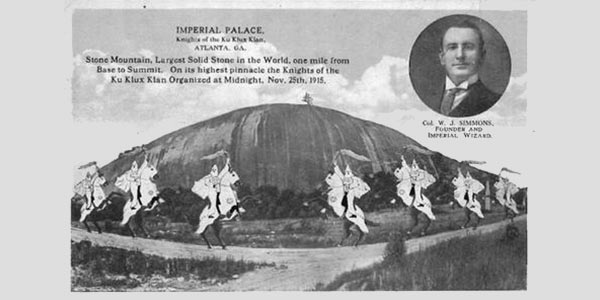

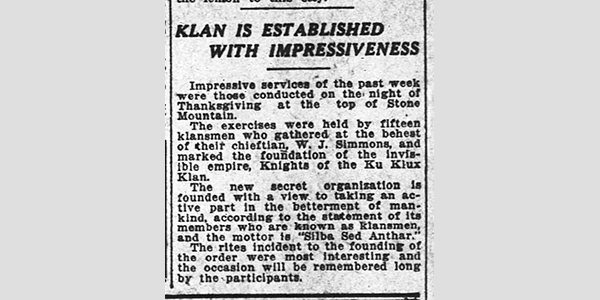

It’s 2015, and not one—but four!—Confederate flags still fly at the base of Stone Mountain, once an official bastion of white supremacy, when the Second Era KKK declared it its 20th Century rebirth place 100 years ago this November. The State of Georgia bought the property from the Venable Family in 1958, and even condemned the land in order to nullify an easement that would’ve still allowed the hate group to hold meetings at the mountain. And yet, today thousands of people of every race, religion, culture, and creed from across the world climb Stone Mountain and visit Stone Mountain Park yearly, which is great cause for celebration. And it’s high time Georgia's government and the park's administrators publicly reconcile the park's past ties (and obviously still lingering) with a hate group and lower these flags for good. It’s time to admit that the flags are a slap in the faces and punch to the guts of so many of its diverse visitors. Since Stone Mountain is not designated a national park, nor is it in the state park system, it seems to fall into a gray area of accountability.

It’s 2015, and not one—but four!—Confederate flags still fly at the base of Stone Mountain, once an official bastion of white supremacy, when the Second Era KKK declared it its 20th Century rebirth place 100 years ago this November. The State of Georgia bought the property from the Venable Family in 1958, and even condemned the land in order to nullify an easement that would’ve still allowed the hate group to hold meetings at the mountain. And yet, today thousands of people of every race, religion, culture, and creed from across the world climb Stone Mountain and visit Stone Mountain Park yearly, which is great cause for celebration. And it’s high time Georgia's government and the park's administrators publicly reconcile the park's past ties (and obviously still lingering) with a hate group and lower these flags for good. It’s time to admit that the flags are a slap in the faces and punch to the guts of so many of its diverse visitors. Since Stone Mountain is not designated a national park, nor is it in the state park system, it seems to fall into a gray area of accountability.  That said, someone did see fit just before the 1996 Olympics to remove the 13 flags of the Confederate States adorning the old reflecting pool at the mountain’s summit, so we know this wouldn’t be the first time Confederate flags were moved from the mountain.

That said, someone did see fit just before the 1996 Olympics to remove the 13 flags of the Confederate States adorning the old reflecting pool at the mountain’s summit, so we know this wouldn’t be the first time Confederate flags were moved from the mountain.

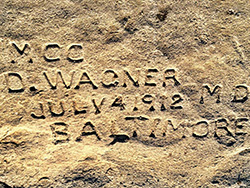

Stone Mountain Park should take a page from the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta and devote a wing of Confederate Hall to housing these remaining flags and addressing the jaw-dropping racism the mountain witnessed in its past through education and art. What an opportunity exists here to teach how it ever was that a hate group could take over and deface an innocent mountain for its nefarious purposes in the first place. Long before the Venable Family owned the land, as far back as tens of thousands of years ago, it was a sacred throughway of the Eastern Woodlands, Creeks, and Cherokees, and many ceremonies were held on the mountain, though little signs of the Native Americans was left in tact once building of the Confederate Memorial carving began. So many public schools take field trips to Stone Mountain throughout the school year. In addition to learning about geology and science, how about adding some civil and human rights lessons to the curriculum, maybe include a tour through historic Shermantown? Taking the flags down at the base of the mountain will offer long-overdue healing and help dispel tired stereotypes of the South as backwards, segregated, and racist.

To those of you that throw your hands up and cry, “You want to erase history! Well, what about The Cyclorama? Bet you want to get rid of that, too!” I remind you that The Cyclorama serves its educational purpose as a Civil War museum. Stone Mountain Park is not a museum, especially not the mountain itself. Yes, it has museums and the memorial carving on its premises, but is for the most part regarded by the people as a multicultural civic space, not unlike any public park, with many hiking trails enjoyed regularly by Metro Atlantans, immigrant communities in neighboring Clarkston, and scores of tourists. It creates such cognitive dissonance to see so much diversity and then see the Confederate flags whipping in the wind as I start up the walk-up trail.

To those of you that say that street names will be changed next, rest assured they thankfully already have been, long before this renewed debate about the Confederate flag. Many street names in Atlanta were in fact changed from those of Klansmen to prominent blacks and anti-segregationists in Atlanta's history (e.g. Ralph McGill Blvd. was once Forrest Ave., after Nathan Bedford Forrest, the first Grand Wizard of the KKK). Conversely, the street leading into Stone Mountain Park was changed to James B. Rivers Drive, after Stone Mountain’s first black Chief of Police, who served on the force from 1956-1995.

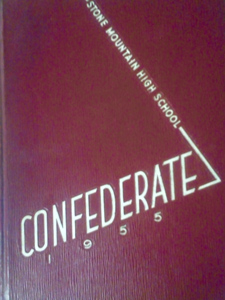

To those of you that cry out about your heritage, I ask, what kind of comfort and pride in one's past is really worth the great—and I mean monumental—discomfort of even one person? Why resist the virtues of unity and humanity—and Southern hospitality—all because someone with your DNA fought in a war to protect the institution of slavery? There’s a lot about our shared heritage for which we actually shouldn’t be proud, and this is why society as a whole must address past mistakes and do better next time—often a lot better. History, memorials, and symbols are everywhere—all worth learning about and reconsidering when societies' values shift in favor of the greater good of humanity. My high school yearbook at Stone Mountain High was once called The Confederate. I’m glad someone had the good sense to change it by the time I went to school there.

To those of you that cry out about your heritage, I ask, what kind of comfort and pride in one's past is really worth the great—and I mean monumental—discomfort of even one person? Why resist the virtues of unity and humanity—and Southern hospitality—all because someone with your DNA fought in a war to protect the institution of slavery? There’s a lot about our shared heritage for which we actually shouldn’t be proud, and this is why society as a whole must address past mistakes and do better next time—often a lot better. History, memorials, and symbols are everywhere—all worth learning about and reconsidering when societies' values shift in favor of the greater good of humanity. My high school yearbook at Stone Mountain High was once called The Confederate. I’m glad someone had the good sense to change it by the time I went to school there.