Less than two years after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. dreamed of freedom ringing from Stone Mountain in his 1963 “I Have A Dream” speech, another significant Atlantan (and frequent Athenian) surnamed King — “one of the most prominent negroes in this city” entered the narrative of Stone Mountain Park, though many still know little about Washington W. King, better known as W.W. King. But chances are they've walked or driven across one of the many iconic wooden covered bridges he built in Georgia, such as the covered bridge at Stone Mountain Park, Watson Mill Bridge, and the Euharlee Creek Covered Bridge. Many of his other bridges in Georgia didn't survive the passage of time and growing preference for iron and steel bridges.

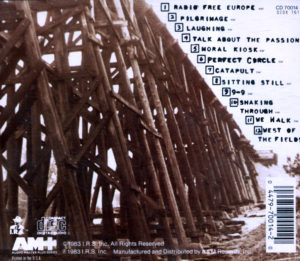

The more I've gotten to know W.W. King and his family through my research, the more I hope the quality and depth of the historic interpretation of King's impact in Georgia grows — particularly his decades of hard work over in Athens on so many bridges that are no longer standing, many which I will explore later in this essay. Perhaps after considering King's legacy in Clarke County and environs, you too may feel as strongly as I do that Athens should reclaim the bridge at Stone Mountain Park the very way the Watson-Brown Foundation brought the historic T.R.R. Cobb House back home from Stone Mountain Park in 2004 and restored it (more here on when it first moved to Stone Mountain). And the very way the community of Athens rallied successfully in the year 2000 to save the "Murmur Trestle" from demolition with the influential help of R.E.M. Though Athenians also voiced their desire to keep the historic College Avenue Bridge in Athens from being relocated to Stone Mountain over 50 years ago, the fate of King's bridge was not as lucky as that of the 1883 trestle, constructed for the Georgia Extension of the Georgia Railroad, and which is now a historic landmark situated near part of the still developing 39-mile Firefly Trail. TSPOLST (special transportation sales tax) funds are being secured at this time to "construct a crossing over Trail Creek at the Murmur Trestle," and, according to newly reelected Clarke County Commissioner Melissa Link, "the time to decide upon the fate of the trestle is soon," in terms of whether it can be historically restored or will have to be torn down and replaced, or partially preserved and built around. It appears to me that some of W.W. King's early bridge work in Athens, though likely no longer visible, may have been done near some points along the Firefly Trail, specifically at a junction or two with the Oconee River near downtown Athens, such as at the Broad St. Trailhead. Wouldn't it be something if the covered bridge he built in Athens back in 1891 could return home as a crossing at Trail Creek?

Stone Mountain Covered Bridge

Athens Weekly Banner, September, 09, 1890, “Across The Oconee: A Bridge To Be Built at the Foot of College Avenue."

