yesterday on the heels of MLK Day, bulldozers arrived to presumably begin clearcutting trees in the South River Forest at the old prison farm to make way for a multi-million dollar public safety compound, so the site is still very much on my mind and in the news. I was indeed already aware that many sit-in demonstrators had been sent there during the Civil Rights Movement, including King's brother, Rev. A.D. King, and had even included articles about A.D.'s and others' arrests in March 1960 and their significance to the space's century-long history. I had also included, without yet connecting the dots to Dr. King and his brother (and surely many more connections I'll be exploring!), a Spelman Spotlight article from May 1, 1977, about students participating in the Martin Luther King Jr. Internship Program at the prison farm through the years. But somehow I hadn't yet truly zeroed in on those nine days October 1960 until seeing the book excerpt (!), and the following quotes from the book about some of the harrowing conditions at the prison farm during then certainly could've added even more credibility to the situation I was trying to describe last year, decade by decade (but better late than never!):

“Donald Hollowell raced to Judge Webb’s courtroom for the second time in as many days despite being busy representing two Black students, Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes, whom the University of Georgia was refusing to enroll. Twenty-five more Black protesters ended up in jail that day (as well as a white counter-protester), with three taken to join Lonnie and company under the same Georgia trespassing law, and the other twenty-two being sent to the city’s prison farm—where they would have to labor in the same Georgia trespassing law, and the other twenty-two being sent to the city’s prison farm—where they would have to labor in the fields—for disorderly conduct under the city’s statute. These students would be staying in what one described as “modern slave quarters.” There was no natural light, only a few fluorescent bulbs, so it felt as if they were being housed deep underground. A pungent combination of urine, vomit, and perspiration overwhelmed the smell of disinfectant. The bench was showing little indulgence toward the students being sent there...”

“More than half of the students waking up that Thursday morning in Atlanta’s jails were women. Having heard stories of white guards raping Black female prisoners, Herschelle Sullivan and other leaders set up a rotation in advance so at least one student was always keeping watch during the night. Over at the Atlanta Prison Farm, the student Norma June Wilson listened as a white male guard set his gun down and raped a woman prisoner who was in the bunk bed under her. What Atlanta women protesters endured is part of the story of sexual violence suffered by Black women at the hands of white men throughout the civil rights movement. In this terror, guards asserted power without accountability over women protesters who were left physically vulnerable. Before Rosa Parks resisted arrest on the Montgomery bus, she was a trained activist who investigated the systematic rape of area Black women for the NAACP.”

📷 "View of the old Fulton County Jail, know as Fulton Tower, Atlanta, Georgia, 1930s?" / AJCP338-037d, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Not in the book, but something else that didn't click until today when looking deeper at key newspaper articles about those nine days in 1960: among the officers that had arrested dozens protestors at sit-ins during the days surrounding Martin Luther King, Jr.'s arrest at Rich's was none other than Detective J.D. Hudson, who would later oversee the Atlanta Prison Farm during its final decades. The Atlanta-Constitution article from October 21, 1960 seems to go out of its way to include, perhaps for optics, that a Black officer was among those arresting Black people that were protesting in favor of integration: “A Negro detective, J.D. Hudson, assisted three white officers in making 25 arrests at the Union News lunch room in Terminal Station…Hudson said he asked the Rev. A.D. King and each of the others present individually to move on and when they refused brought charges. Cross-examined by Attorney D. L. Hollowell, Hudson said each of the 22 persons told him they were attempting to be served food.” I can't imagine that was an easy position for Hudson to be in, especially since he was not himself afforded the equal dignity of being served food in a public establishment at that time. It's hard to believe things were ever like this and therefore ever so important we remember. More about J.D. Hudson here.

[Editor's Note, 4/16/23: Earlier this year I found an article from the 1964 issue of The Atlantic called "Four and A Half Days in Atlanta's Jails" by Gloria Wade Bishop (known today as Dr. Gloria Wade Gayles of Spelman), that not only echoes Dr. King's "Letter From a Birmingham Jail, which turns 60 today, but also shed light on why, at least in her case, the police officers that arrested her and others protesting segregation were also Black officers: “Negro police arrested and booked us because the city accepted an editorial suggestion in the Atlanta Constitution. The editorial advised that Negro police be used to handle civil rights demonstrators, apparently because the editors believed chances of police brutality would be lessened if Negroes handled Negroes and white sympathizers.” Maybe this was the same sentiment during those nine days in 1960, as well.