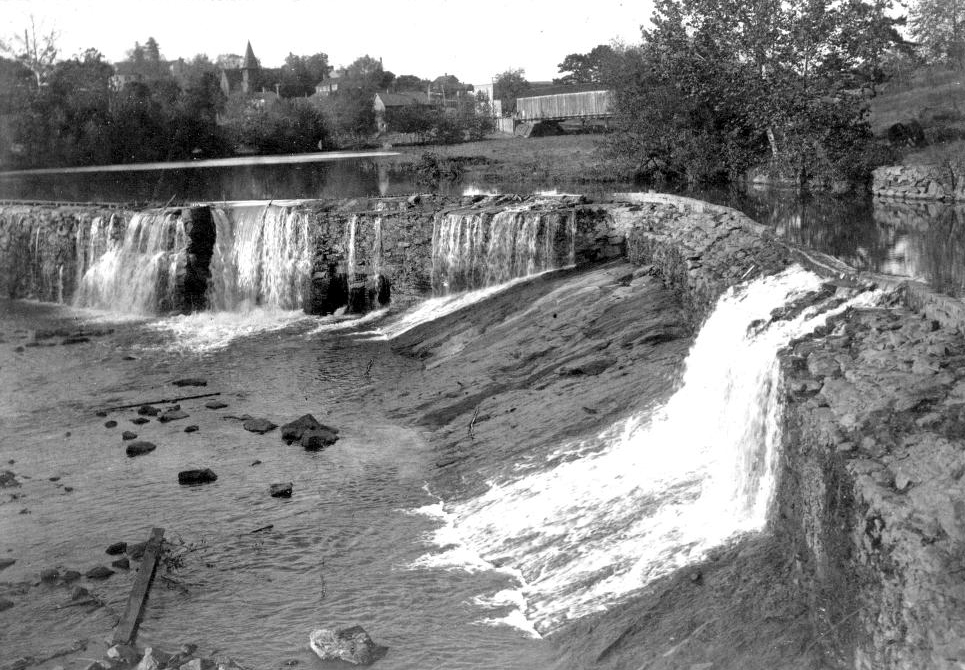

So, let's start with the historic, wooden covered bridge at Stone Mountain Park, which was relocated there 53 years ago from Athens, GA, in March 1965, despite strong community outcry at the time in Athens. According to Covered Bridges of Georgia (see Further Reading below), the Athens bridge was officially contracted to W.W. King in 1891 (though I found an 1890 newspaper item suggesting he would likely be the contractor for the new bridge and another from March 31, 1891 showing when the city commissioner was recorded as having secured the contract), and 73 years later, it was placed inside of a Confederate theme park nearing the eve of its opening on April 14, 1965. Newspaper articles from 1965 reported that the Town lattice bridge of pine had been damaged by flooding in July 1963, closed to traffic, then condemned. Therefore, in lieu of costly restoration, the bridge was donated by the Clarke County Commission for $1 to the Stone Mountain Memorial Association (SMMA), which soon after spent a total of $37,000 to transport, rebuild, and restore the bridge to specifications. The bridge had been separated into three 50-foot sections prior to being delivered to Stone Mountain Park by Walter Sullivan & Son, and was reconstructed upon piers of Stone Mountain granite, where it continues to function as an attraction connecting the park's mainland to the man-made, 17-acre Indian Island within Stone Mountain Lake, the man-made body of water from which, as of summer 2017, REI Boathouse operates. The trail from the covered bridge to the island is called King’s Trail, though that name is not in common use.

W.W. King's Athens Bridge Arriving at Stone Mountain

W.W. King's Athens Bridge Arriving at Stone Mountain

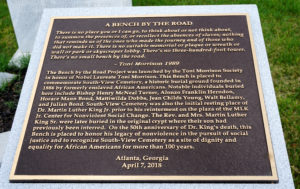

Marking History

Today, at the foot of the covered bridge in Stone Mountain Park, one finds an unofficial marker, which credits W.W. King with its construction and cites Athens as its provenance. But there is a lot more to this bridge's story — and W.W. King’s, as this was not his first or only wooden lattice bridge in Georgia, particularly not his first in Athens. This marker does not mention King's race or that his equally accomplished father, Horace King, born into slavery and later freed, was also a renowned “master covered bridge builder” all over Georgia and the Southeast, notably in LaGrange, GA and Columbus, GA, as well as in Carroll County, GA at the Moore's Bridge Park & Horace King Historic Site. (I'm curious if the same James D. Moore that donated the land where the Carroll Co. bridge was originally built was also the namesake for Moore's Ford Bridge in Monroe, GA, as it wouldn't be unthinkable for W.W. King's work to take him from Athens to nearby Monroe, and he did the High Shoals Factory bridge in 1888, which also crossed the Appalachee, between Oconee Co. and Morgan Co.— further research needed). Another notable, historic covered bridge by Horace King and his sons from 1870 can be seen at Callaway Resort & Gardens, where it was relocated in 1969 as a donation from the Troup County Commission of Roads and Revenue. Today the bridge is reportedly held in a private location and therefore not to be confused with the Butts Mill Farm covered bridge pitched by Pine Mountain as a wedding venue near Callaway.

Today, at the foot of the covered bridge in Stone Mountain Park, one finds an unofficial marker, which credits W.W. King with its construction and cites Athens as its provenance. But there is a lot more to this bridge's story — and W.W. King’s, as this was not his first or only wooden lattice bridge in Georgia, particularly not his first in Athens. This marker does not mention King's race or that his equally accomplished father, Horace King, born into slavery and later freed, was also a renowned “master covered bridge builder” all over Georgia and the Southeast, notably in LaGrange, GA and Columbus, GA, as well as in Carroll County, GA at the Moore's Bridge Park & Horace King Historic Site. (I'm curious if the same James D. Moore that donated the land where the Carroll Co. bridge was originally built was also the namesake for Moore's Ford Bridge in Monroe, GA, as it wouldn't be unthinkable for W.W. King's work to take him from Athens to nearby Monroe, and he did the High Shoals Factory bridge in 1888, which also crossed the Appalachee, between Oconee Co. and Morgan Co.— further research needed). Another notable, historic covered bridge by Horace King and his sons from 1870 can be seen at Callaway Resort & Gardens, where it was relocated in 1969 as a donation from the Troup County Commission of Roads and Revenue. Today the bridge is reportedly held in a private location and therefore not to be confused with the Butts Mill Farm covered bridge pitched by Pine Mountain as a wedding venue near Callaway.

Horace King's 1870 covered bridge at Callaway Gardens in its early days at the resort. Today it's held at a private location.

I don't know when the marker was put into the ground at Stone Mountain, but I wonder if mentioning W.W. King's race was deemed “inconvenient” at a venue celebrating the Confederacy as direct pushback against the Civil Rights Movement. Or was it just overlooked? During the 19th and early 20th Century, Washington King, his father, and his mother, Frances Gould Thomas, were variously listed in historic documents as "colored," "mulatto," or "Negro," as were his four siblings. Today W.W. King is usually described simply as "African-American" or "black," or his "non-whiteness" is only left to be inferred by phrases such as "the son of a freed slave." In all truth, their ethic background was likely more complex than "black" or "white," and NPR's "Code Switch" podcast about "race and identity, remixed" offers some good insights on our current society's labels and classifications for human beings of multiple racial backgrounds. Precisely because of the historical time and setting in which W.W. King and his family were living and working, the detail of their race truly does matter, especially as Horace King and his sons were among a select group of people of color enjoying their level of business success at that time, particularly in the South. It is also important to acknowledge that their work as bridge builders and contractors often cast them as foremen to laborers, a good deal of which were county convicts back when convict leasing was still legal — and in Horace King's time before Emancipation, many of the workmen he supervised on bridge projects were even enslaved men.

W.W. King's Athens bridge was placed inside a park with perhaps the world's largest Confederate monument, also the location of the 20th Century rebirth place of a white supremacist hate group, so in my opinion that makes his being a black man highly relevant. How inspiring it would've been all of these decades for so many people among the park's millions of visitors a year, especially Dekalb County students on field trips, to celebrate this. The spare website of the SMMA does refer to King an "African American bridge builder," but the 1961 date of relocation cited there is not accurate. Stone Mountain Park's website does not mention W.W. King and also lists the wrong date of the bridge's relocation from Athens. Whereas there are official Georgia Historical Society markers at two of his King's other remaining covered bridges in Georgia — Watson Mill Bridge (1885) at Watson Mill Bridge State Park in Comer, and Euharlee Creek Covered Bridge (1886) in Cartersville — the one at Stone Mountain doesn't appear to be officially sanctioned by a state or national historical authority. The marker at Watson Mill Bridge State Park does not mention W.W. King's race either, though the state park's website describes King as the "son of freed slave and famous covered-bridge builder Horace King." But I was delighted to discover that additional, thoughtful information about W.W. King’s race and family, even showing a photo of Horace King and his sons, which formed their own contracting company, are presented at the Euharlee Creek Covered Bridge site. The area is also home to George Washington Carver State Park which reopened in 2017 under new management, the Cartersville-Bartow County Convention & Visitors Bureau.

Kings of the Road

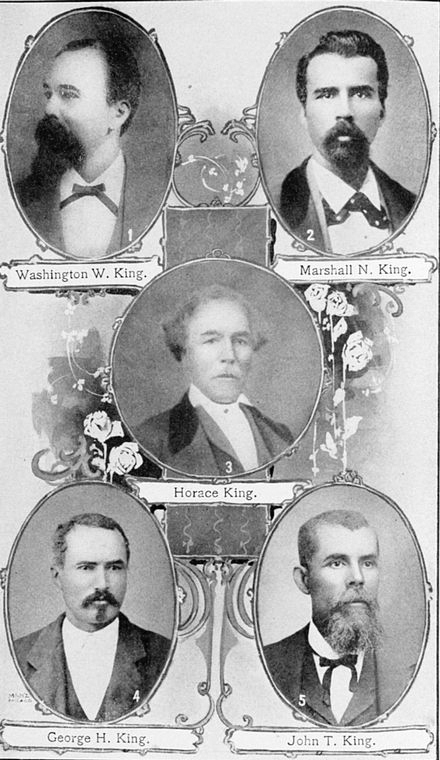

Horace King began receiving sorely overdue mainstream recognition just within the past twenty years, perhaps riding a long wave of covered bridge nostalgia in the 1990s, spurred in part by the runaway 1992 bestselling novel turned blockbuster 1995 movie, The Bridges of Madison County. He taught his four sons — Washington, Marshall, George, and John — his craft and even made sure to impart aspects of the family business to his daughter Annie Elizabeth. Horace King and his highly accomplished sons took on many projects together as King & Co., and later, the brothers incorporated as King Brothers Co., before W.W. King formed his own Bridge Co. Local historic newspapers chronicled the excellent quality of the Kings' work, though justifications about their race were often made. A May 13, 1883, LaGrange, GA newspaper story reprinted in the Atlanta-Constitution read, "King & Co. have put their variety works in motion and received their first building contract from the city—a neat pavilion for the cemetery. King is a colored man, a son of the famous Horace King, and inherits his sire's remarkable gifts in mechanism. He has a white man's principles and is highly respected. His patners [sic] are solid white citizens of means." It is not clear to which King son the quote refers, but that aspect of qualifying the work because they were "colored" often repeated in articles about W.W. King elsewhere. W.W. King, himself now long due for wider recognition, would also one day teach his son, Ernest Ware King, the family trade. Since a fair deal more has been written about Horace King, such as the 2004 book Bridging Deep South Rivers (see Further Reading below), my primary focus of this piece is to shine more light on the work of his first-born son, Washington.

Washington W. King was born free in Girard, Alabama on January 22, 1843, to Horace King and Frances Gould Thomas, a free woman who died at age 39, when Washington was 21 years old. Before moving to Atlanta, not long after the completion of Watson Mill Bridge in 1885 — the same year his father died on May 28, 1885 — W.W. King lived in Athens and put in decades of work there, primarily on the city’s bridges, which were a focus and major point of pride. Many wooden bridges were constantly being built, repaired, extended or rebuilt, in the Athens area in the 19th Century, seemingly every time heavy rains caused the rivers to flood, damaging main bridges and footbridges, and even completely carrying them away sometimes. Bridge workers, as well as the attendant county convict labor, certainly stayed busy, even more so when their skills intersected with the booming construction of so many new railroad lines. W.W. King appears to have been a contractor trusted above many others in 19th Century Athens, even on the rare occasion when his bid was slightly higher.

Georgia Swift King, Atlanta University Portrait, 1900. Josephine Dibble Murphy Collection, Photographs/Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library

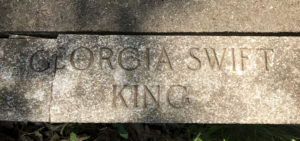

He also married Georgia Swift King in Clarke County in 1881. A year later, in 1882, their son Ernest Ware King was born, and a daughter, Annadel Chase King, soon followed in 1884. Though W.W. King moved back to Atlanta to helm his own company, Bridge Co., he continued to play a prominent role in building and superintending Athens' bridges (1908), and in surrounding area such as Gainesville, up until his untimely death in 1910.

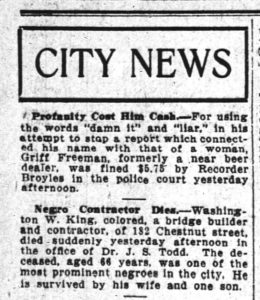

The Atlanta Constitution, 6/24/1910

King and his family made a home at 182 Chestnut Street (now James P. Brawley Drive), not far from where his wife, Georgia Swift King, was fast making a name for herself as a feminist scholar and social essayist at Atlanta University and an activist in the Christian temperance movement. She even stayed in touch with W. E. B. Du Bois after his tenure at Atlanta University, where she had participated in one or more of his conferences. She would outlive both her husband and children, all who died too young. Her husband's sudden death on June 23, 1910, at age 66, while at the office of the well-known Atlanta doctor, Dr. J. S. Todd, was announced the next day in the "City News" column of the Atlanta-Constitution, which was more ink than most "colored" citizens were usually granted upon dying at that time in history, though I have not yet found a funeral notice or death certificate for him, and this particular news item leaves out that his daughter, Annadel, was still living.

Annadel, a teacher like her mother, suffered a fatal heart attack on August 17, 1919, at age 35, according to her death certificate. Ernest, a bridge contractor after his father, kept an office in the historic Odd Fellows Building, now called 236 Atrium, in Sweet Auburn, and passed away on May 22, 1932, at age 50. Georgia Swift King passed away on May 16, 1944, at age 88.

Georgia Swift King In The News

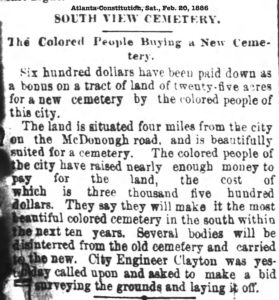

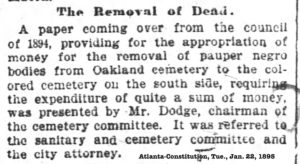

South-View Cemetery

Washington W. King & Family Burial Grounds

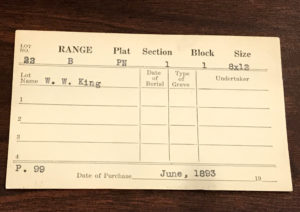

Washington W. King & Family Burial Grounds | Cemetery records indicate that W.W. King purchased the family cemetery lot at historic South-View Cemetery in June 1893. He, his wife, Georgia, two children, Ernest and Annadel, and mother-in-law, Felice, are interred here. Many primary structures and walls at South-View appear to be fashioned from Stone Mountain granite, as was quite customary in the Atlanta area in the late 19th Century, particularly in South-view's oldest section.

The eminent undertaker for Atlanta's black community at the time, David Tobias Howard (well-known as D.T. Howard), handled Annadel Chase King's and Ernest Ware King's funeral arrangements, and it's likely he also handled W.W. King's. Howard himself passed away in 1935 and is also buried in South-View (often written South View, Southview, and South Side Cemetery in old newspaper items or articles).

Further Reading

It's worth mentioning that two books about South-View Cemetery have been self-published in 2018, John Bayne's guidebook, Atlanta's South-View Cemetery (lulu.com; January 19, 2018), and D L Henderson's South-View: An African American City of the Dead (Carrelspin Press; March 25, 2018). Washington W. King and his wife, Georgia Swift King, are mentioned briefly on page 221 of Henderson's book. As well, one can read more about Horace King in Bridging Deep South Rivers: The Life and Legend of Horace King by John Lupold and Thomas French, Jr. (UGA Press; Aug. 31, 2004). The year before, Thomas French, Jr. and Edward L. French self-published the paperback edition of Covered Bridges of Georgia (Frenco; 2003; paperback), an update to the original hardcover (Frenco; 1984; hardcover).

Bridging the Past

1881-1882 — Princeton Factory Bridge Extension

"Athens has as many bridges across her river as the city of Cincinnati and two more than Louisville, Ky." — Athens Banner-Watchman, April 13, 1882

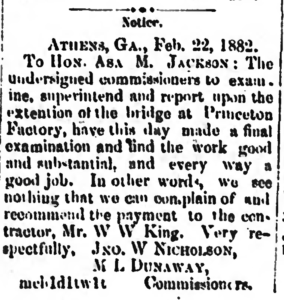

The same year that his son Earnest was born, W.W. King completed a bridge extension of the old Princeton Factory bridge, near the Middle Oconee River, for which his work was favorably assessed and payment was recommended by commissioner, M. L. Dunaway, in a newspaper notice, dated February 22, 1882, placed by Clarke County Commissioner. A “Notice To Bridge Builders” announcing the Princeton Factory project, and other bridge projects, ran for several weeks in the Athens Weekly Banner, such as this one in the June 1, 1881 edition.

1881-1883 — The Georgia Extension / Georgia Road / Georgia Branch / Georgia Branch Extension

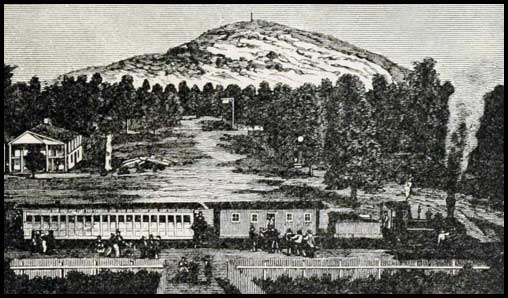

Georgia Railroad at Stone Mountain.

“Every train is bringing stone for culverts, and work on them will begin at once. The granite for this purpose comes from Stone Mountain.” —Athens Banner-Watchman, 4/13/1882

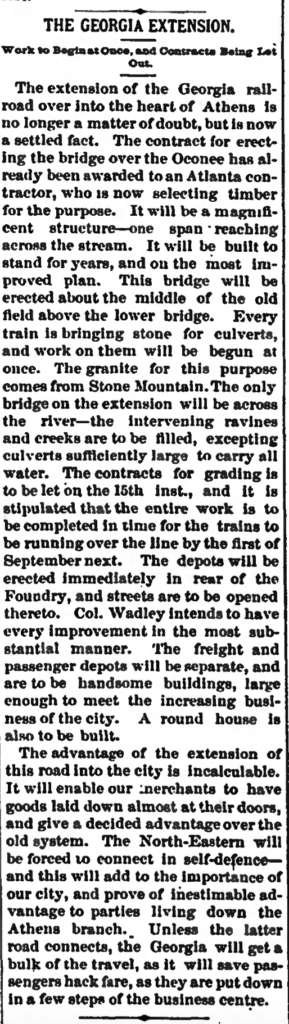

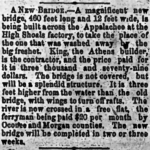

An early mention of “The Georgia Branch Extension” is included in a November 8, 1881 article about surveyors trying to determine the best and cheapest location for additional rail lines into the city. The short update concludes that “a long high trestle will have to be built to reach the city. It will be about half a mile long," which of course made me think of the trestle pictured on the back of R.E.M.'s 1983 album, Murmur. Another update on “The Georgia Extension,” on April 13, 1882, reported that “the contract for erecting the bridge over the Oconee has already been awarded to an Atlanta contractor, who is now selecting timber for the purpose.” It goes on to note that “every train is bringing stone for culverts, and work on them will begin at once. The granite for this purpose comes from Stone Mountain.” According to additional newspaper updates, the Georgia Railroad contractor for the project — though perhaps not the contractor for the wooden bridge itself? — was the firm of Rice & Coleman. Later reports reveal that much ado was also made in the press about Rice & Coleman utilizing the fairly new technology of the Ingersoll steam drill, as well as dynamite, to blast large quantities of rock in extending the railroad in Athens. “We learn that it cost $130,000 to extend the Georgia road over into the city—a distance of a mile and an eighth. The depot alone cost $9000. The contractors for the grading cleared nearly $10,000 on the job, after paying for all damages done by the blasters.”

Again, it bears explaining that the Georgia Rail road contractors, Rice & Coleman, employed many workmen on this project to extend the Georgia Railroad, many which may've been among a convict labor force. It would interesting to determine just who comprised their work crew. The issue of leasing convict labor over employing free labor was very contentious at this time, not just in Athens, but also at the quarry at Stone Mountain. Eventually it was resolved by most city governments to abolish the practice of convict leasing but still allow for convicts to work on public projects. A May 20, 1884 item in the Athens Banner-Watchman, offered an update on Clarke County's bridges, reporting that "a great deal of public work is being done by the county convicts, at considerable saving to the tax-payers[sic]." A snarky January 27, 1886 editorial comment from the Athens Daily Banner Watchman read, "It seems that convicts do not have a great deal to say against convict labor, though it is believed that most of them would rather be entertained in elegant leisure at the expense of the industrious people, than to help along with the public works."

1885 — Watson Mill Bridge

W.W. King was contracted to build the historic Watson Mill Bridge, which is the centerpiece of Watson Mill Bridge State Park in the city of Comer within Madison County. (Edited to add: The bridge was hit by a drunk driver in February 2019 but reopened).

1888 — High Shoals Factory Bridge

Though his first name or initials are not mentioned here, the sentence, "King, the Athens builder, is the contractor," sure leads me to believe he built this bridge across the Appalachee between Oconee County and Morgan County. Another bridge in this same location had been swept away by floodwaters the year before in 1887. And in 1902, King's wooden bridge at High Shoals—where Morgan, Oconee, and Walton counties intersect at the Appalachee River—would be replaced with an iron one. Iron and steel bridges would become the norm in years ahead and themselves were prone to washing right off their foundations in torrential, rushing waters. Again, I keep thinking of Moore's Ford Bridge over the Appalachee, which connected Walton Co. and Oconee Co., and wondering if W.W. King or King Brothers Co. might have ever constructed a wooden bridge there in decades prior to the gruesome 1946 lynching of five people near Moore's Ford Bridge (so far I've traced an 1874 covered bridge in the area but it may not correspond) — considered by some to be Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s first civil rights project while still a student at Morehouse College.

1890-1891 — College Avenue Bridge / Oconee Bridge / Effie's Bridge

Athens Weekly Banner, 11/25/1890, “The New Bridge." W.W. King would be contracted to build this bridge.

In its first home in Athens, the Stone Mountain Covered Bridge was variously known among townspeople, city officials, and journalists as the College Avenue Bridge, Oconee Bridge, and Effie’s Bridge, for its proximity to College Avenue, the Oconee River, and Effie's, a nearby row of brothel houses run by Miss Effie T. Matthews (1888-1966) of 175 Elm Street (also listed in census reports and city directories as Barrett St. in different years). More on Effie herself later, but her "lewd house," Effie's, which eventually multiplied into a row of four homes (none of which she owned), was officially shutdown and condemned in 1974 and burned down in 1977, despite (or perhaps because of?) campaigns to “Bring Effie’s Back” and casual talk of erecting a historic marker at the site of the devil-be-damned Athens landmark. It would hardly surprise me if removing W.W. King's "kissing bridge" near Effie's was somehow strangely connected to ridding Athens of every last link to the political scandal that Effie's posed to the city for decades. After all, prior to the bridge's relocation, Athens was embroiled in a high-profile vice investigation by the Clarke County grand jury in 1960, and then Mayor Ralph Snow went on record adamantly insisting he refused a $20,000-a-year bribe to look the other way and allow the organized prostitution to continue in Athens. Effie died in 1966, and her outstanding vice case, long postponed in 1960 because of a "serious heart ailment," was posthumously dismissed. Therefore, perhaps keeping "Effie's Bridge" in Athens may well have been in conflict with any powers that be which wished for Effie's legend, and any secrets surrounding her clientele or protectors, to be buried with Madame Effie over at Oconee Hills Cemetery. Though maybe a coincidence, the name "Effie's" does still sort of live on in Athens in the name of a local burlesque group, Effie's Club Follies.

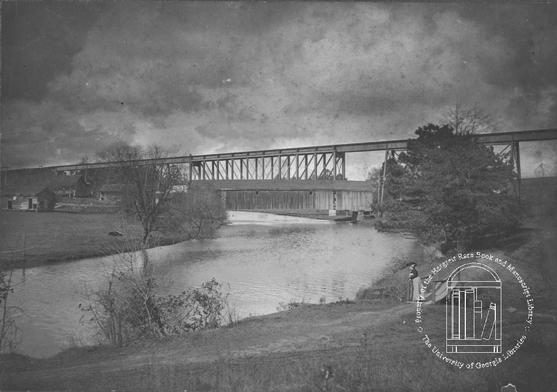

Athens, Oconee River (showing covered bridge) 1956; David Lewis Earnest photographic collection, circa 1900-1950s. MS 1590. Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, The University of Georgia Libraries.

1893-1894 — Check Factory Bridge / Middle Bridge / Broad Street Bridge / North Oconee Street Bridge

“The framing for the middle bridge has all been completed, and yesterday the workmen commenced putting it up. The completion of this bridge will be a great convenience to many of our people.” — January 16, 1894, Athens Weekly Banner

W.W. King was contracted to build the “Middle Bridge” over the North Oconee River near the historic Check Factory. Like so many of the bridges in the area, this particular bridge came to be known by many names, some official and others more like nicknames derived from their location in relation to town or to the river. So, "Middle Bridge" was often called Broad Street Bridge and Check Factory Bridge, and was, in general terms, referred to as North Oconee Bridge — NOT to be confused with this North Oconee River Bridge, also known as the Georgia, Carolina, and Northern Bridge shown below, which was contracted to A.L. and C.J. Houser of Anniston, AL, with Edge Moore Iron Co. of Wilmington, DE handling the truss decking, according to this April 28, 1891 Athens Banner Weekly article.

In 1909, the Broad Street Bridge was deemed removed due to irreparable river damage, according to April 30, 1909 report in the Athens Banner.

1893 — Hurricane Shoals Covered Bridge

Also in 1893, the Jackson Herald reported that a "Mr. King" was placing a bridge in the Jefferson, GA area at Hurricane Shoals in what is today known as Hurricane Shoals Park. I can only surmise this was Washington King, who was such an active bridge builder in the vicinity and, at that, one specializing in the Town lattice style of covered bridges. Therefore, the history recounted on the Hurricane Shoals Park's website, of this replica bridge that unfortunately was reported to have burned in 1972, should perhaps be reexamined to include King's contribution. Wooden bridges were so often requiring maintenance and repair back in the day, primarily owing to storms and flooding, but this bridge was certainly considered a major point of pride for the town around the time King was involved [Jackson Herald; 1-19-1893].

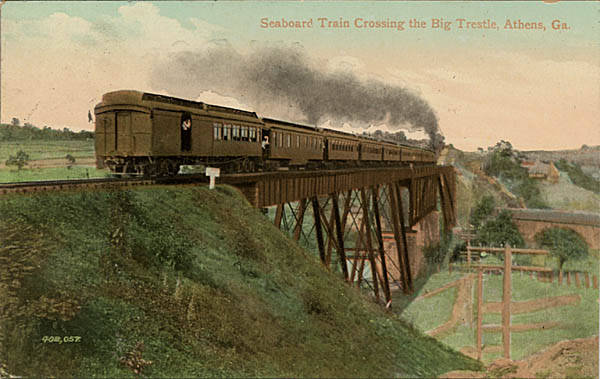

1889-1893 — Georgia, Carolina, and Northern Railroad / Seabord Air Lines

Another "magic road," the Georgia, Carolina, and Northern line (later consolidated with other lines and thereafter known as Seabord Air Lines, then simply as Seabord) would be built within the immediate years following the completion of the Georgia Railroad Extension, with G.C. & N. even moving their headquarters to Athens in October 1891. The April 25, 1892 edition of the Athens Weekly Banner reported the first regular connection to from Athens to Atlanta: "Atlanta, April 25 — The first regular train over the Georgia, Carolina, and Northern road reached Atlanta Sunday morning at 9 o'clock and made the run to Atlanta on time.” A more comprehensive timeline of the G.C.& N. will be added here soon.

1900-1901 — Gainesville (Hall & Forsyth) / Brown's Bridge

Prominent bridge builder W.W. King constructed numerous bridges in Gainesville, GA and the surrounding counties in what would later be heavily developed into the Lake Lanier Islands and Buford Dam. Lula Bridge is said to be located on private property in Gainesville. Brown's Bridge was removed in the 1950s when a "new Brown's Bridge," to be steel-trussed, was to be built, and I wonder if King's "old Brown's Bridge" was actually relocated elsewhere in the area, as there is no record of its destruction, whereas photo documentation exists of the destruction of nearby Keith's Bridge, first constructed in 1898.

Brown's Bridge

Speculations — Settendown Creek Bridge/ Frogtown/ Poole's Mill Covered Bridge

While researching the area's waterways and bridges, I was drawn to an old covered wooden bridge over Settendown Creek in the former Frogtown, GA area once inhabited by Cherokee Chief James Vann and his descendants, before Chief Vann's murder in 1809 and the later expulsion of area Native Americans via the Trail of Tears. At that time, the bridge was a simple, uncovered construction. Later it was often just referred to as Settendown, Settingdown, Sittingdown, Setting Down, Burnt Bridge, and, only in more recent decades, as Poole's Mill Covered Bridge. And, a few years after the bridge was highlighted in the 1968 feature in the Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine, the Georgia Conservancy took notice and urged for its preservation in 1972, even suggesting it could provide an anchor for a future park (after all, in a 1971 article, Stone Mountain Park and Callaway Gardens were among contemporary examples of parks incorporating historic covered bridges as attractions). Based on my research, something doesn't sit right about the history written on the historic marker for Poole's Mill Covered Bridge at Poole's Mill Bridge Park in Cumming/Ballground, GA in Forsyth. The information just seems incorrect or possibly even to be a composite of several bits of history of the original Settendown Bridge near Chief Vann's former land and possibly even borrows from the history of Brown's Bridge, which Washington King built in 1901 to replace the previous one there lost in an 1899 cyclone. So far I have yet to find information for a Chief Welch or a Bud Gentry and there's scant information about Poole, but it is well-established that Washington King was the most well-known for the Town Lattice style, even if it was a patented plan that another builder could've attempted. So many of the remaining Native American structures at the old Vann property were relocated to or reconstructed at New Echota. Perhaps the covered bridge shown in the above 1968 article was left and used inside Poole's Mill Bridge Park? A 1998 Atlanta Journal-Constitution story about Poole's Mill Covered Bridge makes mentions numerous erroneous holes in the structure, but might such holes possibly reflect damage incurred in moving the bridge from another location, such as from the old Frogtown area, or hey, what if it's even the "old Brown's Bridge" that was removed to make way for the Buford Dam and Lake Lanier? So many questions. [more to come]

Historic Postcard Collection GA Archives

Historic Postcard Collection GA Archives